The Great Cognitive Advance

On a per capita basis, the highly intelligent became ten times more numerous in England between 1000 and 1850

The Enlightenment (Wikicommons - TheErinCool). No longer voices crying in the wilderness, intellectuals became numerous enough to meet in coffeehouses, learned societies, and debating clubs.

Human populations have evolved over time, not only during prehistory but also well into recorded history. This evolution has affected a wide range of mental and behavioral traits: cognitive ability, time preference, propensity for violence, monotony avoidance, rule following, guilt proneness, and empathy, among others.

Such traits vary among human populations because different cultures have imposed different demands on mind and body. In general, the cultural environment will favor those who can better exploit its possibilities, just as the natural environment will. There has thus been a process of coevolution: we make culture, and it remakes us—by selecting those among us who survive to pass on their genes. This coevolution has proceeded along different trajectories in different populations.

One trajectory began during the Early Middle Ages on the northwestern fringe of Europe, where fishing peoples were learning how to use the North Sea for long-distance trade. From such inauspicious beginnings, they would achieve global dominance in a little over a thousand years:

In every respect, the 7th century marked a turning point: the old economic system was in its terminal phase and a new world was beginning to emerge. The accelerated decline of Mediterranean trade in the 7th century was linked by Belgian historian Henri Pirenne (1862-1935) to the Arab invasion; we have seen that the decline goes further back in time, even though Arab expansion in the 7th-8th centuries and Saracen piracy undoubtedly helped reduce trade even more …

But the great change was really the emergence of the North Sea as the main space of international trade with, around the mid-7th century, the birth of a network linking Frisia, England, Scandinavia and the Frankish world. (Chandelier, 2021, p. 192)

The failure of Rome

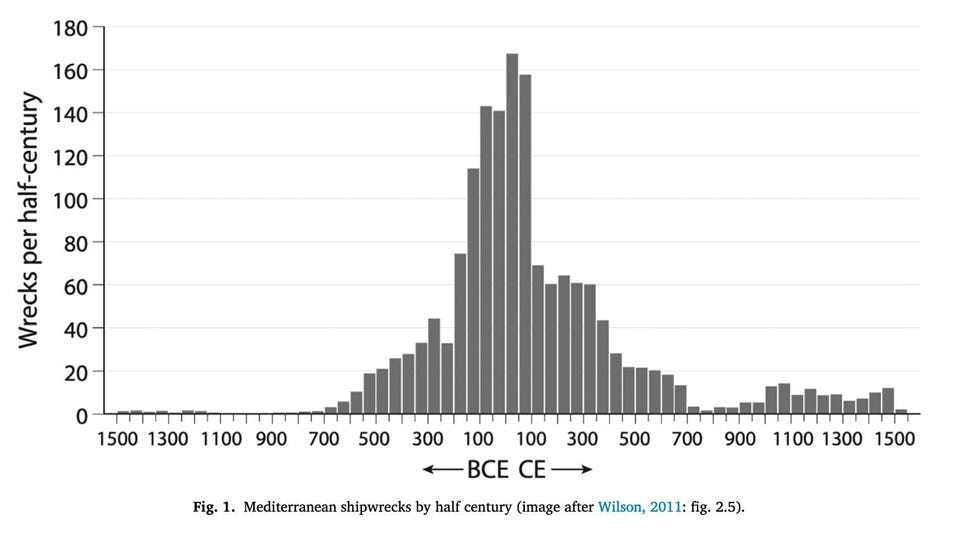

Why did the North Sea overtake the Mediterranean in international trade? Certainly, the latter region was disrupted by the Arab conquests of the Middle East and North Africa. But the decline in trade began much earlier. Shipwrecks on the bottom of the Mediterranean have been dated overwhelmingly to the time between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD. Silver mining in Spain and Cyprus likewise fell sharply after the 1st century, as shown by lead contamination of Greenland’s ice sheet (Terpstra, 2019).

The decline occurred not only before the Arab conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries but also before the barbarian invasions of the 4th and 5th and the Imperial Crisis of the 3rd. It thus happened when Roman imperial expansion was at its height. Yet this timing seems inconsistent with modern economic thinking: bigger markets should create economies of scale, as well as a better match between supply and demand. So what caused things to go wrong?

Familialism, cronyism, and nepotism

First, there was the low level of social trust. People trusted only their close friends and relatives, keeping everyone else at arm’s length. As a result, economic activity was bottled up within family networks, with the exception of physical marketplaces—where buyer and seller could meet face to face. Because the market principle remained trapped within small pockets of space and time, it could not generalize to all transactions in Roman society. An economy of markets never evolved into a true market economy.

In sum, the Pax Romana opened up a large space for peaceful exchange of goods and services. Economic activity did increase but remained largely confined within the small high-trust environments of family businesses. Once that source of economic activity had been tapped out, there remained little scope for further growth.

Deterioration of physical health

Familialism, cronyism, and nepotism may explain why the Roman economy grew only to a certain point. But the ensuing decline had at least two other causes.

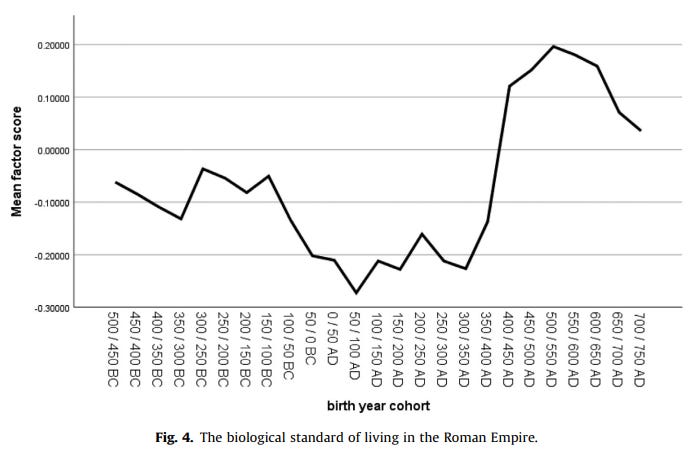

One was a deterioration of physical health, as indicated by the length of long bones belonging to over 10,000 adult men and women born between 500 BC and 750 AD. The data show a steady decrease from the 2nd century BC, reaching a low point in the second half of the 1st century AD, followed by a slow recovery and then a dramatic recovery from the 5th century (Jongman et al., 2019).

This trend may seem paradoxical, as it inversely correlates with the success of Imperial Rome: physical health deteriorated as the Empire expanded and then recovered as the Empire shrank. The study’s authors concluded that the Romans created not only an integrated Mediterranean economy but also “the first integrated disease regime”.

In health terms, however, the consequences were not necessarily that favourable. Roman cities had become the focal point of viruses and bacteria that all vectored in on them, to find a densely packed population. Historically, a declining biological standard of living under conditions of economic development and increasing economic integration is not unique, of course. (Jongman et al., 2019)

Physical health of adults in the Roman Empire, as indicated by skeletal data (Jongman et al., 2019, Figure 4)

Cognitive decline

The other cause was a decrease in average cognitive ability. Fewer people could master the skills of numeracy, literacy, and budgeting that are so essential to economic activity.

This decline was driven by an uncoupling of reproductive success from economic success. The wealthy were no longer using their wealth to bring children into the world. A rich man might prefer to leave his wife for a younger woman of low social status, often adopting her children. Or he might never marry.

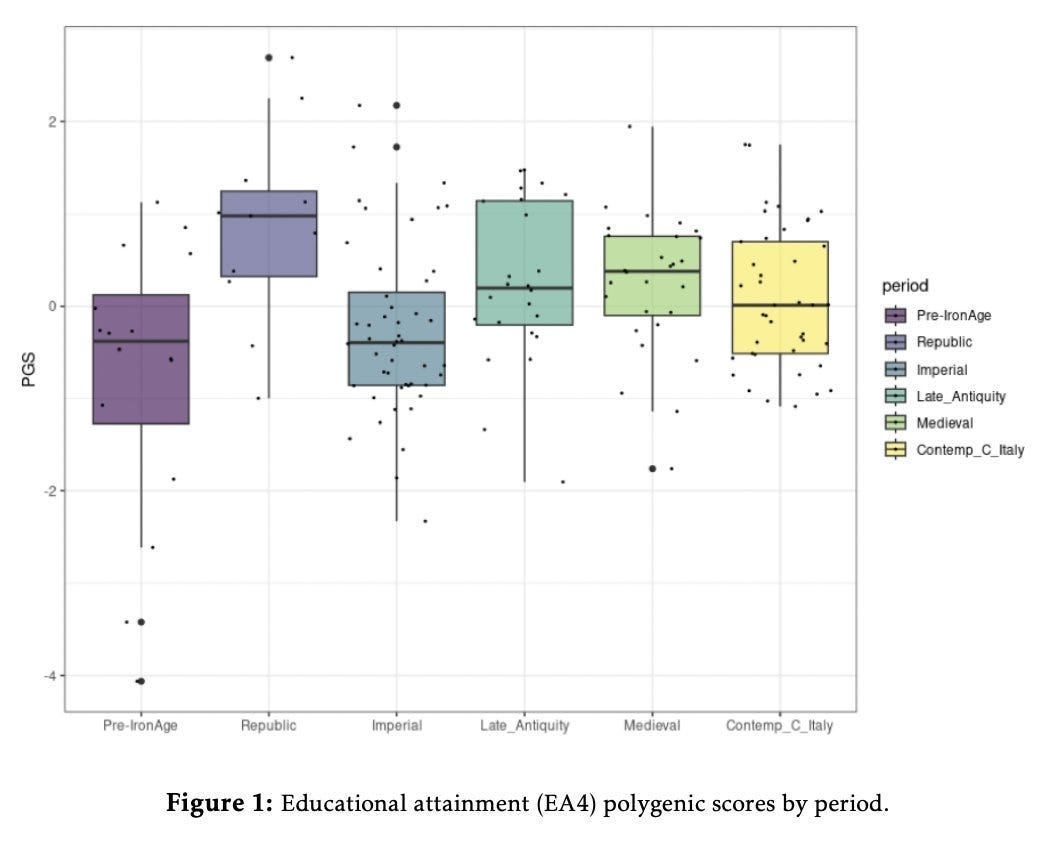

The resulting fall in cognitive ability can be seen in DNA retrieved from human remains in central Italy. People who lived in the Imperial Era had, on average, fewer alleles associated with high cognitive ability than those who lived in the Republican Era (Frost, 2024b; Piffer et al., 2023).

Rise, fall, and renewed rise of mean cognitive ability in central Italy. During the Imperial Era, the Romans lost all of the cognitive gains they had made previously since prehistoric times (Piffer et al, 2023, Figure 1)

We can chart this cognitive decline because of scientific advances in two areas: 1) retrieval of DNA from human remains; and 2) identification of alleles associated with educational attainment (which correlates highly with cognitive ability). While we have not identified enough of these alleles to estimate the intelligence of one individual, we can now reliably estimate the average intelligence of a sample of individuals.

Civilizational decline

As average cognitive ability decreased, so did its manifestations in daily life. The Romans still excelled at directing large numbers of people, often slaves. But they were not so good at innovation. Their medieval successors took much less time to find better ways of doing things:

Unseen in Roman society were the humble wheelbarrow and stirrup, which would not appear until the Middle Ages. Apart from mechanical clocks, medieval Europe invented heavy ploughs, spectacles, windmills, iron-casting, firearms and paper. The first half of the fifteenth century would add the printing press. Well before that time, medieval texts had been published in codex form, a massive improvement on the unwieldly book scroll of Roman antiquity. Along with better carriers of written information, the Middle Ages adopted a consistent system of graphic symbols, greatly facilitating the readability of the Latin script. Improved ship design in the thirteenth century allowed Mediterranean sailing year-round, unlike in Roman times when travel largely ceased during the winter months. … [T]he maritime shippers of the Middle Ages rejected heavy, breakable ceramic vessels as transport containers. Instead, they adopted the more practical wooden barrel, which had “a better volume to weight ratio, more efficient stacking capability, and greater maneuverability.” (Terpstra, 2019)

The success of northwest Europe

How it began

In the 7th century, a new space for trade opened up around the North Sea (Melleno, 2014). These traders were unlike those around the Mediterranean, for whom markets were merely marketplaces—small islands of exchange beyond which people produced for family, kin, or lord. The North Sea traders were the first to break free from an economic model where the individual is embedded in static, long-lasting relationships based on rank, kinship, and locality.

In this, they had an inherent advantage. The North Sea and Baltic peoples are particularly prone to certain mental and behavioral tendencies that, for over a millennium, have prevailed north and west of a line running from Trieste to St. Petersburg, i.e., the “Hajnal line.” These are tendencies toward individualism, the nuclear family, late marriage, and solitary living, as well as a greater willingness to trust strangers and form bonds of impersonal prosociality (Frost, 2025).

Northwest Europeans thus offered the best behavioral conditions for the emergence of a market economy, once this possibility arose. They were best able to expand economic relations beyond the limits of the local kin group—in fact, potentially beyond the limits of any group, no matter how large (Frost, 2020).

The same behavioral conditions would facilitate not only the expansion of the market economy but also that of the State and the Church. Indeed, all three institutions similarly expanded from the 11th century onward. And all three would create a new web of relations that had little to do with kinship, except metaphorically: “brothers and sisters in Christ,” “enfants de la patrie,” etc.

There was a synergy between these parallel expansions. Growth of the market economy was assisted by a State-Church consensus on the need to execute violent males so that law-abiding people could live in peace. By the Late Middle Ages, courts were condemning to death between 0.5 and 1% of all men in each generation, with perhaps just as many dying at the scene of the crime or in prison while awaiting trial. The pool of violent men dried up until most murders occurred under conditions of jealousy, intoxication, or extreme stress. As a result, the homicide rate fell from 20–40 homicides per 100,000 in the Late Middle Ages to 0.5–1 per 100,000 in the mid-20th century (Frost, 2023; Frost & Harpending, 2015).

A person could now get ahead in life through trade and work, rather than theft and plunder. The creation of a pacified environment thus favored the success of those who possessed market-oriented skills—not only literacy, numeracy, and budgeting but also initiative and a belief that one could shape one’s own future. Such people would form the emerging middle class.

The great cognitive advance

Beginning in the 11th century, the English middle class enjoyed a higher rate of natural increase than the lower class, which failed to replace itself demographically. With each generation, the lower class was gradually replaced by downwardly mobile individuals from middle-class families.

Initially, it was the tail trying to wag the dog: the middle class was too small to have much impact on the entire gene pool. By late medieval times, however, it had become sufficiently large to have an impact. Historical economist Gregory Clark has argued that English society now became increasingly middle class, both mentally and behaviorally. "Thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work were becoming values for communities that previously had been spendthrift, impulsive, violent, and leisure loving” (Clark, 2007; Clark, 2009; Clark, 2023; Frost, 2022c).

Sociologist Georg Oesterdiekhoff has argued for a similar evolution across Western Europe as a whole. He views this evolution in terms of Jean Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, i.e., more and more people could go beyond preoperational thinking (egocentrism, anthropomorphism, animism) and achieve operational thinking (ability to understand probability, cause and effect, and another person’s perspective) (Oesterdiekhoff, 2023; Rindermann, 2018, pp. 49, 86-87).

The earlier way of thinking is described by psychologist Heiner Rindermann:

There were trials against animals up to the sixteenth century, e.g. rats were ordered to appear in court for having eaten major parts of the harvest. Celestial bodies were seen as conscious beings that could be communicated with and which influenced people’s lives. (Rindermann, 2018, p. 87)

DNA studies

We can now verify this model of recent Western European evolution by comparing genomes from different time periods. There have been two such studies recently.

In the first one, present-day genomes were compared with genomes from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages (n=467). The comparison showed a substantial rise in average cognitive ability over time—between one third and one half of a standard deviation (Frost, 2024a; Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024).

The actual rise may have been even larger, since it is imperfectly measured by a comparison between medieval and present-day genomes. At one end of the timeline, according to Gregory Clark, cognitive ability had already begun to rise during the Middle Ages. At the other, it may have peaked in the Victorian Era and then declined thereafter (Frost, 2022d). Also, the rise in cognitive ability may have begun earlier in some parts of Western Europe than in others.

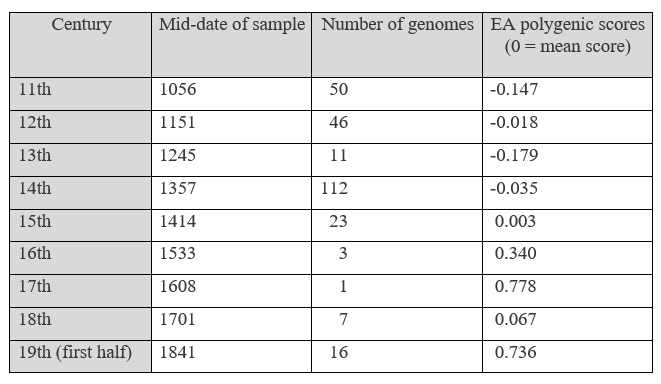

To address these limitations, a second study was conducted with genomes from one region of England (Cambridge and surrounding area, n=269). The genomes are from the 11th to 19th centuries (Piffer & Connor, 2025).

Genomes by century and mean EA polygenic score by century (Piffer & Connor, 2025. Table 1)

For some centuries, notably the 16th to the 18th, we have too few genomes for a century-by-century analysis. But the overall trend is clear: a rapid increase in mean cognitive ability from the 1300s onward.

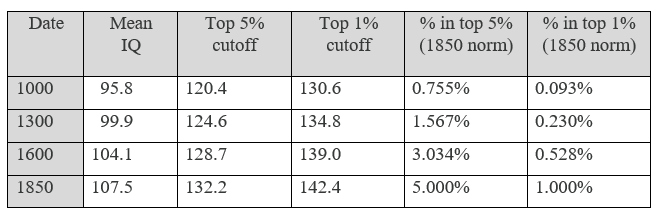

Particularly impressive is the increase in the "smart fraction": the top 1% in 1850 was as smart as the top 0.1% in the year 1000.

Estimated percentage of the population in the top 5% and top 1% as defined by 1850 norms and using the linear regression for the whole period (Piffer & Connor, 2025, Table 3). EA scores have been converted into IQ scores for ease of interpretation.

Thus, on a per capita basis, the last millennium saw a massive increase in the number and proportion of highly intelligent people. No longer voices crying in the wilderness, there were increasingly enough of them to meet in coffeehouses, learned societies, and debating clubs. This synergy would give rise to the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, ultimately energizing all areas of life—not only the sciences but also literature, music, and the arts (de Courson et al., 2023).

The authors of the above studies—Davide Piffer, Gregory Connor, and Emil Kirkegaard—intend to pursue this research. In particular, they hope to answer the following questions:

Did cognitive evolution proceed at the same pace from the 11th to 19th centuries? The current data suggest that it was sluggish at first and then took off sometime in the 1300s.

Did the take-off occur in one part of Western Europe and then spread elsewhere? One candidate region would be England and Holland, which began their economic take-off in the 1300s (Frost, 2022a). Another would be northern Italy during the Renaissance (Rindermann, 2018, p. 133, 141-142, 259-260).

When did cognitive evolution come to a halt? Did it peak in the late 19th century and decline thereafter with the rise of industrial capitalism and the severance of the link between economic and reproductive success? (Frost, 2022d).

Was there a parallel evolution of other mental and behavioral traits? For example: time preference, propensity for violence, impulse control, guilt proneness, empathy, etc. Did this parallel evolution create a positive feedback loop? i.e., high frequency of “middle-class” traits → growth of the market economy → growth of the middle class → higher frequency of “middle-class” traits.

Did cognitive evolution include alleles that are cognitively beneficial as heterozygotes but deleterious as homozygotes? One example might be alleles for autism, which became more frequent in England with rising cognitive ability (Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024). This sort of heterozygote advantage has already been noted in Ashkenazi Jews with respect to lysosomal storage diseases: Tay-Sachs (2 alleles); Gaucher's (5 alleles); Niemann-Pick; and Mucolipidosis Type IV. All of these alleles became frequent in the same period of time, the same population, and the same metabolic pathway—an indication of natural selection, and strong selection at that (Cochran et al., 2006; Diamond, 1994; Frost, 2022b). Such alleles attest to the rapidity and recentness of the rise in cognitive ability. There are still adverse side-effects because selection has not had enough time to work the bugs out. Evidently, these alleles account for only a fraction of the total rise in cognitive ability among Ashkenazi Jews.

To answer these questions with sufficient detail and clarity, we will need more genomic data from medieval/post-medieval times. Such data could also help us better understand the recent evolution of other genetically influenced traits.

References

Chandelier, J. (2021). L’Occident médiéval. D’Alaric à Léonard. 400-1450. Mondes anciens, Paris: Belin. https://www.belin-editeur.com/loccident-medieval

Clark, G. (2007). A Farewell to Alms. A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton University Press: Princeton. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691141282/a-farewell-to-alms

Clark, G. (2009). The domestication of man: the social implications of Darwin. ArtefaCToS, 2, 64-80. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277275046_The_Domestication_of_Man_The_Social_Implications_of_Darwin

Clark, G. (2023). The inheritance of social status: England, 1600 to 2022. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A., 120(27), e2300926120 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300926120

Cochran, G., Hardy, J., & Harpending, H. (2006). Natural history of Ashkenazi intelligence. Journal of Biosocial Science, 38(5), 659-693. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932005027069

de Courson, B., Thouzeau, V., & Baumard, N. (2023). Quantifying the scientific revolution. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 5, E19. https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2023.6

Diamond, J.M. (1994). Jewish Lysosomes. Nature, 368, 291-292. https://doi.org/10.1038/368291a0

Frost, P. (2010). The Roman State and genetic pacification. Evolutionary Psychology, 8(3), 376-389. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491000800306

Frost, P. (2020). The large society problem in Northwest Europe and East Asia. Advances in Anthropology, 10(3), 214-134. https://doi.org/10.4236/aa.2020.103012

Frost, P. (2022a). When did Europe pull ahead? And why? Peter Frost’s Newsletter. November 21.

Frost, P. (2022b). Ashkenazi Jews and recent cognitive evolution. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 5.

Frost, P. (2022c). Europeans and recent cognitive evolution. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 12. https://www.anthro1.net/p/europeans-and-recent-cognitive-evolution

Frost, P. (2022d). The Great Decline. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 20.

Frost, P. (2023). 1. Genetic pacification in Western Europe from late medieval to early modern times. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 19.

Frost, P. (2024a). Cognitive evolution in Europe: Two new studies. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, March 14. https://www.anthro1.net/p/cognitive-evolution-in-europe-two

Frost, P. (2024b). How Christianity rebooted cognitive evolution. Aporia Magazine, October 10.

Frost, P. (2025). Adapting to an environment of their making. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, February 25. https://www.anthro1.net/p/adapting-to-an-environment-of-their

Frost P., & Harpending, H. (2015). Western Europe, state formation, and genetic pacification. Evolutionary Psychology, 13(1), 230-243. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491501300114

Jongman, W. M., Jacobs, J.P. & Goldewijk, G.M.K. (2019). Health and wealth in the Roman Empire. Economics & Human Biology, 34, 138-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.01.005

Melleno, D. (2014). North Sea networks: trade and communication from the seventh to the tenth century. Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 45, 65-89. https://doi.org/10.1353/cjm.2014.0055

Oesterdiekhoff, G.W. (2012). Was pre-modern man a child? The quintessence of the psychometric and developmental approaches. Intelligence, 40, 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2012.05.005

Piffer, D., & Connor, G. (2025). Genomic Evidence for Clark's Theory of the British Industrial Revolution, preprint, ResearchGate, June. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392808200_Genomic_Evidence_for_Clark's_Theory_of_the_British_Industrial_Revolution

Piffer D, Dutton, E., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2023). Intelligence Trends in Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of Roman Polygenic Scores. OpenPsych. Published online July 21, 2023. https://doi.org/10.26775/OP.2023.07.21

Piffer, D., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2024). Evolutionary Trends of Polygenic Scores in European Populations from the Paleolithic to Modern Times. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 27(1), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2024.8

Rindermann, H. (2018). Cognitive Capitalism. Human Capital and the Wellbeing of Nations, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cognitive-capitalism/7C10B724756D97F00B7AF0515B800CC5

Terpstra, T. (2020). Roman technological progress in comparative context: The Roman Empire, Medieval Europe and Imperial China. Explorations in Economic History, 75, 101300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2019.101300

Unfortunately, the cocktail of traits that made Western civilization doesn't seem to constitute an evolutionarily stable strategy.

That cocktail created prosperity, which, coupled with empathy and egalitarianism, led to the welfare state, which in turn is dysgenic for almost all civilization-making traits.

Not only that, the Western man decided to extend the welfare state to the whole world, subsidizing the proliferation of masses that will not be able to sustain modern civilization or themselves once the global welfare state is gone. And in the final phase of suicidal empathy, he decided to import a sizable share of those Third World masses into his own home, turbocharging the decline.

Interesting article. A few small points.

1) Not sure why you identify the start in western England in 7th century. That area was a real economic backwater.

2) In the table, I notice that the IQ increase does not appear to start until the 16th century. This meshes well with when southeast England started commercializing. As you note, the tiny sample size is a problem, but there appears to be no clear trend before that time.

3) I think the city/states of Northern Italy is a more likely start for the trend as they were the first Commercial society after the Roman Empire.

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/how-medieval-northern-italy-transformed

4) You seem to be making two competing claims that contradict each other: the increase in IQ started long before the Roman Empire (which you go into more detail in the article below) and the increase started with rise of commercial cities in the early modern period. I am much more persuaded by the latter.

https://www.anthro1.net/p/when-did-northwest-europeans-become