The Great Decline

Regressive cognitive evolution in the West

Mrs. Hawkins and Family, 1818-20 (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

In the European world, cognitive evolution was driven by the middle class having more babies than everyone else. That baby boom ended in the late 19th century. There then ensued a decline in cognitive ability from one generation to the next.

From the Late Middle Ages onward, cognitive evolution was driven by the middle class having more babies than everyone else. They had the skills to identify and exploit opportunities in the expanding market economy, particularly skills like reading, writing, calculating, budgeting, and negotiating. In some countries, most of the population would end up being middle-class or having recent middle-class ancestors.

That baby boom began to run out of steam in the late nineteenth century. Household workshops, where family members did the work, gave way to factories, where it was done by employees. Instead of marrying earlier and having more children, a successful industrialist would hire more laborers. Factory capitalism thus severed the link between economic success and reproductive success.

Meanwhile, the middle-class lifestyle was imposing more and more socially defined needs: a big home, a summer cottage, a luxury car, a college education for the kids, and so on. Couples maintained that lifestyle by reducing the number of children they had.

That fertility decline led to a decline in mean cognitive ability, as shown by several lines of evidence: alleles associated with educational attainment; cranial volume; visual reaction time; and Piagetian tests.

Decline in alleles associated with educational attainment

Three studies have shown a decline in the population frequency of alleles associated with high educational attainment (EA polygenic score), specifically among European Americans, British people, and Icelanders.

European Americans

Beauchamp (2016) examined genomic data from Americans of European ancestry born between 1931 and 1953 (n=6,403 women and 5,419 men). The data came from the Health and Retirement Study, a representative study of Americans shortly before and during retirement.

For successive birth cohorts from 1931 to 1953, there was a decline in the frequency of alleles associated with high educational attainment. “[M]y results strongly suggest that genetic variants associated with EA have slowly been selected against.”

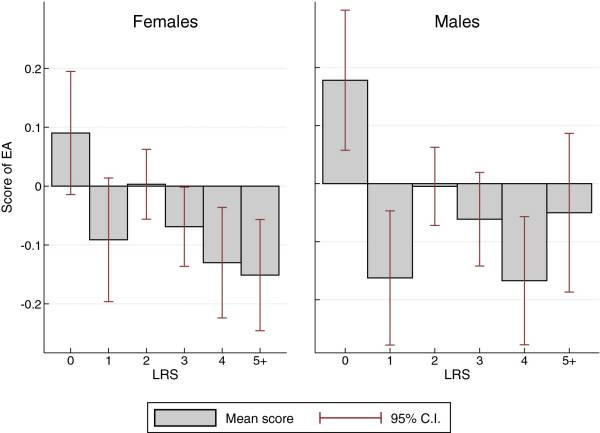

The selection was driven by differences in fertility: “individuals with high EA typically have children at a more advanced age, which may further reduce their fitness.” Men and women with no children had, on average, a significantly higher EA polygenic score than those with one or more.

Mean polygenic score as a function of lifetime reproductive success (LRS) for alleles associated with educational attainment (EA) (Beauchamp, 2016, Fig. 2)

British people

Hugh-Jones and Abdellaoui (2022) examined genomic data from two successive generations of British people of European origin, using the UK Biobank (n=409,629). The median birth year was unknown for the first generation and 1950 for the second.

Mean cognitive ability declined from the first generation to the second, particularly in lower-income groups. The authors also looked at alleles that influence non-cognitive traits. Those alleles indicate that the bulk of the population became not only less intelligent but also more obese and more prone to mental illness, specifically attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and neuroticism. On the other hand, they also became more prone to extraversion, especially men.

Icelanders

Kong et al. (2017) examined genomic data from Icelanders born between 1910 and 1990 (n=129,808). The data came from a genealogical database.

The authors found that the mean polygenic score “has been declining at a rate of ~0.010 standard units per decade,” where one unit equals one standard deviation. Moreover, because the polygenic score “only captures a fraction of the overall underlying genetic component the latter could be declining at a rate that is two to three times faster.”

The decline had two pauses: first in the 1950s and again in the 1970s. The first pause coincided with the postwar economic boom and a corresponding improvement in the ability of middle-class couples to start their families early in life. The second pause might reflect the passage in 1975 of a law to liberalize access to abortion in cases of rape, mental disability of the mother, and “difficult family situation” (Wikipedia, 2022)

The authors of the study concluded that the cognitive decline was due only in part to more intelligent Icelanders staying in school longer and postponing reproduction. Higher cognitive ability was reducing fertility independently of higher education, perhaps because of its association with the ability to plan ahead and foresee the costs of raising a family.

Mean polygenic score of Icelanders by year of birth for alleles associated with educational attainment (Kong et al., 2017, Fig. 2)

Criticisms of the above studies

Survivorship bias. The above studies may suffer from survivorship bias. People who live to an old age are generally smarter than those who do not (Gottfredson and Deary, 2004).

Beauchamp (2016) denies that survivorship bias explains his findings, saying that no important differences emerged when he compared the genotyped participants with the total sample of living and dead ones. Of the original participants, 85% were still alive in 2008 (the last year of genotyping), 69% were asked to be genotyped, and 59% consented to be genotyped.

Kong et al. (2017) acknowledge the risk of survivorship bias but see it as low for the last five cohorts born since 1940. It is especially low for the last two cohorts born during the 1970s and the 1980s. Those participants, like the others, were genotyped between 1998 and 2014, with a majority (68%) being genotyped before 2006 (Kong et al., 2017, p. E729).

Ascertainment bias. Hugh-Jones and Abdellaoui (2022) raise the possibility of ascertainment bias. They had no data on childless individuals from the first generation, their data being confined to the parents of the second generation. Were those childless individuals more intelligent or less intelligent on average? Another potential source of bias is the voluntary nature of contributions to the UK Biobank.

Excessive pessimism. Hugh-Jones and Abdellaoui. (2022) argue against excessive pessimism:

Many people would probably prefer to have high educational attainment, a low risk of ADHD and major depressive disorder, and a low risk of coronary artery disease, but natural selection is pushing against genes associated with these traits. Potentially, this could increase the health burden on modern populations, but that depends on effect sizes.

They go on to argue that the effect sizes are “small.” Beauchamp (2016) is similarly reassuring: “natural selection has thus been occurring in that population—albeit at a rate that pales in comparison with the rapid changes that have occurred in recent generations.”

Decline in cranial volume

Valge et al. (2019) examined the physical characteristics, educational attainment, and fertility of Estonians born between 1937 and 1962 (see also Hõrak and Valge, 2015). The data came from an earlier anthropometric study conducted between 1956 and 1969 (n=7,123 boys and 9,866 girls).

Estonian women with only primary education had 0.5 to 0.75 more children than those with tertiary education. The difference in reproductive success correlated with a difference in cranial volume: children with larger crania were more likely to go on to secondary or tertiary education, independently of sex, socioeconomic position, and rural vs urban origin. Thus, higher education reduced female fertility, probably by delaying marriage.

As for Estonian men, the most fertile ones had an average cranial volume, as well as greater height and strength. Perhaps surprisingly, female fertility correlated with having a more masculine body build, narrower hips, and shorter legs, apparently because such women are less selective and likelier to marry earlier: “If choosiness in women increases with desirability, this could lead to women with more feminine phenotypes engaging in a more time-consuming mate selection process, delaying their age of first birth, and thereby negatively affecting reproduction.”

Lengthening of visual reaction time

Silverman (2010) obtained visual reaction times from 14 studies published since 1941and compared them with visual reaction times from a study conducted by Francis Galton in the late nineteenth century.

With one exception, the post-1941 studies revealed visual reaction times longer than those conducted by Galton. Using the correlation between visual reaction time and g, Woodley et al. (2013) calculated a decline of 1.23 IQ points per decade, for a total of 14 points since Victorian times. That decline might be due, however, to a more representative sampling of the general population by later studies (hbd*chick, 2013).

On the other hand, the same lengthening of reaction time has been shown by Swedish, Scottish, and American participants, particularly those born since circa 1980. The IQ decline was likewise calculated to be 1.3 to 1.7 points per decade (Madison, 2014; Madison et al., 2016).

Lengthening of reaction time in Swedish, British, and American participants (Madison, 2014)

Falling scores on Piagetian tests

Flynn and Shayer (2018) examined the results of Piagetian tests in England and Wales from 1975-1976 to 2006-2007.

Test scores fell after 1993, at a time when conventional IQ test scores were still rising. In particular, the “smart fraction” shrank at a faster rate than did the fraction of students who were simply above average:

The Piagetian results are particularly ominous. Looming over all is their message that the pool of those who reach the top level of cognitive performance is being decimated: fewer and fewer people attain the formal level at which they can think in terms of abstractions and develop their capacity for deductive logic and systematic planning.

A Piagetian test differs from a conventional IQ test in that it is much more demanding. You cannot pass it by simply having a strong procedural memory, low exam anxiety, and good familiarity with likely questions and their correct answers.

And yet IQ scores were rising!

Mean IQ rose throughout the twentieth century. Flynn (1984) calculated a rise of 13.8 points between 1932 and 1978 among European Americans. When that increase, now called the Flynn effect, was charted from 1920 to 2013, it amounted to no less than 35 points (Pietschnig and Voracek, 2015).

The increase was not uniform over time. It can be broken down into five periods:

a small increase between 1909 and 1919 (0.80 points/decade)

a surge during the 1920s and early 1930s (7.2 points/decade)

a slower pace of growth between 1935 and 1947 (2.1 points/decade)

a faster one between 1948 and 1976 (3.0 points/decade)

a slower pace thereafter (2.3 points/decade)

The Flynn effect began in the core of the Western world and is now ending there. In fact, it has ended altogether in Norway and Sweden and has begun to reverse itself in Denmark and Finland (Pietschnig and Voracek, 2015).

The sharp rise in IQ over the past century is far from obvious to someone like myself who lived in that century and who knew people born as early as 1900. I also knew the old textbooks that they used and which our elementary school kept in a storeroom. If they had been less intelligent than my generation, how could they have understood those textbooks? How could they have handled the dense subject matter, the vocabulary, the detailed charts and figures, and the long and complex sentences?

Here are some questions from a Grade 8 exam given in 1912 to children in Bullitt County, Kentucky:

Find cost at 12½ cents per sq. yd. of kalsomining the walls of a room 20 ft. long, 16 ft. wide and 9 ft. high, deducting 1 door 8 ft. by 4 ft. 6 in. and 2 windows 5 ft. by 3 ft. 6 in. each.

A man sold a watch for $180 and lost 16 2/3%. What was the cost of the watch?

How many parts of speech are there? Define each.

What is a personal pronoun? Decline I.

Define longitude and latitude.

Tell what you know of the Gulf Stream.

Through what waters would a vessel pass in going from England through the Suez Canal to Manila?

Compare arteries and veins as to function. Where is the blood carried to be purified?

Define Cerebrum; Cerebellum.

Define the following forms of government: Democracy, Limited Monarchy, Absolute Monarchy, Republic. Give examples of each.

Name five county officers and the principal duties of each.

What is a copyright? Patent right?

Describe the Battle of Quebec.

Name the last battle of the Civil War; War of 1812; French and Indian War and the commanders in each battle. (Sieczkowksi, 2013)

The Flynn effect also implies that post-millennials are 10 points smarter than my generation. Again, that’s not my impression. Books and movies now have simpler plots and use a smaller vocabulary—a key component of verbal intelligence.

Are there real-world indications that we have become smarter on average? Howard (1999, 2001, 2005) cites four:

The prevalence of mild mental retardation has fallen in the US and elsewhere.

Chess players are reaching top performance at earlier ages.

More journal articles and patents are coming out each year.

According to high school teachers who have taught for over 20 years, “most reported perceiving that average general intelligence, ability to do school work, and literacy skills of school children had not risen since 1979 but most believed that children's practical ability had increased” (Howard, 2001).

The above evidence is debatable, as Howard himself acknowledges. Fewer children are being diagnosed as mentally retarded because that term has become stigmatized. Prenatal screening has also had an impact. As for chess, it’s a niche activity that tells us little about the general population. More journal articles are indeed being published each year, but the reason has more to do with pressure to “publish or perish.” Finally, teachers are not objective observers: they are part of a system that rewards certain views and penalizes others. If they reject that system, they probably won’t remain for twenty years.

I suspect we are indeed doing better on IQ tests simply because we’re spending more of our lives sitting in a classroom … and taking tests. In addition, IQ scores may have been inflated by the increase in test preparation during the late twentieth century, notably for the Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT).

Conclusion

Beginning in the eleventh century, the European world embarked on a trajectory of sustained cognitive evolution, due to the demographic expansion of the middle class (Frost, 2022). That trajectory ended in Victorian times and gave way to regressive cognitive evolution. We now have intergenerational polygenic studies from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Iceland. All three studies show a decline in the genetic component of cognitive ability during the twentieth century.

The decline can be traced to differences in fertility, specifically between the more educable and the less educable. “In all countries [Australia, United States, Norway, Sweden], however, education is negatively associated with childbearing across partnerships, and the differentials increased from the 1970s to the 2000s” (Thomson et al., 2014).

Those differences in fertility may explain the slowing down and reversal of the Flynn effect. Once the adult population had become fully proficient in test-taking, the Flynn effect ran into a wall and could no longer mask the real decline in cognitive ability.

Bratsberg and Rogeberg (2018) have shown that the reversal of the Flynn effect in Norway can be explained by “within-family variation.” In other words, mean IQ is declining among siblings who supposedly share the same genetic background. In Norway, however, siblings are increasingly half-siblings. Among Norwegian women with only two children, 13.4% have had them by more than one man. The figure rises to 24.9% among those with three children, 36.2% among those with four children, and 41.2% among those with five children (Thomson et al., 2014).

In Norway, children are increasingly born to divorced women who have entered into relationships with men of the lowest educational level:

At age 45, about 15 percent of all men in the 1960-62 cohort with a compulsory education had had children with more than one woman, compared to about 5 percent among men with a tertiary degree. If looking at fathers only (Figure 6), the pattern becomes even more pronounced. At the lowest educational level, 19.3 percent of those who had become fathers had children with more than one woman, compared to 6.1 percent of those at the highest educational level. (Lappegård et al., 2011)

The family unit is decomposing in Norway, as it is elsewhere in the West. The process began in the late nineteenth century, when the middle class ceased to translate economic success into reproductive success. There then ensued a fertility decline that would be reversed only during the postwar era, when the fruits of economic growth were widely distributed and when the culture was much more pro-family than it is today (Frost, 2019). The downward trend then resumed, to the point that the family is becoming little more than an administrative entity that can be repeatedly dissolved and reconstituted.

Are there steps we can take to reverse that trend? Yes. The first step, and the hardest one, is simply to acknowledge what is happening.

References

Beauchamp, J.P. (2016). Genetic evidence for natural selection in humans in the contemporary United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(28): 7774-7779. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1600398113

Bratsberg, B., and O. Rogeberg. (2018). Flynn effect and its reversal are both environmentally caused. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (26) 6674-6678. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1718793115

Flynn, J.R. (1984). The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932–1978. Psychological Bulletin 95(1):29–51. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.95.1.29

Flynn, J.R. and M. Shayer. (2018). IQ decline and Piaget: Does the rot start at the top? Intelligence 66: 112-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2017.11.010

Frost, P. (2019). Demise of the West. Evo and Proud, January 7. https://evoandproud.blogspot.com/2019/01/demise-of-west.html

Frost, P. (2022). Europeans and recent cognitive evolution. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 12.

Gottfredson, L. S., and I.J. Deary. (2004). Intelligence Predicts Health and Longevity, but Why? Current Directions in Psychological Science 13(1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01301001.x

hbd*chick (2013). A response to a response to two critical commentaries on woodley, te nijenhuis and murphy. May 27. http://hbdchick.wordpress.com/2013/05/27/a-response-to-a-response-to-two-critical-commentaries-on-woodley-te-nijenhuis-murphy-2013/

Hõrak, P., and M. Valge. (2015). Why did children grow so well at hard times? The ultimate importance of pathogen control during puberty. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health 1: 167–178, https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eov017

Howard, R. W. (1999). Preliminary real-world evidence that average human intelligence really is rising. Intelligence 27: 235-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00018-5

Howard, R. W. (2001). Searching the real world for signs of rising population intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences 30: 1039-1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00095-7

Howard, R. W. (2005). Objective evidence of rising population ability: A detailed examination of longitudinal chess data. Personality and Individual Differences 38(2): 347-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.04.013

Hugh-Jones, D., and A. Abdellaoui. (2022). Human Capital Mediates Natural Selection in Contemporary Humans. Behavior Genetics 52: 205-234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-022-10107-w

Kong, A., M.L. Frigge, G. Thorleifsson, H. Stefansson, A.I. Young, F. Zink, G.A. Jonsdottir, A. Okbay, P. Sulem, G. Masson, D.F. Gudbjartsson, A. Helgason, G. Bjornsdottir, U. Thorsteinsdottir, and K. Stefansson. (2017). Selection against variants in the genome associated with educational attainment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(5): E727-E732. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1612113114

Lappegård, T., Rønsen, M., and Skrede, K. (2011). Fatherhood and fertility. Fathering 9(1): 103-120. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0901.103

Madison, G. (2014). Increasing simple reaction times demonstrate decreasing genetic intelligence in Scotland and Sweden. London Conference on Intelligence. Psychological comments, April 25, #LCI14 Conference proceedings. http://www.unz.com/jthompson/lci14-questions-on-intelligence/

Madison, G., M.A. Woodley of Menie, and J. Sänger. (2016). Secular Slowing of Auditory Simple Reaction Time in Sweden (1959-1985). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, August 18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00407

Pietschnig, J., and M. Voracek. (2015). One Century of Global IQ Gains: A Formal Meta-Analysis of the Flynn Effect (1909-2013). Perspectives on Psychological Science 10(3): 282-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615577701

Piffer, D. (2019). Evidence for Recent Polygenic Selection on Educational Attainment and Intelligence Inferred from Gwas Hits: A Replication of Previous Findings Using Recent Data. Psych 1(1): 55-75. https://www.mdpi.com/2624-8611/1/1/5

Sieczkowksi, C. (2013). 1912 Eighth-Grade Exam Stumps 21st-Century Test Takers. Could You Pass This Eighth-Grade Exam from 1912? Huffpost, August 12. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/1912-eighth-grade-exam_n_3744163

Silverman, I. W. (2010). Simple reaction time: It is not what it used to be. The American Journal of Psychology 123(1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.123.1.0039

Thomson, E., T. Lappegård, M. Carlson, A. Evans, and E. Gray (2014). Childbearing across partnerships in Australia, the United States, Norway, and Sweden. Demography 51(2): 485-508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0273-6

Valge, M., R. Meitern, and P. Hõrak. (2022). Sexually antagonistic selection on educational attainment and body size in Estonian children. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1516(1): 271-285. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14859

Wikipedia (2022). Abortion in Iceland. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abortion_in_Iceland

Woodley, M.A., J. Nijenhuis, and R. Murphy. (2013). Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a meta-analysis of the slowing of simple reaction time. Intelligence 41: 843-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2013.04.006

The opening scene of the movie Idiocracy sums this up in a funnier and more accessible way:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sP2tUW0HDHA

Elon Musk knows about this. In Ashlee Vance's biography of Musk, there is a passage about Elon saying that smart people should have more kids. That's why he keeps having kids with a lot of different women.

Because it is so central to your argument, I think that you need a very specific and measurable definition of “middle class.”