The original meaning of skin color

Hercules and Telephos. Fresco from Herculaneum, Museo Archeologico Nazionale.

Skin color is perceived through the lens of a mental algorithm that initially arose for gender recognition. People can tell whether a face is male or female even if the image is blurred and provides no other useful information than its hue and luminosity.

Today, skin color has a strong ethnic meaning. It differs mostly between people of different geographic origins, at least in modern Western societies. But that has not always been the case. In earlier societies, where people were overwhelmingly of local origin, skin color had a gendered meaning: it differed primarily between men and women.

Women are universally the fair sex (Frost and van den Berghe 1986). They are paler than men, who conversely are ruddier and browner. That sex difference was noticed in earlier times. Wherever the visual arts developed—ancient Egypt, the Greco-Roman world, early South and East Asia, Mesoamerica—female figures were depicted with a lighter hue and male figures with a darker one (Capart 1905, pp. 26-27; Eaverly 2013; Pallottino 1952, pp. 34, 45, 73, 76-77, 87, 93, 95, 105, 107, 115; Siepe 2004; Soustelle 1970, p. 130; Tegner 1992; Wagatsuma 1967). The same convention existed in literature. Greek writers and poets referred to women as “white” and men as “black” (Irwin 1974).

Hormonal causation

Male and female complexions differ because of differing concentrations of three pigments: melanin, hemoglobin, and carotene (Edwards and Duntley 1939). That sex difference is due to the action of the sex hormones: androgens in men and estrogens in women.

A hormonal causation has been shown by three lines of evidence:

Normal, castrated, and ovariectomized individuals. Castrated men have low androgen levels and are consequently very pale:

One of the outstanding characteristics of a human male castrate is the paleness of the skin. After treatment with androgenic hormone, however, the individual takes on a darker and more ruddy hue. This observation suggests that the skin of the castrate is deficient in melanin and blood, and that the androgenic hormone increases the content of these substances in the integument. (Edwards et al. 1941; see also Bischitz and Snell 1958)

Estrogens have a weaker effect on skin pigments, and that effect is further weakened by the other female hormone, progesterone (Edwards and Duntley 1949).

Sexual differentiation at puberty. At birth, both sexes are pale. The skin then darkens, but more so in girls, who actually become darker than boys. At puberty, that sex difference reverses, and girls become progressively lighter-skinned than boys (Note 1).

Digit ratio. This is the length of the index finger divided by the length of the ring finger. It provides a measure of the ratio of estrogens to androgens in the body’s tissues during development: the higher the ratio, the more the body’s tissues have been feminized; the lower the ratio, the more they have been masculinized.

Two digit ratio studies provide us with information on the sex difference in skin color and its hormonal causation. One study was done on adults. It showed that digit ratio correlates with lightness of skin in women but not in men. The correlation is also stronger for the left hand (Manning et al. 2004). We know that the left-hand ratio is a better measure of hormonal exposure later in life, as shown by a longitudinal study of children: digit ratio increases with age, and more so for the left hand than for the right hand (Trivers et al. 2006). Conversely, the right-hand ratio is a better measure of hormonal exposure before birth (Honekopp and Watson 2010).

The other study concerned children just before puberty, when girls are actually darker than boys. It showed that digit ratio correlates with darkness of skin in girls, but not in boys. The correlation is significant only for the right hand (Sitek et al. 2018).

Facultative pigmentation

Men and women differ not only in constitutive pigmentation but also in facultative pigmentation, i.e., the ability to tan. A man will tan more than a woman even when both are equally exposed to the sun (Harvey 1985).

In many cultures, facultative pigmentation is manipulated to lighten women’s skin even further, through sun shielding and sun avoidance. To that end, women will use parasols, wear long gloves and wide-brimmed hats, and confine their outdoor work to the early morning and the evening (Frost 2010, pp. 120-123).

Population differences

The sex difference in skin color is largest where humans are neither very dark nor very light. Where a medium color prevails, female skin has the most room to lighten without reaching maximum lightness, and male skin has the most room to darken without reaching maximum darkness (Frost 2007; Madrigal and Kelly 2007).

That is one reason why celebration of female whiteness reached its peak within the zone of medium complexions stretching from the Mediterranean through the Middle East and into South and East Asia (Eaverly 2013; Frost 2010, pp. 35-81, 156-157).

There, too, material culture first enabled women to beautify themselves by artificial means; in particular, white powders and other cosmetics to lighten their facial skin and to emphasize its lightness by darkening the regions of their lips and eyes (Russell 2003; Russell 2009; Russell 2010).

And there, too, non-material culture produced the first works of art, prose, and poetry, often on the theme of feminine beauty. Such works would fill the collective imagination with images of fair-skinned women (Cosquin 1922, pp. 1-9, 218-246; Irwin 1974, pp. 112-156; Tegner 1992).

Ishtar, a Babylonian goddess, Le Louvre

Noticeability?

How noticeable is the sex difference in skin color? In the best controlled spectrophotometric studies of skin reflectance, with Spanish and South Asian participants, boys and girls differ after puberty by about one and a half percentage points (Kalla 1973; Mesa 1983). By comparison, northern Europeans and West Africans differ by 25 to 30 percentage points (Robins 1991, Tables 7.1, 7.2).

Those measurements, however, are from the upper inner arm. The breasts and the buttocks have a much larger sex difference of 6 to 15 percentage points. The usual explanation is that women are more likely to conceal their breasts and buttocks from the sun. Yet those parts of the female body are lighter-colored not only because the skin has less melanin but also because it has less blood in its outer layers—a double causation that is hard to reconcile with the single cause of tanning (Edwards et al. 1939; Garn et al. 1956).

An alternative explanation is that the ratio of estrogens to androgens is higher in some parts of the female body than in others. The breasts and the buttocks have a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat in women, and fatty tissues are known to contain an enzyme (aromatase) that converts an androgen (androstenedione) into an estrogen (estrone) (Siiteri and MacDonald 1973). A thicker layer of fat produces more estrogen and thus feminizes the adjacent skin, making it softer, smoother, and fairer.

The hormonal explanation is supported by the parallels between age changes in skin reflectance and age changes in the subcutaneous fatty layer, which becomes thinner during childhood and thicker after puberty. The two traits also correlate with each other in adult women (Frost 2010, pp. 117-119; Mazess 1967; Parizkova 1977).

A cue for gender recognition

Whatever its actual magnitude, the sex difference in skin color seems to interest the human mind, particularly as a means to recognize male and female faces. A consensus has emerged that facial color is “a complex and crucial feature in facial processing. [...] Further, recent work has revealed consistent patterns of connected face and color selective cortical areas, possibly reflecting a shared overlap of visual processing between faces and color” (Thorstenson 2018; see also Samson et al. 2010).

Keep in mind that we have an innate ability to recognize faces. The existence of a hardwired mechanism is attested by prosopagnosia, a condition where a person seems normal and yet is no better at recognizing a face than any other object (Farah 1996; Pascalis and Kelly 2008; Zhu et al. 2009). At the other extreme is the “super-recognizer,” who is as good at face recognition as a prosopagnosic is bad (Russell et al. 2009). Such hardwiring should be no surprise. If a mental task is vital and occurs repeatedly in the same sort of way, it will become hardwired to shorten response time and eliminate learning time.

We are wired to use faces not only to distinguish individuals from each other but also to tell men and women apart. Some neurons specialize in male faces, others in female faces, and others in both (Baudouin and Brochard 2011; Bestelmeyer et al. 2008; Jacquet and Rhodes 2008; Little et al. 2005). An important cue is skin color (Bruce and Langton 1994; Hill, Bruce, and Akamatsu 1995; Russell and Sinha 2007; Russell et al. 2006; Tarr et al. 2001; Tarr, Rossion, and Doerschner 2002). Subjects can tell whether a face is male or female even if the image is blurred and provides no other useful information than its hue and luminosity (Tarr et al. 2001; Yip and Sinha 2002).

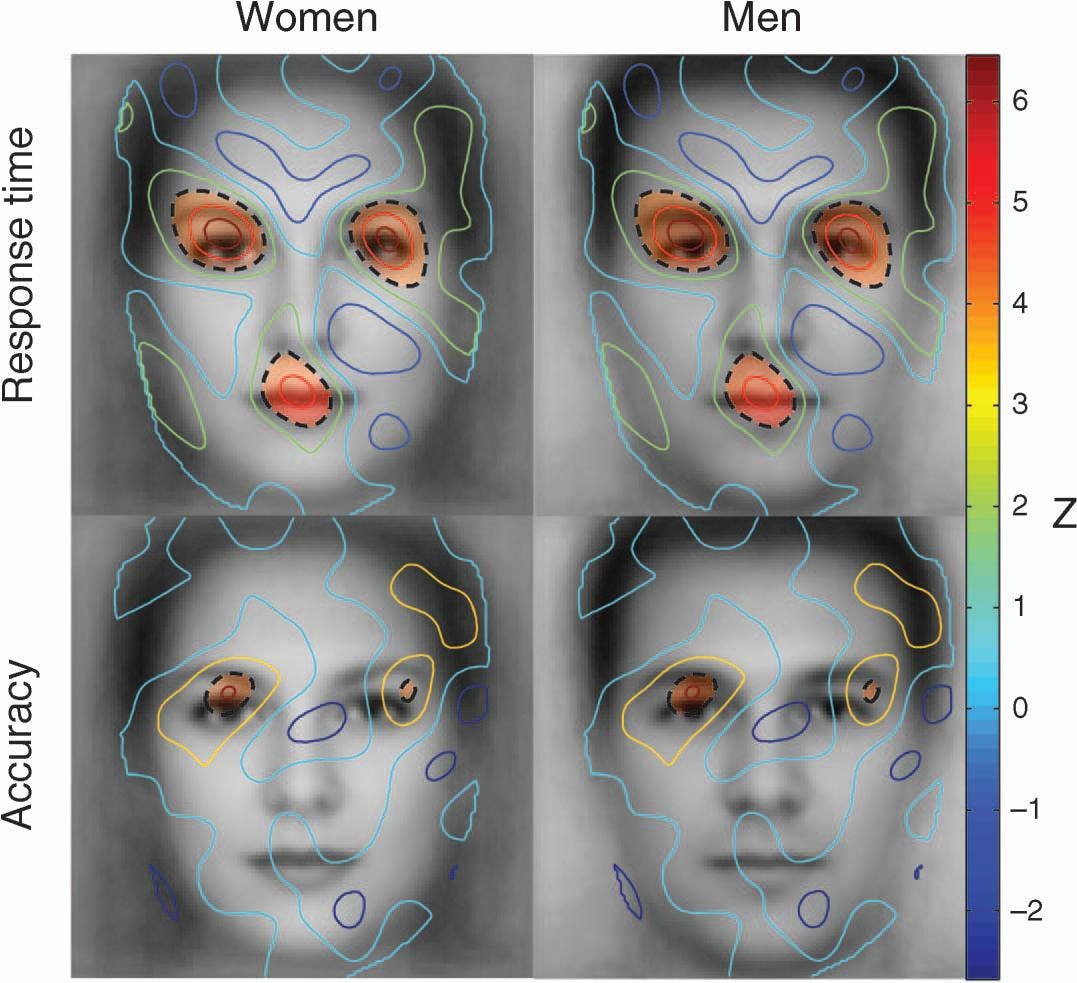

Hue is the brownness and ruddiness of facial skin, and luminosity is the relative difference between the lightness of facial skin and the darkness of the lip/eye area. Hue provides the fast channel for gender recognition. If the face is too far away or the lighting too dim, the mind will switch to the slower but more accurate channel of luminosity (Dupuis-Roy et al. 2009; Dupuis-Roy et al. 2019; Jones et al. 2015; Nestor and Tarr 2008a; Nestor and Tarr 2008b; Tarr et al. 2001; Tarr, Rossion, and Doerschner 2002).

The human mind thus associates darkness with men and lightness with women. This point has been further shown by three experiments with Dutch, Portuguese, and Turkish participants:

When asked to identify personal names by gender, the participants performed their task faster when male names were presented in black and female names in white than with the reverse.

When asked to classify briefly appearing black and white blobs by gender, the participants predominantly classified the former as male and the latter as female.

In an eye-tracking experiment, the participants showed longer observation and more frequent fixation when a dark object was associated with a male character and a light object with a female character (Semin et al. 2018).

Similar results were produced by a word-association test with Navajo participants: the color black was viewed as more potent and masculine and the color white as more active and feminine (Osgood 1960, p. 165).

Skin color is therefore perceived through the lens of a mental algorithm that initially arose for gender recognition. That algorithm may explain why lighter skin seems more feminine and darker skin more masculine.

Averaged faces of women and men from a French Canadian population. Female faces have higher luminosity and greater contrast between facial skin color and lip/eye area color. The orange colored pixels correspond to regions that were key to shorter response time and more accurate gender identification (Dupuis-Roy et al. 2009).

A cue for sexual attraction

Facial color is a cue not only for gender recognition but also for sexual attraction. This is suggested by several studies.

Male skin color that women prefer

Carrito et al. (2016) asked female participants to optimize the attractiveness of facial pictures by varying the skin's darkness and ruddiness. The women made the male faces darker and ruddier than the female faces

Stephen et al. (2012) allowed female participants to change the coloration of male facial photos to maximize perceived aggressiveness, dominance, or attractiveness. They associated high levels of male ruddiness with aggression, medium levels with dominance, and low levels with attractiveness. Perhaps, unlike the participants of the first study, they understood the term “attractive” in a purely aesthetic sense.

Perrett and Sprengelmeyer (2021) asked mainly female participants to select clothing that best matched a facial skin tone. They chose ‘cool’ blue hues for fair skin and ‘warm’ orange/red hues for tanned skin. There thus seems to be a tendency to associate redness with tanned skin and, hence, with the mix of blood and melanin that produces male skin tones.

Male skin color that women prefer, by menstrual cycle phase

Frost (1994) showed female participants pairs of facial pictures that differed slightly in color, and they had to choose the most pleasing one. When male faces were shown, the darker one was more strongly preferred by those women who were in the first two-thirds of their menstrual cycle than by those who were in the last third. During the first two-thirds of the cycle, estrogen is high in relation to progesterone (which acts as an anti-estrogen). During the last third, the ratio is reversed: estrogen is low in relation to progesterone. There was no cyclical effect among those women who were judging female faces or taking oral contraceptives.

Rupp et al. (2009) used MRI to measure the brain activity of female participants while they viewed pictures of male faces. They responded more strongly to masculinized male faces than to feminized ones, and the strength of their response correlated with the estrogen level across their menstrual cycle. In a personal communication, the lead author stated that the faces had been masculinized by making them darker and more robust in shape.

Skin color that infants prefer, by body fat content

Frost (1989) asked preschoolers to choose between two dolls that differed slightly in skin color. The children were also measured for their body fat content (body mass index and thickness of subcutaneous fat). Doll choice was the same for boys and girls. Below three years of age, however, children who chose the darker doll had significantly more body fat than those who chose the lighter doll. In that age range, estrogen is produced mostly in fatty tissue and not by the ovaries. Ovarian production later becomes relatively more important, first with the loss of baby fat by the third year of life and then with the pre-puberty increase in estrogen from the ovaries (Baird 1976; Klein et al. 1994).

Dolls have often been used to find out whether children prefer lighter or darker skin. In such studies, boys and girls show similar preferences up to six years of age (Renninger and Williams 1966; Williams and Roberson 1967; Williams and Rousseau 1971). Older ages bring a divergence between male and female preferences. When a group of American children, 3 to 8 years of age, were presented with a white-faced puppet and a brown-faced one, the latter puppet was more often chosen by girls than by boys, this finding being as true for European American children as for African American children (Asher and Allen 1969).

Two dolls that differ slightly in skin tone. Below three years of age, children who chose the darker doll had significantly more body fat than those who chose the lighter doll (Frost 1989).

A cue for gendered significations

Finally, facial color is a cue for other gender-related responses. Frost (2010, pp.149-152) studied these responses in a mono-ethnic context by interviewing elderly men and women in a rural French Canadian community of eastern Quebec. The interviewees described lighter skin in women as faible (weak) and délicat (delicate) and darker skin in men as fort (strong) and solide (solid). Within-gender differences were described in similar terms: a lighter-skinned person was doux (soft) and facile (easy-going), and a darker-skinned person dur (hard), prompt (quick-tempered), orgueilleux (arrogant), and malin (malicious).

Those findings are in line with cross-cultural and historical research on color symbolism: whiteness is generally associated with weakness and blackness with strength (Gergen 1967, p. 397; Osgood 1960, p. 165). For example, the ancient Greeks believed that a woman’s light complexion incarnated her “helplessness and need of protection” and a man’s dark complexion his “courage and the ability to fight well” (Irwin 1974, p. 121). A brave and strong man had a “black rump”; a coward a “white rump.” The same mental association was projected onto the internal organs and ultimately onto the soul. A “black heart” denoted strong emotions, a “white heart” indifference or a refusal to act. A coward had a “white liver” (Irwin 1974, pp. 129-155). The same mental association survives in our expression “lily-livered.”

If skin tones are rated solely on the weaker-to-stronger continuum, the darker tones would get a higher rating than the lighter ones. If, however, we rate them on another continuum, such as threatening vs. non-threatening, the result would be different. The perceptions are multidimensional, and we may mislead ourselves by choosing only one dimension.

Let’s take a closer look at American studies where preschoolers were asked to choose between two dolls that differed in skin color. Whatever their racial background, most chose the lighter-colored one when asked “Give me the doll that you like to play with” or “Give me the doll that is a nice doll” (Goodman 1946; Clark and Clark 1947).

Now, let’s turn to similar studies in non-American contexts:

Light skin was preferred by preschoolers in Japan, Italy, France, and Germany during the 1970s, when skin color had much less ethnic significance there than it does today (Best et al. 1975; Best et al. 1976; Iwawaki et al. 1978). The children associated a light-skinned figure (a person or an animal) with positive adjectives: “clean,” “pretty,” “kind,” “helpful,” “wonderful,” and “good.” Conversely, a dark-skinned figure was associated with negative adjectives: “naughty,” “dirty,” and “mean.”

A similar study shows preference for light skin by Mozambican children in Africa. In particular: (1) the preferred facial image was much lighter than the children’s own faces; (2) very light skin was preferred to fairly light skin; and (3) light-skin preference was strongest in the youngest age group (4-6 years). Light-skin preference became weaker with age, perhaps because ethnic self-awareness became stronger (Cruz 2012).

Preference for lighter skin does not follow a learning curve with increasing age (Best et al. 1975; Munitz et al. 1987); nor is it stronger in smarter children, who would be expected to learn faster (Williams et al. 1975a; Williams et al. 1975b; Williams and Rousseau 1971).

Is it possible that children prefer lighter skin simply because they perceive it as more feminine and, hence, more likely to provide loving care? And wouldn’t that preference be facilitated when they are asked to choose the nicer/prettier/kinder doll?

A mental association of light skin with femininity is supported by two unintended findings from the above study with French children. First, when preparing the lists of positive and negative adjectives, the American researchers incorrectly used robuste to translate “healthy.” Whereas most of the American children had associated “healthy” with the light-skinned figure, most of the French children associated robuste with the dark-skinned figure, perhaps because that word has masculine overtones of physical strength.

Second, French being a gendered language, the adjectives were sometimes presented in the masculine form and sometimes in the feminine form. Of the 12 positive adjectives, 3 were feminine, 3 were masculine, and 6 had no clear gender. Of the 12 negative adjectives, 3 were feminine, 5 were masculine, and 4 had no clear gender. Of the adjectives chosen by over 70% of the children only 1 out of 5 positive ones were masculine whereas 2 out of 3 negative ones were (Best et al. 1975). The children thus associated light skin with femininity by choosing adjectives that were feminine not only semantically but also grammatically.

Origins in the Kindchenschema

A woman resembles an infant in her look, feel, and voice. In both cases, the complexion is lighter than the adult male’s (Grande et al. 1994; Kalla 1973; Post et al. 1976; Visscher et al. 2017). The adult female also has a smaller nose and chin, smoother, more pliable skin, and a higher vocal pitch. Those traits are what Konrad Lorenz dubbed the Kindchenschema, a set of visual, tactile, and auditory cues that identify a human infant to an adult, who then feels less aggressive and more willing to provide care and nurturance (Frost 2010, pp. 134-135; Lorenz 1971, pp. 154-164; Wickler 1973, pp. 255-265).

A lighter skin identifies an infant as an infant not only to humans but also to nonhuman primates, particularly langurs, baboons, and macaques. Their skin is initially pink and then darkens, becoming almost black in adulthood. A mother thus has a means to find wayward offspring. As their skin darkens with age she loses interest in seeking and holding them (Alley 1980; Alley 2014; Booth 1962; Jay 1962).

In humans, the infant’s pink skin is especially noticeable in societies where the adult is much darker. A new Kenyan mother may tell her neighbors to come and see her mzungu, i.e., “European” (Walentowitz 2008). When Zambian girls were asked to describe how Africans look, some wrote: “At birth African children are born like Europeans, but after a few months the color changes to the color of an African” (Powdermaker 1956).

The newborn’s light color is often attributed to a previous spirit life:

There is a rather widespread concept in Black Africa, according to which human beings, before “coming” into this world, dwell in heaven, where they are white. For, heaven itself is white and all the beings dwelling there are also white. Therefore the whiter a child is at birth, the more splendid it is. In other words, at that particular moment in a person's life, special importance is attached to the whiteness of his colour, which is endowed with exceptional qualities. (Zahan 1974, p. 385)

An ethnographer of African societies makes the same point: “black is thus the color of maturity [...] White on the other hand is a sign of the before-life and the after-life: the African newborn is light-skinned and the color of mourning is white kaolin” (Maertens 1978, p. 41).

As long as the skin is light-colored, a newborn African remains soft and vulnerable, and hence at risk of returning to heaven.

According to the same concept, it is also claimed that a newborn baby is not only white but also a soft being during the time between his birth and his acceptance into the society. Furthermore, during this entire period, he is not considered a real person, and this may go so far that parents and society may do away with him at will for reasons that are peculiar to each social group. Having been done away with, these beings are considered to return automatically to the place where they came from, that is, to heaven. (Zahan 1974, p. 386-387)

Newborn African American (Wikicommons)

The lighter skin of women thus seems to be the final stage of an evolutionary trajectory that began with the lighter skin of nonhuman primate infants:

In nonhuman primates, the pink skin of newborn individuals initially had no mental or behavioral significance. It was an accident of birth, there being no need for dark pigmentation in the womb.

Adults recognized this visible trait as being specific to infants, and in time it was incorporated into the Kindchenschema. Certain mental and behavioral responses to it became hardwired, especially in the minds of females. Those responses could be overridden in the minds of strange males that would sometimes invade the group and kill the young (Alley 1980).

Natural selection favored those infants that remained lighter-skinned until they no longer had to be cared for. The infant coloration thus persists longer in primate species whose infants remain helpless for a longer time.

In humans, a combination of slower maturation, higher paternal investment, and longer-lasting pair bonds made women more vulnerable to male neglect and aggression, thus putting them in a situation like that of infants and causing them to mimic the same Kindchenschema.

The sex difference in human skin color has no true antecedents in other primates, but there is an analogous sex difference. In seven of the eight primate species where the male and the female differ in coat color, the female has the infant’s light coloration. Interestingly, five of the seven species (63%) are monogamous, whereas only 18% of all primate species are (Blaffer-Hrdy and Hartung 1979). By mimicking the infant’s coloration, the female may improve her chances of survival in a family environment that increases her vulnerability to neglect (because she depends more on male provisioning) and to male aggression (because she cohabits longer and more continuously with the male). Such mimicry seems to have shaped much of mammalian sexuality, notably behaviors like cuddling, murmuring, nipple sucking, and mouth licking (Wickler 1973, pp. 163-185).

The above evolutionary scenario was first proposed by ethologist Russell Guthrie:

I believe the sexual differences in skin color resulted from female whiteness being selected for because it is opposite the threat coloration, although the selection pressures may have been rather mild. Light skin seems to be more paedomorphic, since individuals of all races tend to darken with age. Even in the gorilla, the most heavily pigmented of the hominoids, the young are born with very little pigment. [...] Thus, a lighter colored individual may present a less threatening, more juvenile image. (Guthrie 1970).

By projecting a childlike image, the lighter skin of women serves not to increase male sexual arousal but rather to alter it. Guthrie’s hypothesis is supported by an eye-tracking study. Initially, the male participants were shown pictures of women and asked to rate their attractiveness. The lighter-skinned women were not rated as more attractive than the darker-skinned ones. The men’s eye movements were then tracked, and it was found that the women with lighter skin were viewed longer (Garza et al. 2016). The longer duration seems to indicate not so much a higher level of interest as a more sustained interest with a slower rise and fall.

Such interest is shown not only by observation length but also by pupil dilation. In a Japanese experiment, pupil size was measured while the female participants were looking at images of female faces. The dilation of the observer’s pupils correlated significantly with the lightness of the observed facial color (Kuraguchi and Kanari 2021).

Facial color and transient emotions

Anger

Facial color can change briefly, such as during outbursts of anger. An angry man will turn red in the face and thus seem more intimidating. When, at the 2004 Olympic Games, opponents were randomly assigned red or blue uniforms for boxing, taekwondo, Greco-Roman wrestling, and freestyle wrestling, they were significantly likelier to win if they wore red uniforms. The effect was strong: red winners outnumbered blue winners in 16 out of 21 rounds, and only 4 rounds had the reverse outcome (Hill and Barton 2005). That finding was further investigated by asking men and women to identify the color of words on a computer screen. Men took significantly longer to answer when the words were red (Ioan et al. 2007). Other studies have shown that facial color helps an observer distinguish between emotional states that share similar facial expressions, such as anger versus disgust, surprise versus fear, and sadness versus happiness (Thorstenson et al. 2019a; Thorstenson et al. 2022).

Fright

Just as a face will turn red in anger, it will also turn pale with fright. The desired effect on the observer is now the reverse: to appease and de-escalate. A questionnaire study found that pallor is associated with fear and a low level of anger. When the respondents were asked to rate their propensity for turning pale in everyday situations, the highest scores came from those who feared blood and injury. The mean score was higher for women than for men (Drummond 1997).

Embarrassment

Finally, a face can turn red with embarrassment, i.e., “blushing.” The blushing response is not a form of appeasement, being in fact often associated with high levels of controlled anger (Drummond 1997). Charles Darwin attributed it to shyness, shame, or modesty, the underlying cause being “self-attention in relation to moral conduct” (Darwin 1872, p. 326). In most cases, the reddening is confined to the face, ears, and neck. It also seems to be heritable. Darwin cited the case of a father, mother, and ten children, “all of whom, without exception, were prone to blush to a most painful degree” (Darwin 1872, p. 312). A series of controlled experiments has confirmed that the cause is embarrassment due to a social transgression. If a person blushes while making an apology, the observer will more likely perceive it as sincere and forgive the transgressor (Thorstenson et al. 2019b).

Conclusion

Today, skin color has a primarily ethnic meaning. It had other meanings in the past, apparently even our nonhuman past. In many primate species, the infant is light-skinned, and this coloration not only identifies the infant as an infant but also induces feelings of caring and protectiveness in the adult observer. At some point in human evolution, the same coloration was acquired by women, along with other visual, audible, and tactile characteristics of the infant. Skin color thus became a means to distinguish women from men, with lighter skin being unconsciously perceived as feminine and darker skin as masculine. Such perceptions would influence an observer’s behavioral and emotional state when interacting with a man, a woman, or a young child.

In modern Western societies, those gendered perceptions have been so eclipsed by ethnic ones that they remain largely unconscious. But they are still part of conscious experience elsewhere in the world.

Notes

1. The literature is reviewed by van den Berghe and Frost (1986). The best controlled studies are those by Kalla (1973) on South Asians, Kalla and Tiwari (1970) on Tibetans, and Mesa (1983) on Spaniards. After middle age, the sex difference in skin color tends to disappear:

After middle life, the amount of estrogenic and androgenic hormones begins to diminish, and the skin of old age begins to appear. […] there is deposited in the epidermis more pigment than in youth, and the skin becomes diffusely brown, and in those who have little natural pigment it becomes grey and pasty. In women, hair grows on the face, and finally male and female skin are nearly identical in essential characteristics. (Bancroft 1944, p. 61)

References

Alley, T. R. (1980). Infantile colouration as an elicitor of caretaking behaviour in Old World primates. Primates 21(3): 416-429. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02390470

Alley, T.R. (2014[1986]). An ecological analysis of the protection of primate infants. In: V. McCabe and G.J. Balzano (eds.) Event Cognition: An Ecological Perspective. Routledge.

Asher, S.R. and Allen, V.L. (1969). Racial preference and social comparison processes. Journal of Social Issues 25(1): 157-166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1969.tb02584.x

Baird, D.T. (1976). Oestrogens in clinical practice. In: J.A. Loraine and E. Trevor Bell (eds.) Hormone assays and their clinical application (p. 408). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Bancroft, I.R. (1944). Hormones and the skin. California and Western Medicine 61(2): 60-62.

Baudouin, J.-Y., and Brochard, R. (2011). Gender-based prototype formation in face recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 37(4): 888-898. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022963

Best, D.L., Field, J.T., and Williams, J.E. (1976). Color bias in a sample of young German children. Psychological Reports 38(3): 1145-1146. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1976.38.3c.1145

Best, D.L., Naylor, C.E., and Williams, J.E. (1975). Extension of color bias research to young French and Italian children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 6(4): 390-405. https://doi.org/10.1177/002202217564003

Bestelmeyer, P.E.G., Jones, B.C., DeBruine, L.M., Little, A.C., Perrett, D.I., Schneider, A., Welling, L.L.M., and Conway, C.A. (2008). Sex-contingent face aftereffects depend on perceptual category rather than structural encoding. Cognition 107(1): 353-365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.07.018

Bischitz, P., and Snell, R. (1958). Effect of testosterone and orchidectomy on the activity of the melanocytes in the skin. Nature 181: 187-188. https://doi.org/10.1038/181187b0

Blaffer-Hrdy, S. and Hartung, J. (1979). The evolution of sexual dichromatism among primates. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 50(3): 450.

Booth, C. (1962). Some observations on behavior of Cercopithecus monkeys. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 102(2): 477-487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13654.x

Bruce, V., and Langton, S. (1994). The use of pigmentation and shading information in recognising the sex and identities of faces. Perception 23(7): 803-822. http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/p230803

Capart, J. (1905). Primitive Art in Egypt. London: H. Grevel.

Carrito, M.L., dos Santos, I.M.B., Lefevre, C.E., Whitehead, R.D., da Silva, C.F., and Perrett, D.I. (2016). The role of sexually dimorphic skin colour and shape in attractiveness of male faces. Evolution and Human Behavior 37(2): 125-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.09.006

Clark, K.B. and Clark, M.P. (1947). Racial identification and preference in Negro children. In: T.M. Newcomb and E.L. Hartley (eds.) Readings in Social Psychology, (pp. 169-178). New York: Henry Holt.

Cosquin, E. (1922). Les contes indiens et l'Occident. Paris: Librairie ancienne Honoré Champion.

Cruz, V. (2012). Age, gender and social class influences on skin colour preferences among Mozambican children. Journal of Psychology in Africa 27(2): 139-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2012.10874532

Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: John Murray.

Drummond, P.D. (1997). Correlates of facial flushing and pallor in anger - provoking situations. Personality and Individual Differences 23(4): 575-582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00077-9

Dupuis-Roy, N., Faghel-Soubeyrand, S., and Gosselin, F. (2019). Time course of the use of chromatic and achromatic facial information for sex categorization. Vision Research 157: 36-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2018.08.004

Dupuis-Roy, N., Fortin, I., Fiset, D., and Gosselin, F. (2009). Uncovering gender discrimination cues in a realistic setting. Journal of Vision 9(2): 10, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1167/9.2.10

Eaverly, M.A. (2013). Tan Men/Pale Women. Color and Gender in Archaic Greece and Egypt, a Comparative Approach. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.3080238

Edwards, E.A., and Duntley, S.Q. (1939). The pigments and color of living human skin. American Journal of Anatomy 65(1): 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1002/aja.1000650102

Edwards, E.A., and Duntley, S.Q. (1949). Cutaneous vascular changes in women in reference to the menstrual cycle and ovariectomy. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 57(3): 501-509. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(49)90235-5

Edwards, E.A., Hamilton, J.B., Duntley, S.Q., and Hubert, G. (1941). Cutaneous vascular and pigmentary changes in castrate and eunuchoid men. Endocrinology 28(1): 119-128. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-28-1-119

Farah, M. J. (1996). Is face recognition 'special'? Evidence from neuropsychology. Behavioural Brain Research 76(1-2): 181-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-4328(95)00198-0

Frost, P. (1989). Human skin color: the sexual differentiation of its social perception. Mankind Quarterly 30: 3-16. http://doi.org/10.46469/mq.1989.30.1.1

Frost, P. (1994). Preference for darker faces in photographs at different phases of the menstrual cycle: Preliminary assessment of evidence for a hormonal relationship. Perceptual and Motor Skills 79(1): 507-14. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1994.79.1.507

Frost, P. (2007). Comment on Human skin-color sexual dimorphism: A test of the sexual selection hypothesis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 133(1): 779-781. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20555

Frost, P. (2010). Femmes claires, hommes foncés. Les racines oubliées du colorisme. Quebec City: Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 202 p. https://www.pulaval.com/livres/femmes-claires-hommes-fonces-les-racines-oubliees-du-colorisme

Garn, S.M., Selby, S., and Crawford, M.R. (1956). Skin reflectance studies in children and adults. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 14:101-117. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330140123

Garza, R., Heredia, R.R., and Cieslicka, A.B. (2016). Male and female perception of physical attractiveness. An eye movement study. Evolutionary Psychology 14(1): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1474704916631614

Gergen, K.J. (1967). The significance of skin color in human relations. Daedalus 96: 390-406. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027044

Goodman, M.E. (1946). Evidence concerning the genesis of interracial attitudes. American Anthropologist 48(4): 624-630. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1946.48.4.02a00080

Grande, R., Gutierrez, E., Latorre, E., and Arguelles, F. (1994). Physiological variations in the pigmentation of newborn infants. Human Biology 66(3): 495-507. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41465000

Guthrie, R.D. (1970). Evolution of human threat display organs. In: T. Dobzhansky, M.K. Hecht, and W.C. Steere (eds.) Evolutionary Biology 4: 257-302. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts.

Harvey, R. G. (1985). Ecological factors in skin color variation among Papua New Guineans, American Journal of Physical Anthropology 66(4): 407-416. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330660409

Hill, H., V. Bruce, and Akamatsu, S. (1995). Perceiving the sex and race of faces: The role of shape and colour. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 261(1362): 367-373. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1995.0161

Hill, R., and Barton, R. (2005). Red enhances human performance in contests. Nature 435: 293. https://doi.org/10.1038/435293a

Hönekopp, J. and Watson, S. (2010). Meta-analysis of digit ratio 2D:4D shows greater sex difference in the right hand. American Journal of Human Biology 22(5): 619-630. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.21054

Ioan, S., Sandulache, M., Avramescu, S., Ilie, A., and Neacsu, A. (2007). Red is a distractor for men in competition. Evolution and Human Behavior 28: 285-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.03.001

Irwin, E. (1974). Colour Terms in Greek Poetry. Toronto: Hakkert.

Iwawaki, S., Sonoo, K., Williams, J.E., and Best, D.L. (1978). Color bias among young Japanese children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 9(1): 61-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002202217891005

Jaquet, E., and Rhodes, G. (2008). Face aftereffects indicate dissociable, but not distinct, coding of male and female faces. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 34(1): 101-112. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.34.1.101

Jay, P.C. (1962). Aspects of maternal behavior among langurs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 102(2): 468-476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb13653.x

Jones, A.L., Russell, R., and Ward, R. (2015). Cosmetics alter biologically-based factors of beauty: evidence from facial contrast. Evolutionary Psychology 13(1): https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491501300113

Kalla, A.K. (1973). Ageing and sex differences in human skin pigmentation. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie 65(1): 29-33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25756080

Kalla, A.K., and Tiwari, S.C. (1970). Sex differences in skin colour in man. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae 19(3): 472-476. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1120962300014876

Klein, K.O., Baron, J., Colli, M.J., McDonnell, D.P., and Cutler, G.B. Jr. (1994). Estrogen levels in childhood determined by an ultrasensitive recombinant cell bioassay. Journal of Clinical Investigation 94(6): 2475-2480. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI117616 .

Kuraguchi, K. and Kanari, K. (2021). Enlargement of female pupils when perceiving something cute. Scientific Reports 11: 23367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02852-5

Little, A.C., DeBruine, L.M., and Jones, B.C. (2005). Sex-contingent face after-effects suggest distinct neural populations code male and female faces. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B 272(1578): 2283-2287. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3220

Lorenz, K. (1971). Studies in Animal and Human Behaviour, vol. 2. London: Methuen & Co.

Madrigal, L., and Kelly, W. (2006). Human skin-color sexual dimorphism: A test of the sexual selection hypothesis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 132(3): 470-482. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20453

Maertens, J-T. (1978). Le dessein sur la peau. Essai d'anthropologie des inscriptions tégumentaires, Ritologiques I. Paris: Aubier Montaigne.

Manning, J.T., Bundred, P.E., and Mather, F.M. (2004). Second to fourth digit ratio, sexual selection, and skin colour. Evolution and Human Behavior 25(1): 38-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-5138(03)00082-5

Mazess, R.B. (1967). Skin color in Bahamian Negroes. Human Biology 39(2): 145-154.

McGovern, J.R. (1968). The American woman's pre-World War I freedom in manners and morals. Journal of American History 55(2): 315-333. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1899561

Mesa, M.S. (1983). Analyse de la variabilité de la pigmentation de la peau durant la croissance. Bulletin et mémoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris. t. 10 série 13, 49-60. https://doi.org/10.3406/bmsap.1983.3882

Munitz, S., Priel, B., and Henik, A. (1987). Color, skin color preferences and self color identification among Ethiopian and Israeli born children. In: M. Ashkenazi and A. Weingrod (eds.) Ethiopian Jews and Israel, (pp. 74-84), New Brunswick (U.S.A.): Transaction Books

Nestor, A., and Tarr, M.J. (2008a). The segmental structure of faces and its use in gender recognition. Journal of Vision 8(7): 7, 1-12, http://journalofvision.org/8/7/7/ https://doi.org/10.1167/8.7.7

Nestor, A., and Tarr, M.J. (2008b). Gender recognition of human faces using color. Psychological Science 19(12): 1242-1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02232.x

Osgood, C.E. (1960). The cross-cultural generality of visual-verbal synesthetic tendencies. Behavioral Science 5(2): 146-169. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830050204

Pallottino, M. (1952). Etruscan Painting. Lausanne: Skira.

Parizkova, J. (1977). Body Fat and Physical Fitness. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Pascalis, O., and Kelly, D.J. (2008). Face processing. In: M. Haith and J. Benson (eds.) Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development, (pp. 471-478), Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-012370877-9.00059-1

Perrett, D.I., and Sprengelmeyer, R. (2021). Clothing aesthetics: consistent colour choices to match fair and tanned skin tones. i-Perception 12(6): 204166952110533. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/20416695211053361

Post, P.W., Krauss, A.N., Waldman, S., and Auld, P.A.M. (1976). Skin reflectance of newborn infants from 25 to 44 weeks gestational age. Human Biology 48(3): 541-557. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41462904

Powdermaker, H. (1956). Social change through imagery and values of teen-age Africans in Northern Rhodesia. American Anthropologist 58(5): 783-813 https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1956.58.5.02a00030

Renninger, C.A. and Williams, J.E. (1966). Black-white color connotations and racial awareness in preschool children. Perceptual and Motor Skills 22(3): 771-785. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1966.22.3.771

Robins, A.H. (1991). Biological perspectives on human pigmentation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rupp, H.A., James, T.W., Ketterson, E.D., Sengelaub, D.R., Janssen, E., and Heiman, J.R. (2009). Neural activation in women in response to masculinized male faces: mediation by hormones and psychosexual factors. Evolution and Human Behavior 30(1): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.08.006

Russell, R. (2003). Sex, beauty, and the relative luminance of facial features. Perception 32(9): 1093-1107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/p5101

Russell, R. (2009). A sex difference in facial pigmentation and its exaggeration by cosmetics. Perception 38(8): 1211-1219. https://doi.org/10.1068/p6331

Russell, R. (2010). Why cosmetics work. In: R.B. Adams Jr., N. Ambady, K. Nakayama, and S. Shimojo (eds.) The Science of Social Vision, (pp. 186-203). New York: Oxford.

Russell, R., Duchaine, B., and Nakayama, K. (2009). Super-recognizers: People with extraordinary face recognition ability. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 16(2): 252-257. https://dx.doi.org/10.3758%2FPBR.16.2.252

Russell, R. and Sinha, P. (2007). Real-world face recognition: The importance of surface reflectance properties. Perception 36(9): 1368-1374. http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/p5779

Russell, R., Sinha, P., Biederman, I., and Nederhouser, M. (2006). Is pigmentation important for face recognition? Evidence from contrast negation. Perception 35: 749-759. https://doi.org/10.1068%2Fp5490

Samson, N., Fink, B., and Matts, P.J. (2010). Visible skin condition and perception of human facial appearance. International Journal of Cosmetic Science 32(3): 167-184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2494.2009.00535.x

Semin, G.R., Palma, T., Acartürk, C., and Dziuba, A. (2018). Gender is not simply a matter of black and white, or is it? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences 373(1752):20170126. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0126

Siepe, F. (2004). Farben des Eros. Marginalien zur Kulturgeschichte der Liebes- und Schönheitswahrnehmung in Antike und christlichem Abendland. Marburg: Kline.

Siiteri, P.K. and MacDonald, P.C. (1973). Role of extraglandular estrogen in human endocrinology. In: S.R. Geiger (ed.), Handbook of Physiology, vol. II, Part 1, (pp. 615-629). Washington D.C.: American Physiology Society, Section 7.

Sitek, A., Koziel, S., Kasielska-Trojan, A., and Antoszewski, B. (2018). Do skin and hair pigmentation in prepubertal and early pubertal stages correlate with 2D:4D? American Journal of Human Biology 30(6): e12631. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23183

Soustelle, J. (1970). The Daily Life of the Aztecs. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Stephen, I.D., Oldham, F.H., Perrett, D.I., and Barton, R.A. (2012). Redness enhances perceived aggression, dominance and attractiveness in men's faces. Evolutionary Psychology 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491201000312

Tarr, M.J., Kersten, D., Cheng, Y., and Rossion, B. (2001). It's Pat! Sexing faces using only red and green. Journal of Vision 1(3): 337, 337a. https://doi.org/10.1167/1.3.337

Tarr, M. J., Rossion, B., and Doerschner, K. (2002). Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: Behavioral and neural correlates of face sexing using color. Journal of Vision 2(7): 598, 598a, http://journalofvision.org/2/7/598/ https://doi.org/10.1167/2.7.598 .

Tegner, E. (1992). Sex differences in skin pigmentation illustrated in art. The American Journal of Dermatopathology 14(3): 283-287. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000372-199206000-00016

Thorstenson, C.A. (2018). The social psychophysics of human face color: Review and recommendations. Social Cognition 36(2): 247-273. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2018.36.2.247

Thorstenson, C.A., Pazda, A.D., Young, S.G., and Elliot, A.J. (2019a). Face color facilitates the disambiguation of confusing emotion expressions: Toward a social functional account of face color in emotion communication. Emotion 19(5): 799-807. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000485

Thorstenson, C.A., Pazda, A., and Lichtenfeld, S. (2019b). Facial blushing influences perceived embarrassment and related social functional evaluations. Cognition and Emotion June 23, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2019.1634004

Thorstenson, C.A., McPhetres, J., Pazda, A.D., and Young, S.G. (2022). The role of facial coloration in emotion disambiguation. Emotion 22(7): 1604-1613. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000900

Trivers, R., Manning, J., and Jacobson, A. (2006). A longitudinal study of digit ratio (2D:4D) and other finger ratios in Jamaican children. Hormones and Behavior 49(2): 150-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.05.023

van den Berghe, P. L. and P. Frost. (1986). Skin color preference, sexual dimorphism, and sexual selection: A case of gene-culture co-evolution? Ethnic and Racial Studies 9(1): 87-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1986.9993516

Visscher, M.O., Burkes, S.A., Adams, D.M., Hammill, A.M., and Wickett, R.R. (2017). Infant skin maturation: preliminary outcomes for color and biochemical properties. Skin Research & Technology 23(4): 545-551. https://doi.org/10.1111/srt.12369

Wagatsuma, H. (1967). The social perception of skin color in Japan. Daedalus 96(2): 407-443. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027045

Walentowitz, S. (2008). Des êtres à peaufiner. Variations de la coloration et de la pigmentation du nouveau-né. In: J-P. Albert, B. Andrieu, P. Blanchard, G. Boëtsch, and D. Chevé (eds.) Coloris Corpus, (pp. 113-120). Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Wickler, W. (1973). The Sexual Code. Garden City: Anchor.

Williams, J.E., Boswell, D.A., and Best, D.L. (1975a). Evaluative responses of preschool children to the colors white and black. Child Development 46(2): 501-508. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128148

Williams, J.E., Best, D.L., Boswell, D.A., Mattson, L.A., and Graves, D.J. (1975b). Preschool racial attitude measure II. Educational and Psychological Measurement 35(1): 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447503500101

Williams, J.E. and Roberson, J.K. (1967). A method for assessing racial attitudes in preschool children. Educational and Psychological Measurement 27(3): 671-689. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446702700310

Williams, J.E. and Rousseau, C.A. (1971). Evaluation and identification responses of Negro preschoolers to the colors black and white. Perceptual and Motor Skills 33(2): 587-599. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1971.33.2.587

Yip, A.W., and Sinha, P. (2002). Contribution of color to face recognition. Perception 31(8): 995-1003. https://doi.org/10.1068/p3376

Zahan, D. (1974). White, Red and Black: Colour Symbolism in Black Africa. In A. Portmann and R. Ritsema (Eds.) The Realms of Colour, Eranos 41 (1972): 365-395, Leiden: Eranos. https://doi.org/10.2307/1573594

Zhu, Q., Song, Y., Hu, S., Li, X., Tian, M., Zhen, Z., Dong, Q., Kanwisher, N., and Liu, J. (2009). Heritability of the specific cognitive ability of face perception. Current Biology 20(2): 137-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.067

Mind blowing as always.

I've read recently that European females have darker skin tones than European males. This seems even to be linked to Wikipedia currently. This seems a bit odd, because observationally I'd say European females are observably lighter in tone. I'm open to this being maybe by some cultural/societal thing (such as men working more outside, practicing more sports, women avoiding sun exposure due to beauty standards, and so on), but the literature seems not very specific about this specifically, as far as I could find.

What is your take about this specifically since you much more informed than I about the literature and overall subject?