How real was the Flynn effect?

Or did we just get more accustomed to standardized written tests?

New McGuffey Third Reader, 1901. It was used by children with a mean IQ 35 points lower than that of children today.

How real was the Flynn effect? Did we become more intelligent during the 20th century? Or just more accustomed to standardized written tests when they were introduced into schools after WWI and as education lengthened in the decades after WWII?

Did we become a lot more intelligent during the twentieth century? That seems to be what IQ scores tell us. Mean IQ rose by 35 points from 1920 to 2013, with almost a third of the increase being in the 1920s and early 1930s. Since the turn of the millennium, the trend has leveled off throughout the Western world and even reversed in Scandinavia.

The increase can be broken down into five periods (Pietschnig & Voracek, 2015):

A very slow rise between 1909 and 1919 (0.80 points/decade)

A surge during the 1920s and early 1930s (7.2 points/decade)

A slower rise between 1935 and 1947 (2.1 points/decade)

A faster one between 1948 and 1976 (3.0 points/decade)

A slower one thereafter (2.3 points/decade).

Named the Flynn effect, after intelligence researcher James Flynn, this secular increase in mean IQ has been much debated. How real was it? Did people become smarter on average or just more accustomed to standardized written tests?

Let me review the evidence. In addition to IQ testing, I will discuss other ways of measuring the capacity for intelligence: brain size; alleles associated with educational attainment; reaction time; vocabulary size; Piagetian testing; and the challenges of contemporary culture.

Brain size

This measure is moderately correlated with IQ and is known from MRIs, autopsies, and anthropometric surveys (r = 0.2 to 0.4) (Lee et al., 2019).

Americans (Framingham Heart Study)

In Framingham, Massachusetts, three generations have been examined since 1948 to understand the causes of heart disease. In particular, yearly brain MRIs were done from 1999 to 2019 on participants born between 1902 and 1985 (4,506 individuals), as well as tests for logical memory, visual memory, abstract reasoning, similarities, visuospatial skill, language, and executive functioning.

For each successive decade of birth, brain volume increased by 1.7 cc for men and by 1.2 cc for women. The increase was significant, though small (by comparison, mean brain volume was 1,356 cc for men and 1,200 cc for women). Logical memory performance also improved. No information has been provided on the other measures of mental performance (DeCarli et al., 2023).

This finding seems to argue strongly for a real increase in the capacity for intelligence. On the other hand, the younger cohorts may have been bigger-brained because they came disproportionately from a different class of people. The older cohorts tended to be mill and factory workers, in contrast to the younger college-educated nurses and doctors:

Requirements for entry [into the Framingham Heart Study] were an age between 30 and 62 years at the time of first examination, with no history of heart attack or stroke. Due to lukewarm interest at first, doctors, nurses and healthcare workers volunteered for the study to set an example for patients. (Wikipedia, 2024b).

This influx of younger volunteers apparently explains the inverse correlation between participant age and educational level:

Logistic regression found a highly significant increase in likelihood of achieving a college education with each advancing decade of birth, reaching a peak probability of nearly 92% for women born in 1970 (p < 0.0001). (DeCarli et al., 2023)

College-educated nurses and doctors volunteered for the study to help publicize it to the community, and they tended to be younger than the other participants, hence the apparent increase in brain size over time. This explanation is further supported by a 2-way interaction between being a woman and having a college education (probably in nursing).

There also was a significant 2-way interaction between decade of birth and sex (p < 0.01) where women had more rapidly increasing likelihood of achieving a college education with advancing decade of birth, particularly between decades of birth spanning 1910–1950. (DeCarli et al., 2023)

British and Germans (autopsy studies)

Three autopsy datasets, one from the UK and two from Germany, show an increase in brain weight by year of birth from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth. In the British dataset, male brains increased by 52 grams and female brains by 23 grams. In the German dataset, male brains increased by 73 grams and female brains by 52 grams (Haug, 1984; Kretschmann et al., 1979; Miller & Corsellis, 1977; Woodley of Menie et al., 2016).

Again, we seem to have strong evidence for a real increase in the capacity for intelligence. Unfortunately, the datasets suffer from collection bias, particularly the earlier age cohorts. During the nineteenth century, autopsies were done disproportionately on charity cases and condemned criminals because of the stigma attached to cutting up a dead body:

Grounded in Christian attitudes regarding the connection between body and soul dissection was considered a “degrading and sacrilegious practice” and was something reserved as a form of extra punishment for executed criminals (Nystrom, 2011).

In addition to the religious belief that a corpse should remain intact, there were also social concerns over the postponement of the funeral service and the inability to display the body in an open casket. As autopsies became more acceptable during the twentieth century, they were increasingly performed on people who were neither criminal nor destitute. The increase in brain size may therefore reflect a more representative sampling of the population.

Americans (Forensic Anthropology Data Bank)

According to data from the Forensic Anthropology Data Bank, mean brain size increased among Americans between c. 1820 and c. 1920 with no further improvement during the time of the Flynn effect (Jantz & Jantz, 2016). The study’s authors are skeptical that this increase was due to better nutrition or less childhood disease. Infant mortality is a good proxy for both, and it did not begin to decline until c. 1900. Since we have no data from before 1820, the increase in brain size may be the tail-end of a longer-term increase that began in medieval times, and which was apparently driven by the sustained demographic expansion of middle-class lineages (Clark, 2007, 2009, 2023; Frost, 2022a; Frost, 2024; Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024).

This study also suffers from the collection bias described above, since it uses data primarily from autopsies.

Cranial size by decade of birth, American men and women (Jantz & Jantz, 2016)

Estonians (anthropometric survey)

In Soviet Estonia, cranial volume was measured for an anthropometric survey of students born between 1937 and 1962 (7,123 boys and 9,866 girls). Because the measurements were mandatory, there was no volunteer bias, and mortality bias was minimal because the participants were all younger than 20 (Hõrak & Valge, 2015; Valge et al., 2021; Valge et al., 2022).

Girls with larger crania were more likely to pursue higher education. They thus married later and had fewer children. Throughout the twentieth century, Estonian women with only primary education bore 0.5 to 0.75 more children on average than women with tertiary education. In contrast, higher education had no effect on male fertility. The most fertile men had average-sized crania.

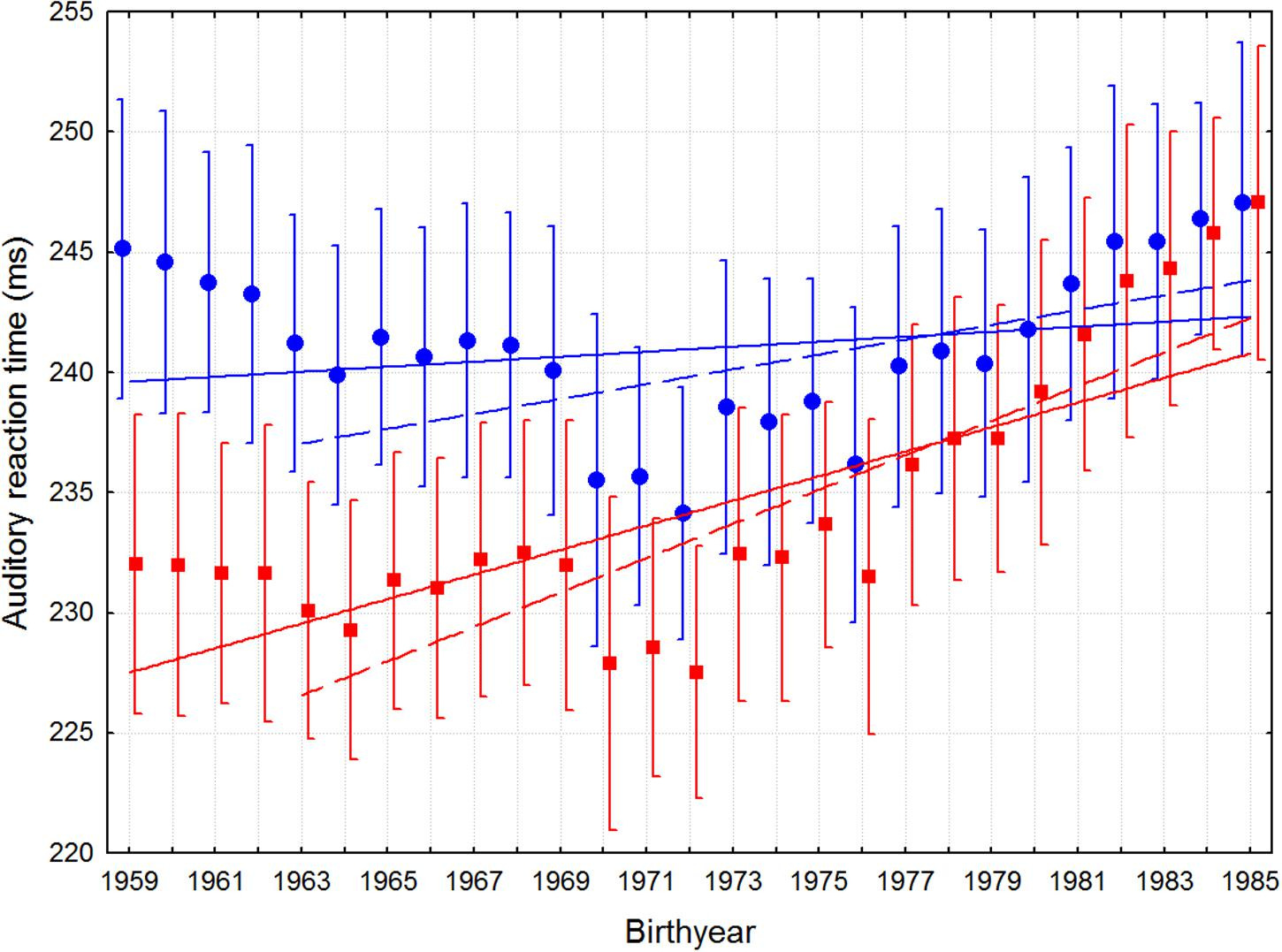

Alleles associated with educational attainment

This measure is the most promising one for assessing the capacity for intelligence. We construct it by first looking at the human genome, specifically at alleles associated with differences in educational attainment (EA), which is a good proxy for IQ. Such alleles have been identified at 1,271 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the genomes of over one million people of European ancestry. Using them, we can calculate a "polygenic score" (PGS) that explains 11-13% of the differences in EA among individuals (Lee et al., 2018). This score is a better measure of the mean IQ of a population than the IQ of any one individual. Intelligence researcher Davide Piffer has estimated a 90% correlation between the mean IQ of a population and its mean EA polygenic score (Piffer, 2019).

Although the EA polygenic score has been used to compare human populations, such use has been criticized on two grounds:

Rare alleles, which are more difficult to identify, contribute more to the intelligence of larger populations. We may thus underestimate the capacity for intelligence of larger populations in relation to smaller ones (Freese et al., 2019).

Different populations may not share the same alleles that contribute to intelligence. In this respect, the largest difference seems to exist between Eurasians and Sub-Saharan Africans. The EA polygenic score may thus underestimate the latter’s capacity for intelligence, since it is based on alleles identified from Europeans. In particular, it seems to underpredict African reading ability, perhaps because too many of the relevant alleles are exclusive to that gene pool and remain to be identified (Guo et al., 2022; Lasker et al., 2019; Rabinowitz et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2024).

Neither criticism applies to the polygenic studies I will discuss, which involve comparisons between successive age cohorts of a single population, i.e., European Americans, British people, or Icelanders. In all three populations, the mean polygenic score fell during the twentieth century from one cohort to the next.

European Americans

In this study, the genomic data came from Americans shortly before and during their retirement, specifically 11,822 Americans of European ancestry born between 1931 and 1953 (Beauchamp, 2016).

From 1931 to 1953, each successive age cohort had, on average, fewer alleles associated with high educational attainment. The decline seemed to be due to lower fertility among those participants who had pursued higher education. The mean EA polygenic score was thus significantly higher among the childless than among individuals with one or more children.

This study, like the next two, may suffer from survivorship bias — if you manage to live to an old age, you are probably smarter than average (Gottfredson & Deary, 2004). The bias must be small, however, since 85% of the original participants were still alive in 2008, the last year of genotyping.

Mean EA polygenic score as a function of lifetime reproductive success (LRS) (Beauchamp, 2016, Fig. 2)

British

In this study, the genomic data came from the UK Biobank, specifically 409,629 British individuals of European origin from two successive generations. The median birth year was 1950 for the second generation and unknown for the first (Hugh-Jones & Abdellaoui, 2022).

The mean EA polygenic score fell from the first generation to the second, particularly among lower-income people. Other alleles likewise changed in frequency between the two generations. In particular, the population became more prone to obesity, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depressive disorder, schizophrenia, neuroticism and — especially in men — extraversion.

This generational comparison may suffer from ascertainment bias because it necessarily excluded the childless individuals of the first generation. Another potential source of bias is the voluntary nature of contributions to the UK Biobank.

Icelanders

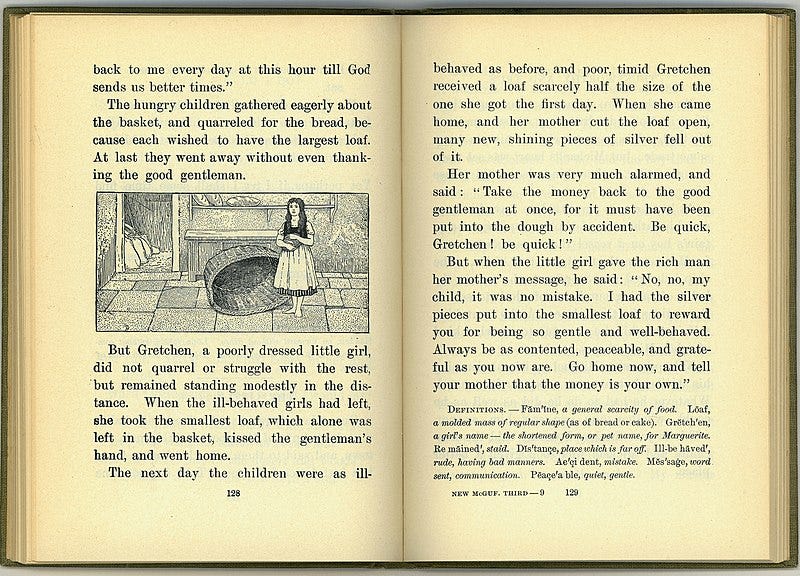

In this study, the genomic data came from a genealogical database (deCODE genetics), specifically 129,808 Icelanders born between 1910 and 1990 (Kong et al., 2017).

The mean EA polygenic score fell at a rate of about 0.010 standard deviation per decade. The decline was interrupted by two pauses: once in the 1950s and again in the 1970s. The first pause coincided with the postwar boom and a corresponding improvement in the ability of middle-class couples to start their families early in life. The second pause might reflect a law passed in 1975 to liberalize access to abortion in cases of rape, mental disability of the mother, and “difficult family situation” (Wikipedia, 2024a)

This genetic decline was due only in part to the more intelligent staying in school longer and postponing marriage. Some of it was independent of higher education, perhaps because smarter people tend to plan ahead and postpone family formation until they are financially ready.

Survivorship bias was low for the last five cohorts born since 1940, and especially low for those born in the 1970s and the 1980s.

Mean polygenic score of Icelanders by year of birth for alleles associated with educational attainment (Kong et al., 2017, Fig. 2)

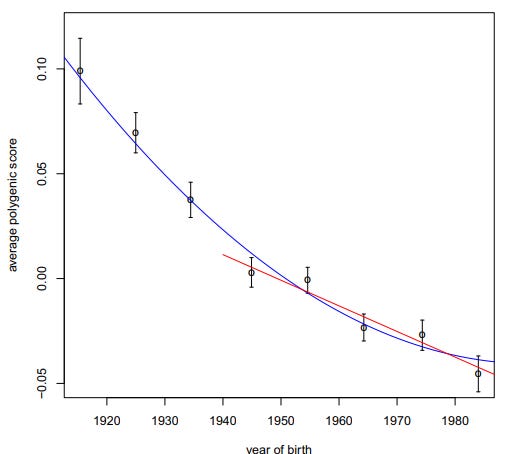

Reaction time

This measure is the speed at which the brain processes information. It has a moderate to high correlation with IQ (Der & Deary, 2017).

We seem to be taking longer to process the same amount of information. This is the conclusion that emerged when 14 studies, published since 1941, were compared with a study by Francis Galton from the late nineteenth century. With one exception, the post-1941 studies showed a lengthening of reaction time since the era of Galton’s study (Silverman, 2010). The corresponding decline in IQ is estimated at 1.23 points per decade, for a total loss of 14 points since the Victorian era (Woodley et al., 2013). Admittedly, the decline may be due to a more representative sampling of the population by later studies (hbd*chick, 2013).

On the other hand, a similar lengthening of reaction time has been shown by controlled studies with Swedish, Scottish, and American participants — particularly for cohorts born since 1980. The corresponding decline in IQ is likewise estimated at 1.3 to 1.7 points per decade (Madison, 2014; Madison et al., 2016).

Lengthening of reaction time of Swedish participants. The red squares are age-adjusted (Madison et al., 2016)

Vocabulary size

This measure is a key component of verbal intelligence tests, which are one of the highest-loading tests of general intelligence. To chart the changes over time in the number of words known and used by the average adult American, a research team examined data from the General Social Survey of U.S. adults (GSS) for the period from 1974 to 2016. The data came specifically from responses to 10 multiple-choice questions that required the respondent to define a word (Wordsum).

The researchers found that vocabulary size fell from the mid-1970s to the 2010s for all levels of educational attainment, especially the highest level. The decline was 8.5% overall. The cause cannot be ethnic change, since the decline was only a bit smaller among non-Hispanic European Americans. There was also a narrowing of the gap between Americans with no high school education and those with college education (Twenge et al., 2019).

This decline, however, can be explained by the lengthening of education, which has moved more and more medium-IQ Americans into the “college-educated” category and thereby reduced mean IQ at all levels of educational attainment. Thus, for the entire population, there was neither a Flynn effect nor a reversal of the Flynn effect during the 1974-2016 period (Kirkegaard, 2023).

Piagetian testing

This measure is highly correlated with IQ (r=0.51). Both are measures of speed, working memory, and complex reasoning (Rindermann & Ackermann, 2020).

When a research team examined the results of Piagetian tests in England and Wales from 1975-1976 to 2006-2007, they found that test scores began to fall after 1993, at a time when conventional IQ test scores were still rising. Moreover, the “smart fraction” was shrinking faster than the proportion of students who were simply above average:

The Piagetian results are particularly ominous … the pool of those who reach the top level of cognitive performance is being decimated: fewer and fewer people attain the formal level at which they can think in terms of abstractions and develop their capacity for deductive logic and systematic planning. (Flynn & Shayer, 2018)

Challenges of contemporary culture

This is a “soft” measure of the capacity for intelligence. It is less exact than the other measures, though less prone to the methodological issues that plague them.

Culture is a product of intelligence. It is the portion of our environment that we design and create through mental effort. Changes in mean IQ should thus be mirrored in contemporary culture, notably in entertainment, books and magazines, social activities, everyday tasks, and so on. In sum, culture reflects the sort of cognitive challenges we enjoy and feel comfortable with.

Intelligence researcher Robert Howard (1999, 2001, 2005) cites four pieces of evidence for a real increase in intelligence:

A decrease in the prevalence of mild mental retardation

An increase in the number of chess players reaching top performance at earlier ages

An increase in the number of journal articles and patents each year

An increase in the practical ability of schoolchildren, albeit without a corresponding increase in average general intelligence, in the ability to do school work, and in literacy skills (according to a survey of high school teachers who have taught for over 20 years).

The above evidence is debatable. Fewer children are diagnosed as mentally retarded because the term has become stigmatized. Prenatal screening has also had an impact. As for chess, it’s a niche activity that tells us little about the general population. More journal articles are indeed being published each year, but the reason has more to do with pressure to “publish or perish.”

Let me offer another piece of evidence: my personal experience with the different generations of the twentieth century. As a child, I knew adults whose mean IQ was supposedly a standard deviation below the mean IQ of Millennials. One of them was my mother. She never went further than Grade 10, yet she had a small library of books that she read and reread: half were on religious themes, often verse-by-verse commentaries on the Bible, and the others were popular fare like the Wizard of Oz. When I look through her books, I’m struck by the differences between them and the ones published today, not only in font size but also in vocabulary, sentence length, and sentence complexity. Again, this is circumstantial evidence, but I have trouble believing that the generations of the early twentieth century were substantially less intelligent than those of the late twentieth.

You might want to check out this exam. It was given in 1912 to Grade 8 pupils in Bullitt County, Kentucky.

Discussion

The Flynn effect does not look like a real increase in intelligence. It seems to be an increase in familiarity with standardized written tests, due to students staying in school longer and teachers abandoning other methods of evaluation, like essays and orally administered tests. On this last point, it is perhaps significant that the Flynn effect is absent from the Wordsum vocabulary test, which is shorter and simpler than a standard IQ test.

It is certainly significant that almost a third of the total Flynn effect occurred during the 1920s and early 1930s. This was when IQ testing, and standardized written evaluation in general, became much more widespread in American schools:

World War I, in effect, set in motion the process that would result – in an incredibly short time – in national intelligence testing for American school children. By the end of the first decade after the war, standardized educational testing was becoming a fixture in the schools. … The proponents of testing were extraordinarily successful: “... one of the truly remarkable aspects of the early history of IQ testing was the rapidity of its adoption in American schools nationwide.” (U.S. Congress, 1992, pp. 121-122)

After World War II, people became even more familiar with standardized written tests as more students went to college and university. The rise in postsecondary enrolment levelled off at about the same time as the Flynn effect, that is, shortly after the turn of the millennium.

Meanwhile, the capacity for intelligence had actually been falling from one generation to the next. The decline is shown by genome studies from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Iceland, all of which show a sustained decrease in alleles associated with high educational attainment during the twentieth century.

The main cause seems to be the tendency of the more intelligent to pursue higher education and thus postpone marriage and childbearing: “In all countries [Australia, United States, Norway, Sweden], however, education is negatively associated with childbearing across partnerships, and the differentials increased from the 1970s to the 2000s” (Thomson et al., 2014). Yet that isn’t the whole story. The above-mentioned Icelandic study found lower fertility among the more intelligent even after controlling for higher education (Kong et al., 2017).

It seems, then, that the capacity for intelligence fell throughout the twentieth century, even though the Flynn effect suggests the opposite. The decline became apparent only when the general population had become fully familiar with standardized written tests. But it had been happening all along.

That is my view, though others disagree. Two Norwegian researchers, Bratsberg and Rogeberg (2018), argue that the recent reversal of the Flynn effect in Norway can be explained by “within-family variation.” In other words, the IQ decline is driven by something that is affecting younger siblings much more than older siblings. Since siblings share the same genetic background, the cause must therefore be environmental.

Keep in mind, however, that siblings in Norway are increasingly half-siblings. Among Norwegian women with only two children, 13.4% have had them by more than one man. The figure rises to 24.9% among those with three children, 36.2% among those with four children, and 41.2% among those with five children (Thomson et al., 2014). If siblings have different fathers, they cannot share the same genetic background.

Who are the fathers of the younger siblings? The sort of men that single mothers often end up with, men of the lowest educational level:

At age 45, about 15 percent of all men in the 1960-62 cohort with a compulsory education had had children with more than one woman, compared to about 5 percent among men with a tertiary degree. If looking at fathers only (Figure 6), the pattern becomes even more pronounced. At the lowest educational level, 19.3 percent of those who had become fathers had children with more than one woman, compared to 6.1 percent of those at the highest educational level. (Lappegård et al., 2011)

The above paper goes on to note that "some of these men have never been in a stable relationship with the mother." One of them was Anders Breivik's stepfather:

My mother was infected by genital herpes by her boyfriend (my stepfather), Tore, when she was 48. Tore, who was a captain in the Norwegian Army, had more than 500 sexual partners and my mother knew this but suffered from lack of good judgement and moral due to several factors. (Breivik, 2011, p. 1171)

I still have contact with him although now he spends most his time (retirement) with prostitutes in Thailand. He is a very primitive sexual beast, but at the same time a very likable and good guy. (Breivik, 2011, p. 1387)

Thus ends a trajectory that took Western Europeans from relative unimportance to global dominance. It began in the late medieval period with the emergence of a middle class that specialized in trade or manufacture for trade. For these businesses, the workforce was the family. Successful individuals would expand their supply of workers by marrying young, by having many children and, later, by helping the latter do likewise. Hence the customary storefront sign: “So-and-so and Son.” With each generation, their lineages grew in number and shifted the gene pool further and further toward higher cognitive ability, lower time preference, stronger impulse control, and greater emphasis on foresight and planning. Their lineages came to dominate even the lower class through the downward mobility of “surplus” offspring. Culturally and genetically, the West was remade in the image of its growing middle class (Clark, 2007, 2009, 2023; Frost, 2022a; Frost, 2024; Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024).

In the late nineteenth century, this trajectory began to stall and go into reverse, as middle-class couples no longer translated their financial success into reproductive success. “Ma and pa” shops gave way to modern businesses, which could more readily expand or contract their supply of workers by simply hiring or firing them. So began a fertility decline that would briefly reverse during the postwar baby boom, when the fruits of economic growth were widely distributed and when cultural messaging was much more pro-family than it is today (Frost, 2019; Frost, 2022b).

The baby boom gave way to a baby bust and then a “family bust.” Today, the family unit is less concerned with perpetuating a lineage, and more with serving the interests of its current members.

References

Beauchamp, J.P. (2016). Genetic evidence for natural selection in humans in the contemporary United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(28), 7774-7779. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1600398113

Bratsberg, B., and Rogeberg, O. (2018). Flynn effect and its reversal are both environmentally caused. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(26), 6674-6678. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1718793115

Breivik, A. (2011). A European declaration of independence. https://archive.org/details/2083-a-european-declaration-of-independence

Clark, G. (2007). A Farewell to Alms. A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton University Press: Princeton. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691141282/a-farewell-to-alms

Clark, G. (2009). The domestication of man: the social implications of Darwin. ArtefaCToS 2: 64-80. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277275046_The_Domestication_of_Man_The_Social_Implications_of_Darwin

Clark, G. (2023). The inheritance of social status: England, 1600 to 2022. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120(27): e2300926120 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300926120

DeCarli, C., Pase, M., Beiser, A., Kojis, D., Satizabal, C., et al. (2023). Secular Trends in Head Size and Cerebral Volumes in the Framingham Heart Study for Birth Years 1902-1985. Research Square, January 30. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2524684/v1

Der, G., and Deary, I.J. (2017). The relationship between intelligence and reaction time varies with age: Results from three representative narrow-age age cohorts at 30, 50 and 69 years. Intelligence, 64, 89-97. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.intell.2017.08.001

Flynn, J.R. (1984). The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932–1978. Psychological Bulletin, 95(1), 29-51. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.95.1.29

Flynn, J.R. and Shayer, M. (2018). IQ decline and Piaget: Does the rot start at the top? Intelligence, 66, 112-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2017.11.010

Freese, J., Domingue, B., Trejo, S., Sicinski, K., & Herd, P. (2019). Problems with a Causal Interpretation of Polygenic Score Differences between Jewish and non-Jewish Respondents in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. SocArXiv, 10 July https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/eh9tq

Frost, P. (2019). Demise of the West. Evo and Proud, January 7. https://evoandproud.blogspot.com/2019/01/demise-of-west.html

Frost, P. (2022a). Europeans and recent cognitive evolution. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 12.

Frost, P. (2022b). The Great Decline. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, December 20.

Frost, P. (2024). Cognitive evolution in Europe: Two new studies. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, March 14.

Gottfredson, L. S., and Deary, I.J. (2004). Intelligence Predicts Health and Longevity, but Why? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01301001.x

Guo, G., Lin, MJ. & Harris, K.M. (2022). Socioeconomic and genomic roots of verbal ability from current evidence. npj Science of Learning, 7(1), 22 (2022). ttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-022-00137-8

Haug, H. (1984). Der Einfluß der säkularen Acceleration auf das Hirngewicht des Menschen und dessen Änderung während der Alterung. Gegenbaurs Morphologisches Jahrbuch, 130, 481–500

hbd*chick (2013). A response to a response to two critical commentaries on woodley, te nijenhuis and murphy. May 27. http://hbdchick.wordpress.com/2013/05/27/a-response-to-a-response-to-two-critical-commentaries-on-woodley-te-nijenhuis-murphy-2013/

Hõrak, P., and Valge, M. (2015). Why did children grow so well at hard times? The ultimate importance of pathogen control during puberty. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, 1, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eov017

Howard, R. W. (1999). Preliminary real-world evidence that average human intelligence really is rising. Intelligence, 27, 235-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00018-5

Howard, R. W. (2001). Searching the real world for signs of rising population intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 1039-1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00095-7

Howard, R. W. (2005). Objective evidence of rising population ability: A detailed examination of longitudinal chess data. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(2), 347-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.04.013

Hugh-Jones, D., and Abdellaoui, A. (2022). Human Capital Mediates Natural Selection in Contemporary Humans. Behavior Genetics, 52, 205-234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-022-10107-w

Jantz, R. L., & Jantz, L. M. (2016). The remarkable change in Euro-American cranial shape and size. Human biology, 88(1), 56-64. https://doi.org/10.13110/humanbiology.88.1.0056

Jellinghaus, K., Katharina, H., Hachmann, C., Prescher, A., Bohnert, M., & Jantz, R. (2018). Cranial secular change from the nineteenth to the twentieth century in modern German individuals compared to modern Euro-American individuals. International Journal of Legal Medicine, 132, 1477-1484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-018-1809-5

Kirkegaard, E. (2023). New study didn’t really show IQ declines. Just Emil Kirkegaard Things. March 12.

Kong, A., Frigge, M.L., Thorleifsson, G., Stefansson, H., Young, A.I., Zink, F., Jonsdottir, G.A., Okbay, A., Sulem, P., Masson, G., Gudbjartsson, D.F., Helgason, A., Bjornsdottir, G., Thorsteinsdottir, U., and Stefansson, K. (2017). Selection against variants in the genome associated with educational attainment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(5), E727-E732. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1612113114

Kretschmann, H. -J., Schleicher, A., Wingert, F., Zilles, K., & Löblich, K. -J. (1979). Human brain growth in the 19th and 20th century. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 40, 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-510X(79)90202-8

Lappegård, T., Rønsen, M., and Skrede, K. (2011). Fatherhood and fertility. Fathering, 9(1), 103-120. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0901.103

Lasker, J., Pesta, B.J., Fuerst, J.G.R., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2019). Global Ancestry and Cognitive Ability. Psych, 1, 431-459. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych1010034

Lee, J.J., McGue, M., Iacono, W.G., Michael, A.M., and Chabris, C.F. (2019). The causal influence of brain size on human intelligence: Evidence from within-family phenotypic associations and GWAS modeling. Intelligence, 75, 48-58. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.intell.2019.01.011

Lee, J. J., Wedow, R., Okbay, A., Kong, E., Maghzian, O., Zacher, et al. (2018). Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nature Genetics, 50(8), 1112-1121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3

Madison, G. (2014). Increasing simple reaction times demonstrate decreasing genetic intelligence in Scotland and Sweden. London Conference on Intelligence. Psychological comments, April 25, #LCI14 Conference proceedings. http://www.unz.com/jthompson/lci14-questions-on-intelligence/

Madison, G., Woodley of Menie, M.A., and Sänger, J. (2016). Secular Slowing of Auditory Simple Reaction Time in Sweden (1959-1985). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, August 18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00407

Miller, A.K.H., and Corsellis, J.A.N. (1977). Evidence for a secular increase in human brain weight during the past century. Annals of Human Biology, 4, 253–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014467700007142

Nystrom, K.C. (2011). Postmortem examinations and the embodiment of inequality in 19th century United States. International Journal of Paleopathology, 1(3-4), 164-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpp.2012.02.003

Pietschnig, J., and Voracek, M. (2015). One Century of Global IQ Gains: A Formal Meta-Analysis of the Flynn Effect (1909-2013). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(3), 282-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615577701

Piffer, D. (2019). Evidence for Recent Polygenic Selection on Educational Attainment and Intelligence Inferred from Gwas Hits: A Replication of Previous Findings Using Recent Data, Psych 1(1), 55-75. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych1010005

Piffer, D., and Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2024). Evolutionary Trends of Polygenic Scores in European Populations from the Paleolithic to Modern Times. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 27(1), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2024.8

Rabinowitz, J.A., Kuo, S.I.C., Felder, W., Musci, R.J., Bettencourt, A., Benke, K., ... & Kouzis, A. (2019). Associations between an educational attainment polygenic score with educational attainment in an African American sample. Genes, Brain and Behavior, e12558. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12558

Rindermann, H., and Laura Ackermann, A. (2021). Piagetian Tasks and Psychometric Intelligence: Different or Similar Constructs? Psychological Reports, 124(6), 2795-2821. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294120965876

Sieczkowksi, C. (2013). 1912 Eighth-Grade Exam Stumps 21st-Century Test Takers. Could You Pass This Eighth-Grade Exam from 1912? Huffpost, August 12. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/1912-eighth-grade-exam_n_3744163

Silverman, I. W. (2010). Simple reaction time: It is not what it used to be. The American Journal of Psychology, 123(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.123.1.0039

Thomson, E., Lappegård, T., Carlson, M., Evans, A., and Gray, E. (2014). Childbearing across partnerships in Australia, the United States, Norway, and Sweden, Demography 51(2), 485-508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0273-6

Twenge, J.M., Campbell, W.K., and Sherman, R.A. (2019). Declines in vocabulary among American adults within levels of educational attainment, 1974-2016. Intelligence, 76, 101377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2019.101377

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. (1992). Testing in American Schools: Asking the Right Questions, OTA-SET-519, Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Valge, M., Horak, P., and Henshaw, J.M. (2021). Natural selection on anthropometric traits of Estonian girls. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42(2), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.07.013

Valge, M., Meitern, R., and Hõrak, P. (2022). Sexually antagonistic selection on educational attainment and body size in Estonian children. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences,1516(1), 271-285. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14859

Wikipedia (2024a). Abortion in Iceland. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abortion_in_Iceland

Wikipedia. (2024b). Framingham Heart Study. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Framingham_Heart_Study

Woodley, M.A., Nijenhuis, J., and Murphy, R. (2013). Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a meta-analysis of the slowing of simple reaction time. Intelligence, 41, 843-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2013.04.006

Woodley of Menie, M.A., Peñaherrera, M.A., Fernandes, H.B.F., Becker, D., and Flynn, J.R. (2016). It's getting bigger all the time: Estimating the Flynn effect from secular brain mass increases in Britain and Germany. Learning and Individual Differences, 45, 95-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.11.004

Xia, R., Jian, X., Rodrigue, A. L., Bressler, J., Boerwinkle, E., Cui, B., ... & Fornage, M. (2024). Admixture mapping of cognitive function in diverse Hispanic and Latino adults: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Alzheimer's & Dementia, July 1, early view. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14082

Is the 8th grade exam supposed to be impressive? It looks quite easy, and at least the math (arithmetic) sections looks to be at a lower level than what current 8th graders are taught in most Western countries.

Thanks for the interesting article Peter.

I'm curious, your conclusion appears to be that the Flynn effect is in essence not "real" (i.e., not measuring what we really care about w.r.t increasing IQ) at a population level.

Then does that suggest that at the individual level one could improve their IQ? If so, isn't this a highly controversial claim in your field?

Further, wouldn't it suggest that IQ is becoming a worse rather than better at approximating somebody's level of intelligence?

Thanks again for the interesting piece.