Emotional responses to the differing skin tones of men and women

Skin color was gendered before it was racialized

Centaur figure in a mosaic at Hadrian’s villa (Wikicommons)

The hue and brightness of skin affects how we perceive each other. A lighter color makes the observer more empathic and less aggressive, while a darker, ruddier one has the reverse effect. These seem to be evolved responses to the differing skin tones of women and men.

Women are the “fair sex” because their skin has less melanin and less hemoglobin. They thus look pale in comparison to men, who are darker and ruddier. The cause is hormonal, as shown by studies of normal, castrated, and ovariectomized individuals, as well as by a digit ratio study (Edwards & Duntley, 1939; Edwards & Duntley, 1949; Edwards et al., 1941; Manning et al., 2004).

This sex difference once accounted for most of the variation in skin color within any human group. There is thus a strong cross-cultural tendency to associate darker skin with men and lighter skin with women (Frost, 2010; Frost, 2011; Frost, 2023; van den Berghe & Frost, 1986). This is also why many cultures have independently developed the artistic convention of using a lighter shade for women and a darker one for men (Capart 1905, pp. 26-27; Eaverly 2013; Pallottino 1952, pp. 34, 45, 73, 76-77, 87, 93, 95, 105, 107, 115; Soustelle 1970, p. 130; Tegner 1992; Wagatsuma 1967).

Even AI picks up on this sex difference (Cutler, 2025).

We still associate darker skin with men and lighter skin with women, if only subconsciously. Moreover, as shown by several controlled studies, we use this sex difference to tell male and female faces apart, especially if face shape is poorly visible. The main visual cue is the skin’s brownness and ruddiness. If the face is too far away or the lighting too dim, our mind switches to the more time-consuming but accurate cue of brightness. Facial color is thus perceived through a mechanism that served originally to tell men and women apart, even though ethnicity increasingly explains the differences we see among people we regularly meet (Dupuis-Roy et al. 2009; Dupuis-Roy et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2015; Nestor & Tarr, 2008a; Nestor & Tarr, 2008b; Tarr et al., 2001; Tarr et al., 2002; Yip & Sinha, 2002).

In sum, we are hardwired to see darker faces as male and lighter faces as female. This is seen in studies of people who are shown faces and asked to perform certain tasks:

Make pictures of faces more attractive by varying their skin color. Male faces are made darker and ruddier than female ones (Carrito et al., 2016).

Assess the skin color of faces. Female faces are judged to be lighter-skinned than male ones, even though most of the participants deny that skin color differs between men and women (Carrito & Semin, 2019).

View several faces (of identical skin color). Then use your memory to identify each of them from a row of faces (which vary only in skin color). People respond by choosing lighter versions of the original female faces and darker versions of the original male faces, even though the original faces were all the same color (Carrito & Semin, 2019).

Even inanimate objects are unthinkingly gendered in the same way:

Identify personal names by gender. Names are identified faster by gender when male names are presented in black and female names in white (Semin et al., 2018).

Classify briefly appearing blobs by gender. Black blobs are classified predominantly as male and white blobs as female (Semin et al., 2018).

Observe light and dark objects, while having your eye movements tracked. Observation is longer and fixation more frequent when a dark object is associated with a male character and a light object with a female character (Semin et al., 2018).

This hardwired mechanism has two complementary functions: evaluate the person you observe and modify your emotional state accordingly. The second function is best understood by understanding how women came to be lighter-skinned than men.

A lighter skin color is one of several infant traits that the adult female body seems to mimic, the others being a smaller nose and chin, a smoother and more pliable skin texture, and a higher pitch of voice. This is what ethologist Konrad Lorenz called the Kindchenschema — a set of visual, tactile, and auditory cues that identify an infant to an adult, who responds by feeling less aggressive and more willing to defend and nurture. In a word, the infant seems “cute” (Frost, 2010, pp. 134-135; Lorenz, 1971, pp. 154-164).

An infant’s pale skin is especially apparent in societies where adults are dark-skinned. A new Kenyan mother may tell her neighbors to come and see her mzungu, i.e., “European” (Walentowitz, 2008). When an anthropologist asked Zambian girls to describe how Africans look, some wrote: “At birth African children are born like Europeans, but after a few months the color changes to the color of an African” (Powdermaker, 1956).

The newborn’s light color is often attributed to a previous spirit life:

There is a rather widespread concept in Black Africa, according to which human beings, before “coming” into this world, dwell in heaven, where they are white. For, heaven itself is white and all the beings dwelling there are also white. Therefore the whiter a child is at birth, the more splendid it is. In other words, at that particular moment in a person's life, special importance is attached to the whiteness of his colour, which is endowed with exceptional qualities. (Zahan, 1974, p. 385)

As long as this light coloration persists, a newborn African is considered soft and vulnerable, and hence at risk of returning to heaven.

… it is also claimed that a newborn baby is not only white but also a soft being during the time between his birth and his acceptance into the society. (Zahan, 1974, p. 386-387)

This infant coloration is also apparent in many nonhuman primates. Langurs, baboons, and macaques are born pink and later darken, becoming almost black in adulthood. Their fur, too, is lighter at birth and darkens with age. The light coloration seems to make nearby adults more caring and protective. As the infant darkens with age, its mother no longer seeks it out to hold and fondle (Alley, 1980; Alley, 2014; Booth, 1962; Guthrie, 1970; Jay, 1962).

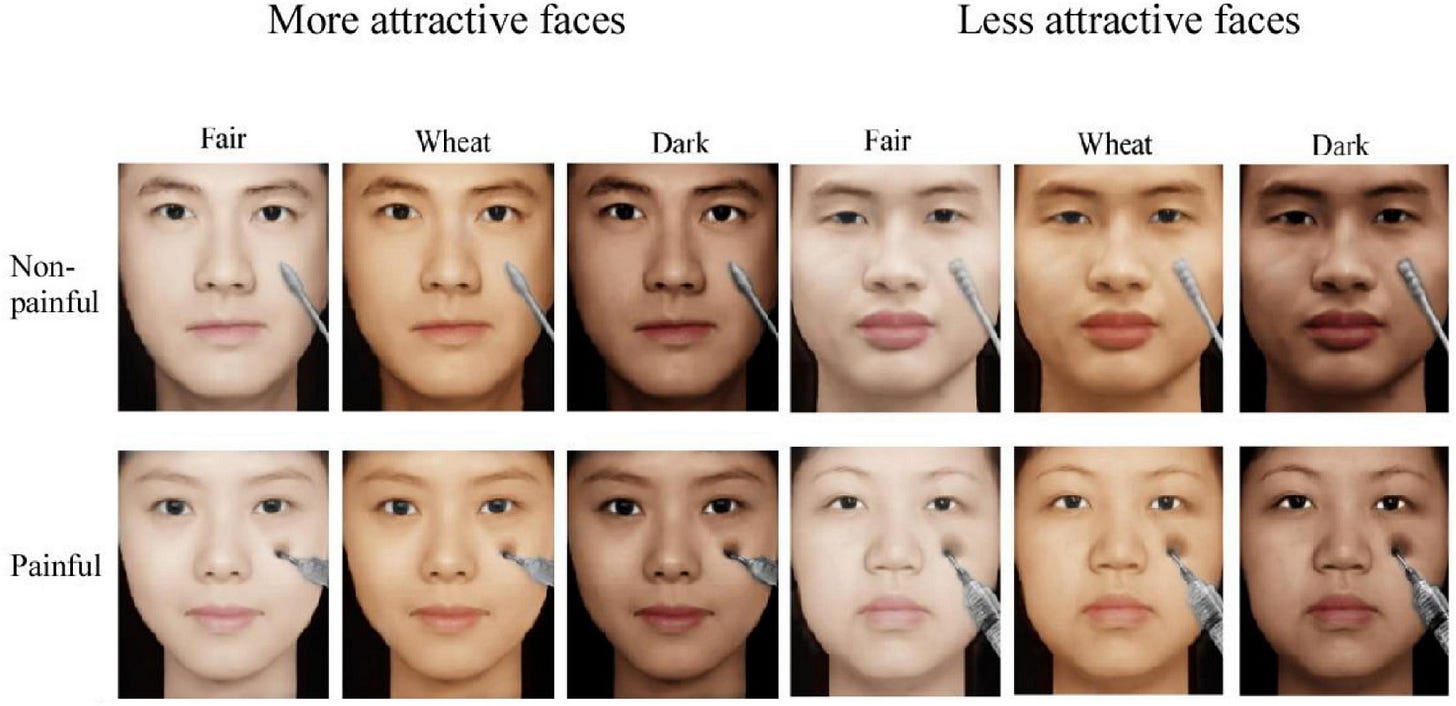

This change in emotional state has been studied in humans by a Chinese research team. The participants were shown a series of attractive or unattractive Chinese faces that varied in skin color and seemed to be either in pain (with a syringe needle sticking into a cheek) or not in pain (with a Q-tip touching a cheek). For each face, the participant had to judge whether it was experiencing pain. Reaction time was measured, as was brain activity on an electroencephalogram (EEG).

When the faces were attractive and seemingly in pain, the lighter ones were judged to be suffering more than the darker ones. Also, reaction time was shorter, and the EEGs showed a higher level of empathy. But this difference was absent for unattractive faces. Only when the face was both light-skinned and attractive did the observer feel more empathy if the face seemed to be in pain (Yang et al., 2022).

Why would an observer feel more empathy for a light-skinned person in pain? This may have originated as a response to seeing an infant or a woman in danger. In both cases, light skin is a visual cue for the Kindchenschema. Darker and ruddier skin would conversely evoke the image of an adult male, and make the observer less empathetic.

But why would light skin have this effect only if the face is attractive? The empathic response is probably stimulated by the entire Kindchenschema — not only lighter skin, but also bigger eyes and a less protruding chin and jaw. These visual cues probably interact with each other: a “cute” facial feature would increase the empathic effect of other “cute” features, whereas an “ugly” feature would have the reverse effect.

The lighter faces were judged to be in greater pain. Reaction time was also shorter, and the EEGs indicated more empathy (Yang et al., 2022)

This relationship between skin color and the observer’s emotional state is consistent with previous research findings. Let’s review the literature to understand how the different skin tones of men and women affect an observer’s emotional state.

General perceptions of male redness

We will first consider the redness of a male body. How does it affect the observer? This question has sparked much research since a high-profile finding two decades ago.

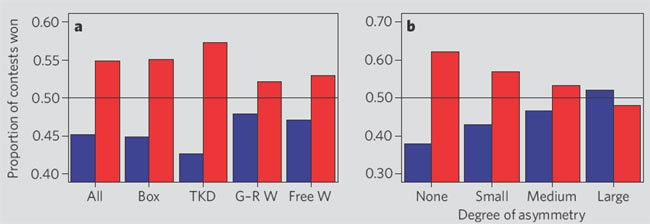

At the 2004 Olympic Games, athletes won more often with red uniforms than with blue ones. In man-to-man contests of boxing, taekwondo, Greco-Roman wrestling, and freestyle wrestling, contestants with red uniforms won 16 out of 21 rounds. Contestants with blue uniforms won only 4 rounds. The red uniforms seem to have been more intimidating, perhaps because dominant males have more testosterone and, hence, a ruddier color (Hill & Barton, 2005). This finding has been corroborated by two other studies, which likewise conclude that red clothing makes a man seem more dominant and threatening (Feltman & Elliot, 2011; Wiedemann et al., 2015).

Even redness by itself seems to make an observer more cautious, more compliant, more aggressive, or more submissive. This has been shown by studies of people who are asked to perform certain tasks with differently colored objects or surroundings:

Identify the color of words on a computer screen. Men take longer than women to answer when the words are in red (Ioan et al., 2007).

Identify the incorrect idiom from a list of idioms. The error rate is higher when the idioms are in red than when they are in blue (Shi et al., 2015).

Exercise on a stationary bicycle in a red environment. Covered distance and heart rate are lower in a red environment than in a green or gray one, while enjoyment is higher in a green environment than in a red one (Briki et al., 2015).

Make bids at an auction and make price offers during negotiations. A red background is associated with higher jumps in bids at an auction and lower offers during negotiations (Bagchi & Cheema, 2012).

Respond to the message in an advertisement. Compliance is higher when a message is shown against a red background (Kareklas et al., 2019).

The redness effect varies with context. It is least apparent when redness is presented alone or overwhelmed by a much stronger effect; for example, English soccer teams have the same home advantage with or without red shirts (Allen & Jones, 2014). It becomes more apparent when redness is associated with a facial photo, rather than a simplified drawing of a face, and even more apparent when the face is attractive (Buechner et al., 2014; Pazda et al., 2023; Schwarz & Singer, 2013; Wen et al., 2014; Young, 2015).

Redness also affects the perceived passage of time. When a red screen and a blue screen are seen for the same duration, the red screen is perceived as lasting longer. The overestimation is greater for men than for women. People also react faster to the red screen than to the blue screen, and the difference in reaction time correlates with the tendency to overestimate red-screen duration. It seems that “the arousal induced by red increases the speed of the internal clock” (Shibasaki & Masataka, 2014).

Finally, redness can help distinguish between facially similar emotions, such as anger versus disgust, surprise versus fear, and sadness versus happiness (Thorstenson et al., 2019a; Thorstenson et al., 2021). When faces are viewed against a red background, people take less time to identify a face as angry than they do to identify a face as happy or fearful (Young et al., 2013).

Lack of redness, as when a face turns pale with fright, has the reverse effect: it appeases the observer and de-escalates conflict. When people are asked to rate their propensity for turning pale, the highest scores come from those who fear blood and injury. Women score higher on average than men (Drummond, 1997).

What about a face turning red with embarrassment? Like anger, blushing serves to keep the observer at a distance, being a sort of controlled anger due to embarrassment (Drummond, 1997). If a person blushes while making an apology, the observer will more likely perceive it as sincere and be more forgiving (Thorstenson et al., 2019b). Blushing seems to be heritable. Darwin cited the case of a father, mother, and ten children, “all of whom, without exception, were prone to blush to a most painful degree” (Darwin, 1872, p. 312).

Left: Olympic contests won by color of uniform (red or blue) for all sports, for boxing, for taekwondo, for Greco-Roman wrestling, and for freestyle wrestling. Right: Proportion of contests won by color of uniform (red or blue) and by difference in skill and strength (degree of asymmetry). The color difference seems to matter most for contestants of equal skill and strength (Hill & Barton, 2005)

General perceptions of male darkness

We will now consider the darkness of a male body. The relevant literature is mostly about color symbolism in different cultures.

The ancient Greeks believed that a woman’s light color incarnated her “helplessness and need of protection” and a man’s dark color his “courage and the ability to fight well” (Irwin 1974, p. 121). A brave man had a “black rump”, and a coward a “white rump.” The same mental association was projected onto the internal organs and ultimately onto the soul. A “black heart” denoted strong emotions, and a “white heart” indifference or a refusal to act. A coward had a “white liver,” a metaphor that survives in the expression “lily-livered” (Irwin 1974, pp. 129-155).

Cross-culturally, whiteness evokes weakness and blackness strength (Gergen 1967, p. 397; Osgood 1960, p. 165). According to a Turkish study, blackness is associated with power, fear, courage, and eternity, and redness with courage, enthusiasm, fun, and anxiety. In contrast, whiteness is associated with cleanliness, honesty, peace, and hope (Demir, 2020). A study with participants from China, Germany, Greece, and the UK found that “BLACK and RED evoked more consistent colour–emotion association patterns than other colour terms. BLACK and RED colour terms were also more commonly associated with strong emotions, and evoked a larger number of associated emotions than many other colour terms” (Jonauskaite et al., 2019).

There is a similar pattern in a study of rural French Canadians. Darker men were perceived as being stronger and more virile in physique and character. If a man was too dark, he would be considered quick-tempered, arrogant, and malicious. Women were expected to be fairer-skinned, although their lighter color was likewise associated with weakness of physique and character (Frost, 2010, pp.149-152).

Female perceptions of male redness/darkness

We will now turn to gender-specific perceptions. How do women respond to the redness of a male body? How does it affect their emotional state?

According to one study, women associate high levels of male ruddiness with aggression, medium levels with dominance, and low levels with attractiveness (Stephen et al., 2012). According to another study, women judge men to be more attractive when viewed against a red background and in red clothing. This effect is confined to sexual attractiveness and does not change the man’s overall likability (Elliot et al., 2010). These findings seem contradictory: male attractiveness is associated with a low level of redness in one study and a high level in the other. Perhaps the word “attractiveness” was construed aesthetically by the women of the first study and erotically by those of the second.

How do women respond to the darkness of a male body? Their response seems to be hormonally influenced, as shown by two studies:

Choose between two male faces that differ slightly in color. The darker face is more often preferred during the first two-thirds of the menstrual cycle than during the last third, although the lighter face is always the majority preference. During the first two-thirds of the cycle, the level of estrogen is high in relation to the level of progesterone (which acts as an anti-estrogen). During the last third, the ratio is reversed, with estrogen being low relative to progesterone. There is no cyclical change in preference when participants view female faces or have taken oral contraceptives (Frost, 1994).

View male faces during a brain MRI. Women have a stronger neural response to masculinized male faces than to feminized ones. The intensity of the response correlates with the rise and fall of estrogen levels across the menstrual cycle. In a personal communication, the lead author stated that the faces were masculinized by making them darker and more robust in shape (Rupp et al., 2009).

An estrogenic effect is further suggested by a study of preschool children:

Choose between two dolls that differ slightly in skin color. Among boys and girls below three years of age, body fat is greater in those choosing the darker doll than in those choosing the lighter doll. In that age range, estrogen is produced mostly in fatty tissues (Frost, 1989).

To some extent, the above preferences can be triggered by red or dark clothing, as shown by a study of preferences for men or women dressed in blue, green, yellow, red, white, or black. Women prefer men dressed in red or black. The same colors are preferred when men are asked to judge women or men. But neither red nor black is preferred when women are asked to judge other women (Roberts et al., 2010).

Male perceptions of female redness/darkness

We will now look at things from a more paradoxical perspective — a woman’s body with male pigmentation. How do men respond to a reddened and darkened female body? How does it affect their emotional state?

Let’s first consider redness. Women with red clothes seem more attractive to men (Elliot & Niesta, 2008), but this effect is conditional. A woman with red clothes seems more attractive if she is already attractive, but not if she is masculine-looking, older, or unattractive (Pazda et al., 2023; Schwarz & Singer, 2013; Wen et al., 2014; Young, 2015). This effect is confined to sexual attractiveness and does not affect overall likability (Wen et al., 2014). Redness seems to intensify a man’s interest in a woman; if there is nothing of interest to begin with, there is nothing to intensify.

This finding is consistent with popular culture. The “lady in red” is a femme fatale:

In literature, red has repeatedly been associated with female sexuality, especially illicit sexuality, most famously in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic work The Scarlet Letter. Likewise, in popular stage and film, there are many instances in which red clothing, especially a red dress, has been used to represent passion or sexuality …

Red is paired with hearts on Valentine’s Day to symbolize romantic affection and is a highly popular color for women’s lingerie. Red has been used for centuries to signal sexual availability or “open for business” in red-light districts. Women commonly use red lipstick and rouge to heighten their attractiveness, a practice that has been in place at least since the time of the ancient Egyptians (Elliot & Niesta, 2008)

Let’s now consider how men respond to a darkened female body. When men are shown pictures of lighter-skinned and darker-skinned women, the two groups are judged to be equally attractive, but the men’s eye movements tell another story: the lighter-skinned women are viewed for a longer time than the darker-skinned ones (Garza et al., 2016). Given that the two groups of women arouse the same degree of sexual interest, the male response to darker women must be briefer and more intense. In other words, the same level of interest is concentrated within a shorter time.

This finding is consistent with popular culture. In English novels from the Victorian era, “the dark lady” is an “impetuous,” “ardent,” and “passionate” player in short-lived romances (Carpenter, 1936, p. 254). In French and German novels from that era, “the love incarnated by les brunes appears as the conceptual equivalent of a devouring femininity, thus making them similar to the mythical figure of Lilith.” (Atzenhoffer, 2011, p. 6). For one French writer, men who love les brunes “are generally taken by a passion that is more violent, more demonstrative, and more domineering, but also less profound, less tender, and less durable” (Briot, 2007).

But why, then, did women evolve lighter skin?

In sum, a dark, reddish color excites the observer much more than a lighter one. The effect is stronger if a dark or reddish color is associated with a human body and, even more so, with an attractive human face. Furthermore, it is as strong for a man observing a woman as it is for a woman observing a man. This excitation can increase sexual arousal, but at the cost of a steeper decline afterwards — perhaps because a higher level of arousal is exhausted more rapidly.

If a dark, reddish color increases sexual arousal not only when a woman is observing a man but also when a man is observing a woman, why, then, did women become less dark and less ruddy than men? Wouldn’t sexual selection have favored darker, ruddier women? For that matter, why is there any sex difference in skin color?

Perhaps the need to survive and procreate favored those women who could not only arouse sexual interest but also maintain it over the longer term. That goal would not be met if sexual interest were concentrated within a briefer but more intense interval. Thus, lighter female skin was favored not because it intensified male sexual interest but rather because it stabilized the pair bond through a decrease in male aggressiveness and an increase in male provisioning — by mimicking the Kindchenschema.

This is sexual selection in a broad sense: the pressure of selection extends beyond the moment of mate choice to the much longer period of cohabitation after mating.

References

Allen, M. S., & Jones, M. V. (2014). The home advantage over the first 20 seasons of the English Premier League: Effects of shirt colour, team ability and time trends. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(1), 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2012.756230

Alley, T. R. (1980). Infantile colouration as an elicitor of caretaking behaviour in Old World primates. Primates, 21(3), 416-429. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02390470

Alley, T.R. (2014[1986]). An ecological analysis of the protection of primate infants. In V. McCabe & G.J. Balzano (Eds.) Event Cognition: An Ecological Perspective. Routledge.

Atzenhoffer, R. (2011). Les hommes préfèrent les blondes. Les lectrices aussi. Effet de psychologie, horizons idéologiques et valeurs morales des héroïnes dans l'œuvre romanesque de H. Courths-Mahler. Colloque national (CNRIUT), Villeneuve d'Ascq, 8-10 juin 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20210921193948/http://cnriut09.univ-lille1.fr/articles/Articles/Fulltext/10a.pdf

Bagchi, R., & Cheema, A. (2013). The effect of red background color on willingness-to-pay: the moderating role of selling mechanism. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5), 947-960. https://doi.org/10.1086/666466

Booth, C. (1962). Some observations on behavior of Cercopithecus monkeys. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 102(2), 477-487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13654.x

Briki, W., Rinaldi, K., Riera, F., Trong, T. T., & Hue, O. (2015). Perceiving red decreases motor performance over time: A pilot study. European Review of Applied Psychology, 65(6), 301-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2015.09.001

Briot, E. (2007). Couleurs de peau, odeurs de peau : le parfum de la femme et ses typologies au xixe siècle. Corps, 2(3), 57-63. https://doi.org/10.3917/corp.003.0057

Buechner, V. L., Maier, M. A., Lichtenfeld, S., & Schwarz, S. (2014). Red-take a closer look. PloS one, 9(9), e108111. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108111

Capart, J. (1905). Primitive Art in Egypt. London: H. Grevel.

Carpenter, F. I. (1936). Puritans preferred blondes. The heroines of Melville and Hawthorne. New England Quarterly, 9(2), 253-272. https://doi.org/10.2307/360391

Carrito, M.L., dos Santos, I.M.B., Lefevre, C.E., Whitehead, R.D., da Silva, C.F., & Perrett, D.I. (2016). The role of sexually dimorphic skin colour and shape in attractiveness of male faces. Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(2), 125-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.09.006

Carrito, M. L., & Semin, G. R. (2019). When we don’t know what we know–Sex and skin color. Cognition, 191, 103972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.05.009

Cutler, A. (2025). Note.

Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: John Murray.

Demir, Ü. (2020). Investigation of color-emotion associations of the university students. Color Research & Application, 45(5), 871-884. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.22522

Drummond, P.D. (1997). Correlates of facial flushing and pallor in anger - provoking situations. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(4), 575-582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00077-9

Dupuis-Roy, N., Faghel-Soubeyrand, S., & Gosselin, F. (2019). Time course of the use of chromatic and achromatic facial information for sex categorization. Vision Research, 157, 36-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2018.08.004

Dupuis-Roy, N., Fortin, I., Fiset, D., & Gosselin, F. (2009). Uncovering gender discrimination cues in a realistic setting. Journal of Vision, 9(2), 10, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1167/9.2.10

Eaverly, M.A. (2013). Tan Men/Pale Women. Color and Gender in Archaic Greece and Egypt, a Comparative Approach. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.3080238

Edwards, E.A., & Duntley, S.Q. (1939). The pigments and color of living human skin. American Journal of Anatomy, 65(1), 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1002/aja.1000650102

Edwards, E.A., & Duntley, S.Q. (1949). Cutaneous vascular changes in women in reference to the menstrual cycle and ovariectomy. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 57(3), 501-509. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(49)90235-5

Edwards, E.A., Hamilton, J.B., Duntley, S.Q., & G. Hubert, G. (1941). Cutaneous vascular and pigmentary changes in castrate and eunuchoid men. Endocrinology, 28(1), 119-128. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-28-1-119

Elliot, A. J., & Niesta, D. (2008). Romantic red: red enhances men's attraction to women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1150. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1150

Elliot, A. J., Niesta Kayser, D., Greitemeyer, T., Lichtenfeld, S., Gramzow, R. H., Maier, M. A., & Liu, H. (2010). Red, rank, and romance in women viewing men. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139(3), 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019689

Feltman, R., & Elliot, A. J. (2011). The influence of red on perceptions of relative dominance and threat in a competitive context. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(2), 308-314. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.33.2.308

Frost, P. (1989). Human skin color: the sexual differentiation of its social perception. Mankind Quarterly, 30, 3-16. https://doi.org/10.46469/mq.1989.30.1.1

Frost, P. (1994). Preference for darker faces in photographs at different phases of the menstrual cycle: Preliminary assessment of evidence for a hormonal relationship. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 79(1), 507-14. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1994.79.1.507

Frost, P. (2010). Femmes claires, hommes foncés. Les racines oubliées du colorisme. Quebec City: Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 202 p. https://www.pulaval.com/livres/femmes-claires-hommes-fonces-les-racines-oubliees-du-colorisme

Frost, P. (2011). Hue and luminosity of human skin: a visual cue for gender recognition and other mental tasks. Human Ethology Bulletin, 26(2), 25-34. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256296588_Hue_and_luminosity_of_human_skin_a_visual_cue_for_gender_recognition_and_other_mental_tasks

Frost, P. (2023). The original meaning of skin color. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, March 20. https://www.anthro1.net/p/the-original-meaning-of-skin-color

Garza, R., Heredia, R.R., & Cieslicka, A.B. (2016). Male and female perception of physical attractiveness. An eye movement study. Evolutionary Psychology, 14(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1474704916631614

Gergen, K.J. (1967). The significance of skin color in human relations. Daedalus, 96, 390-406. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027044

Guthrie, R.D. (1970). Evolution of human threat display organs. In: Dobzhansky, T., Hecht, M.K., & Steere, W.C. (Eds.) Evolutionary Biology, 4, 257-302. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts.

Hill, R., & Barton, R. (2005). Red enhances human performance in contests. Nature, 435, 293. https://doi.org/10.1038/435293a

Ioan, S., Sandulache, M., Avramescu, S., Ilie, A., & Neacsu, A. (2007). Red is a distractor for men in competition. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 285-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.03.001

Irwin, E. (1974). Colour Terms in Greek Poetry. Toronto: Hakkert.

Jay, P.C. (1962). Aspects of maternal behavior among langurs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 102(2), 468-476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13653.x

Jonauskaite, D., Wicker, J., Mohr, C., Dael, N., Havelka, J., Papadatou-Pastou, M., ... & Oberfeld, D. (2019). A machine learning approach to quantify the specificity of colour–emotion associations and their cultural differences. Royal Society Open Science, 6(9), 190741. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190741

Jones, A.L., Russell, R., & Ward, R. (2015). Cosmetics alter biologically-based factors of beauty: evidence from facial contrast. Evolutionary Psychology, 13(1) https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491501300113

Kareklas, I., Muehling, D. D., & King, S. (2019). The effect of color and self-view priming in persuasive communications. Journal of Business Research, 98, 33-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.022

Lorenz, K. (1971). Studies in Animal and Human Behaviour, vol. 2. London: Methuen & Co.

Manning, J.T., Bundred, P.E., & Mather, F.M. (2004). Second to fourth digit ratio, sexual selection, and skin colour. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25(1), 38-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(03)00082-5

Nestor, A., & Tarr, M.J. (2008a). The segmental structure of faces and its use in gender recognition. Journal of Vision, 8(7), 7, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1167/8.7.7

Nestor, A., & Tarr, M.J. (2008b). Gender recognition of human faces using color. Psychological Science, 19(12), 1242-1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02232.x

Osgood, C.E. (1960). The cross-cultural generality of visual-verbal synesthetic tendencies. Behavioral Science, 5(2), 146-169. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830050204

Pallottino, M. (1952). Etruscan Painting. Lausanne: Skira.

Pazda, A. D., & Elliot, A. J. (2017). Processing the word red can enhance women’s perceptions of men’s attractiveness. Current Psychology, 36, 316-323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9420-8

Pazda, A. D., Thorstenson, C. A., & Elliot, A. J. (2023). The effect of red on attractiveness for highly attractive women. Current Psychology, 42(10), 8066-8073. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s12144-021-02045-3

Powdermaker, H. (1956). Social change through imagery and values of teen-age Africans in Northern Rhodesia. American Anthropologist, 58(5), 783-813 https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1956.58.5.02a00030

Roberts, S. C., Owen, R. C., & Havlicek, J. (2010). Distinguishing between perceiver and wearer effects in clothing color-associated attributions. Evolutionary Psychology, 8, 350–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491000800304

Rupp, H.A., James, T.W., Ketterson, E.D., Sengelaub, D.R., Janssen, E., & Heiman, J.R. (2009). Neural activation in women in response to masculinized male faces: mediation by hormones and psychosexual factors. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.08.006

Schwarz, S., & Singer, M. (2013). Romantic red revisited: Red enhances men’s attraction to young, but not menopausal women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.08.004

Semin, G.R., Palma, T., Acartürk, C., & Dziuba, A. (2018). Gender is not simply a matter of black and white, or is it? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 373(1752), 20170126. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0126

Shi, J., Zhang, C., & Jiang, F. (2015). Does red undermine individuals' intellectual performance? A test in China. International Journal of Psychology, 50(1), 81-84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12076

Shibasaki, M., & Masataka, N. (2014). The color red distorts time perception for men, but not for women. Scientific Reports, 4, 5899. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05899

Soustelle, J. (1970). The Daily Life of the Aztecs. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Stephen, I.D., Oldham, F.H., Perrett, D.I., & Barton, R.A. (2012). Redness enhances perceived aggression, dominance and attractiveness in men's faces. Evolutionary Psychology, 10(3) https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491201000312

Tarr, M.J., Kersten, D., Cheng, Y., & Rossion, B. (2001). It's Pat! Sexing faces using only red and green. Journal of Vision, 1(3), 337, 337a. https://doi.org/10.1167/1.3.337

Tarr, M. J., Rossion, B., & Doerschner, K. (2002). Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: Behavioral and neural correlates of face sexing using color. Journal of Vision, 2(7), 598, 598a. https://doi.org/10.1167/2.7.598

Tegner, E. (1992). Sex differences in skin pigmentation illustrated in art. The American Journal of Dermatopathology, 14(3), 283-287. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000372-199206000-00016

Thorstenson, C.A. (2018). The social psychophysics of human face color: Review and recommendations. Social Cognition, 36(2), 247-273. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2018.36.2.247

Thorstenson, C.A., Pazda, A.D., Young, S.G., & Elliot, A.J. (2019a). Face color facilitates the disambiguation of confusing emotion expressions: Toward a social functional account of face color in emotion communication. Emotion, 19(5), 799-807. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000485

Thorstenson, C.A., Pazda, A., & Lichtenfeld, S. (2019b). Facial blushing influences perceived embarrassment and related social functional evaluations. Cognition and Emotion June 23, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2019.1634004

Thorstenson, C.A., McPhetres, J., Pazda, A.D., & Young, S.G. (2021). The role of facial coloration in emotion disambiguation. Emotion, 22(7), 1604-1613. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000900

van den Berghe, P.L., & Frost, P. (1986). Skin color preference, sexual dimorphism and sexual selection: A case of gene-culture co-evolution? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 9(1), 87-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1986.9993516

Wagatsuma, H. (1967). The social perception of skin color in Japan. Daedalus, 96(2), 407-443. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027045

Walentowitz, S. (2008). Des êtres à peaufiner. Variations de la coloration et de la pigmentation du nouveau-né. In: J-P. Albert, B. Andrieu, P. Blanchard, G. Boëtsch, & D. Chevé (eds.) Coloris Corpus, (pp. 113-120). Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Wen, F., Zuo, B., Wu, Y., Sun, S., & Liu, K. (2014). Red is romantic, but only for feminine female faces: Sexual dimorphism moderates red effect on sexual attraction. Evolutionary Psychology, 12, 719–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491401200404

Wiedemann, D., Burt, D. M., Hill, R. A., & Barton, R. A. (2015). Red clothing increases perceived dominance, aggression and anger. Biology Letters, 11(5), 20150166. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0166

Yang, D., Li, X., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., & Meng, J. (2022). Skin color and attractiveness modulate empathy for pain: an event-related potential study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 780633. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.780633

Yip, A.W., & Sinha, P. (2002). Contribution of color to face recognition. Perception, 31(8), 995-1003. https://doi.org/10.1068/p3376

Young, S.G. (2015). The effect of red on male perceptions of female attractiveness: Moderation by baseline attractiveness of female faces. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45, 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2098

Young, S.G., Elliot, A.J., Feltman, R., & Ambady, N. (2013). Red enhances the processing of facial expressions of anger. Emotion, 13(3), 380–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032471

Zahan, D. (1974). White, Red and Black: Colour Symbolism in Black Africa. In: A. Portmann & R. Ritsema (Eds.) The Realms of Colour, Eranos, 41(1972), 365-395, Leiden: Eranos. https://doi.org/10.2307/1573594

Red or black clothes for dating profiles!

Interesting conjectures.