Was the Roman Empire eugenic?

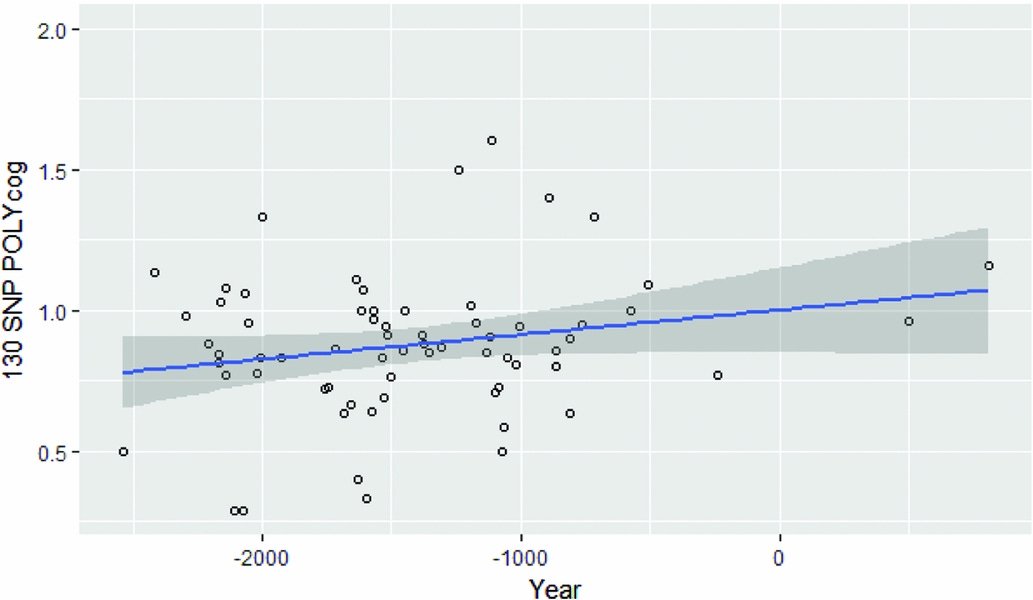

Rise, fall, and renewed rise of mean cognitive ability in central Italy (Piffer et al, 2023, Figure 1)

Ancient DNA is revealing the cognitive evolution of ancient Rome. Mean cognitive ability rose from the Neolithic to the time of the Republic, fell during the Imperial Era, and then rose again during Late Antiquity. What did Christian Imperial Rome do right that the Pagan one did wrong?

The Roman Empire was anything but eugenic. We actually have concrete data on this point, specifically DNA from human remains. Ancient DNA can reveal not only the physical appearance of long-dead people but also their capacity for intelligence—what we call “cognitive ability.” Researchers have identified thousands of genes whose alleles are associated with variation in that mental trait (Lee et al., 2018). By finding out which alleles are present, we can make an estimate of cognitive ability that strongly correlates with performance on standardized mathematics, reading, and science tests (r = 0.8) and, on a group level, with mean population IQ (r = 0.9) (Piffer, 2019).

A team led by Davide Piffer looked at DNA from 127 individuals who lived in central Italy during a period extending from the Neolithic to contemporary times. His team found that mean cognitive ability rose from the Neolithic to the time of the Roman Republic, then fell during the Imperial Era, and finally rose again from Late Antiquity to medieval times (Piffer et al., 2023).

Another research team, led by Michael Woodley of Menie, found a steady rise in mean cognitive ability among Europeans and Central Asians from 4,560 to 1,210 years ago. The researchers had DNA from 102 individuals, mainly from the early Bronze to early Iron ages, but none from the Imperial Era of Rome (Woodley of Menie et al., 2017).

In sum, mean cognitive ability steadily rose once humans began to farm and congregate in villages and towns, probably because their minds had to cope with a growing range of cognitive demands. This trend then reversed with the creation of the Roman Empire. Why?

Rise of mean cognitive ability in Europe and Central Asia (Woodley of Menie et al., 2017, Figure 1)

Relaxation of natural selection? Or rise of Christianity?

One explanation is that life became so comfortable that cognitive ability no longer mattered for survival and reproduction. Because natural selection had ceased to operate, the average Roman became less intelligent from one generation to the next. Hard times then returned with the onset of Late Antiquity, and so did natural selection.

This explanation rests on two assumptions:

First, life became so much better during the Imperial Era that natural selection no longer favored the more intelligent over the less intelligent. This assumption is inconsistent, however, with estimates of life expectancy: “Almost all ancient historians now accept the view, originally propounded by Keith Hopkins in 1966, that for the general population, average Roman life expectancy at birth is likely to have lain in a range from 20 to 30 years” (Frier, 2001, p. 144). Natural selection seems to have had plenty of room to do its work.

Second, life then got so bad during Late Antiquity that natural selection again favored the more intelligent. This assumption covers the period from 300 to 700 CE. Using skeletal data, Jongman et al. (2019) concluded that physical health actually improved after 300 and worsened only after 550. That trend is consistent with the historical record. Roman civilization did not end with the abdication of Romulus Augustulus in 476. In fact, his barbarian successors, Odoacer and Theodoric, were good rulers. The end really came with the Gothic War (535-554) and the Plague of Justinian (541-549).

Late Antiquity had one thing that lasted throughout its duration, namely Christianity. The Christian faith was legalized throughout the Empire in 313 and became the State religion in 380. Is it a coincidence that the same period saw a renewed upward trend in mean cognitive ability? The Church intervened extensively in human reproduction, particularly by formalizing marriage while vilifying divorce and extramarital relationships. Could that societal change explain why mean cognitive ability rose after 300 CE?

To test the above two explanations—hard times versus Christianity—we could split the Late Antiquity data into two sub-periods: the years 300 to 550 and the years 550 to 700. If mean cognitive ability rose only during the second half, we could attribute that rise to hard times. Otherwise, Christianity would be the likelier cause.

Physical health over time in the Roman Empire, as shown by skeletal data (Jongman et al., 2019, Figure 4)

Disconnect between material success and reproductive success?

If Christianity brought a rise in mean cognitive ability during Late Antiquity, why did Paganism bring a decline during the Imperial Era?

Briefly put, material success was no longer translated into reproductive success. The upper classes were not passing on their higher cognitive ability to the next generation, either because they were having fewer children or because they were having them with concubines of lower cognitive ability. This explanation is not wholly at odds with the dolce vita one: the pursuit of a more comfortable life became less dependent on having a family to fall back on. The upper classes had slaves to care for their material and sexual needs.

Rome’s cognitive decline thus had three causes:

A decline in fertility and family formation among the upper classes (Caldwell, 2004; Hopkins, 1965; Roetzel, 2000, p. 234; Sullivan, 2009, pp. 27-28, 35-38).

An increase in female hypergamy, often by freed slaves, with a corresponding decrease in the reproductive importance of upper-class women (Perry, 2013).

An increase in the slave population, particularly foreign slaves (Harris, 1999), with a corresponding disruption of local cognitive evolution. To the extent that the upper classes had surplus individuals, they could no longer move down into lower-class niches and eventually replace the lower classes, as would happen in late medieval and post-medieval England (Clark, 2007; 2009; 2023). Such niches were deemed fit only for slaves (Frost, 2022).

At first thought, the cognitive decline during the Imperial Era seems counterintuitive. This was when the Empire was expanding and building roads, aqueducts, and fortifications. Much less had been achieved during the time of the Republic. How do we explain the apparent contradiction?

Answer: the Empire could mobilize far more human resources to achieve its goals. Centralized power was able to do more with a large population than with a small one. Economies of scale became possible, and labor could be put to specialized uses, including the intellectual labor of the “smart fraction”—even if they were fewer in number. Quantity has a quality all its own.

Did the Imperial Era favor martial values?

Perhaps the Empire was less than ideal in maintaining cognitive ability, but surely its rulers believed in warrior values? And surely they helped maintain those values in the population?

Yes and no. The Roman Empire, like almost all states, was created through violence and maintained through violence. This point was made by Augustine in the fifth century:

… what are kingdoms except great robber bands? For what are robber bands except little kingdoms? The band also is a group of men governed by the orders of a leader, bound by a social compact, and its booty is divided according to a law agreed upon. If by repeatedly adding desperate men this plague grows to the point where it holds territory and establishes a fixed seat, seizes cities and subdues peoples, then it more conspicuously assumes the name of kingdom … [Augustine. De civitate dei 4.4]

Though created through violence, the Roman State outlawed its use for everyone but itself. That monopoly was challenged whenever individuals acted violently to achieve their own ends. Such people, called bandits (latrones), made themselves adversaries of the State and, when caught, were punished by being thrown to the beasts, burned alive, or crucified (Frost, 2010).

The result was a social contradiction. Whereas the State could achieve its ends violently, the people had to achieve theirs peacefully. What was legitimate for one was illegitimate for the other.

The Pax Romana certainly benefited Roman society over the short term. By removing aggressive males from the population, it made life more livable and spurred economic activity, especially long-distance trade. Over the long term, however, social pacification led to genetic pacification. The desire to use violence, even to protect oneself and one’s kin, was steadily removed from the gene pool and replaced with a more docile and submissive mindset (Frost, 2010).

Keep in mind that male aggressiveness is moderately to strongly heritable. A heritability of 40% has been estimated through a meta-analysis of 51 twin and adoption studies (Rhee and Waldman, 2002). A later twin study indicates a heritability of 96%, the subjects being 9–10 year-olds from diverse ethnic backgrounds (Baker et al., 2007). This higher estimate reflects the closer ages of the subjects and the use of a panel of evaluators to rate each of them. According to another twin study, heritability is 40% when the twins have different evaluators and 69% when they have the same evaluator (Barker et al., 2009). Finally, a recent review paper has concluded that about half the variance in aggressive behavior is genetic in origin (Veroude et al., 2015)

The Pax Romana thus pacified the Roman population not only socially but also genetically. One notable outcome was that people became less willing to enlist than those of earlier generations, and many would pay gold or cut off their thumbs to evade military service (Swain and Edwards, 2004, pp. 156-157; Williams and Friell, 1994, p. 37). From the fourth century onward, the army was suffering from a lack of recruits and a growing dependence on foreign mercenaries (Southern and Dixon, 1996, pp. 67-72). A new kind of Roman was emerging, one less interested in violence and more submissive to authority. In fact, the new Roman was coming to see aggressive conduct as wrong, even wicked.

This was both a cause and an effect of the spread of Christianity. The latter proved to be a better fit for the new Roman.

Lessons for us today

Can we learn from Rome’s example? Yes, but the lessons are mostly negative. The Empire owed its existence to qualities of mind and behavior that existed previously—during the time of the Republic and earlier. That mental and behavioral capital was run down during the Imperial Era.

Some intellectuals and even a few emperors understood what was happening, but little could be done without abandoning Imperial ambitions and returning to the sober existence of former times. Successful individuals were now pursuing the acquisition of material wealth, even to the detriment of family life. As for sexual desire, it could be satisfied in less cumbersome ways, with slaves or prostitutes. A new sexual norm had become established, and few would challenge it.

Some emperors did, but they ran into resistance from the very people whose lineages were dying out (Sullivan, 2009). In 27 BCE, Augustus Caesar condemned childlessness in a speech to Rome’s equestrian class:

For you are committing murder in not begetting in the first place those who ought to be your descendants; you are committing sacrilege in putting an end to the names and honours of your ancestors; and you are guilty of impiety in that you are abolishing your families, which were instituted by the gods, and destroying the greatest of offerings to them — human life. [Cassius Dio. Roman History, 56.5.2]

Nor could Rome’s leaders do much about other long-term problems, like the declining quality of conscripts. The only workable solution was to hire more foreign mercenaries, who could see close-up how weak the Romans really were.

Another long-term problem was dependence on slavery. Slaves had become essential to the economy, particularly agriculture. That dependence proved to be an Achilles’ heel: agricultural slaves generally had high time preference and, if left on their own, would produce only enough for their own needs, plus a small surplus (Harper, 2011, pp. 176, 250-254). They thus had to be coerced to produce enough for the entire market. Whenever that coercion weakened, during times of unrest or invasion, production fell sharply. The Romans knew this. Everyone knew this.

But the benefits of slavery were too seductive. It wasn’t just the monetary benefits. Slave-owners loved the access to young nubile women, without marital obligations. Slaves knew this weakness, as exemplified by a character from a fifth-century comedy: “We all steal and no one turns traitor, for we are all in it together. We watch out for the master and divert him, for slaves and slave-girls are in alliance” (Harper, 2011, p. 251).

There thus arose a population of alumni—children of masters and slave girls or simply emancipated boys and girls for whom the master had developed affection. If a master had no children by his wife, he could leave his property to his alumni (Rawson, 1986, 2014, pp. 173-179). Thus, upper-class men weren’t simply having fewer children by their wives; they were also having more by slave girls. As a result, they were no longer passing on the mental and behavioral characteristics of their social class to future generations.

Banquet scene, fresco from Pompeii (Casa dei Casti Amanti)

Rome could be saved only by a moral revolution. When Constantine the Great legalized Christianity, he saw it as a means to revitalize and preserve the Empire. Was he himself a Christian? Doubtful. His edicts were more consistent with a pagan mindset:

314 CE. Apprehended slaves trying to run back to barbarian lands should either have their feet cut off or be sent into the mine.

315 CE. Slaves and freedmen guilty of kidnapping are thrown to the animals and freeborn guilty of kidnapping are condemned to the gladiatorial games with no possibility for resistance.

326 CE. Because of their lowly status, barmaids are outside of adultery laws.

326 CE. Women who become involved with or marry slaves are to be executed and the slaves burned.

332 CE. [Edict for] setting torture as the proper way to ascertain truth from slaves. (Thompson, 2008)

Christianity failed to save the Empire and may even have hastened the eventual collapse. It did, however, lay the basis for a new civilization that would not only reverse the demographic decline of the Imperial Era but also restart cognitive evolution. It did so in two ways:

by favoring monogamy and, conversely, by limiting male polygyny and female hypergamy; and

by favoring the peace, order, and stability that allowed entrepreneurial individuals to exploit a growing range of new cognitive tasks, thereby ensuring their success both economically and demographically.

Thus arose the new civilization of Christian Europe, and that rise began long before the conquest of the Americas, the invention of printing, the Atlantic slave trade, and the Protestant Reformation. The root cause was a new societal model of social and biological reproduction (Frost, 2022).

References

Augustine (1963). The City of God against the Pagans, (W.H. Green, Trans.). Loeb Classical Library, London: William Heinemann. https://www.loebclassics.com/view/augustine-city_god_pagans/1957/pb_LCL411.1.xml

Baker L.A., K.C. Jacobson, A. Raine, D.I. Lozano, and S. Bezdjian. (2007). Genetic and environmental bases of childhood antisocial behavior: a multi-informant twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 116: 219–235. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.219

Barker E.D., H. Larson, E. Viding, B. Maughan, F. Rijsdijk, N. Fontaine, and R. Plomin. (2009). Common genetic but specific environmental influences for aggressive and deceitful behaviors in preadolescent males. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 31: 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9132-6

Caldwell, J.C. (2004). Fertility control in the classical world: Was there an ancient fertility transition? Journal of Population Research 21:1. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03032208

Cassius Dio (1924) Roman History. Loeb Classical Library. Boston: Harvard University Press. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/56*.html

Clark, G. (2007). A Farewell to Alms. A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Clark, G. (2009). The domestication of man: the social implications of Darwin. ArtefaCToS 2: 64-80. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277275046_The_Domestication_of_Man_The_Social_Implications_of_Darwin

Clark, G. (2023). The inheritance of social status: England, 1600 to 2022. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120(27): e2300926120 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300926120

Frier, B. W. (2001). More is worse: some observations on the population of the Roman Empire. In: Debating Roman Demography (pp. 139-159). Brill.

Frost, P. (2010). The Roman State and genetic pacification. Evolutionary Psychology 8(3): 376-389. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F147470491000800306

Frost, P. (2022). When did Europe pull ahead? And why? Peter Frost’s Newsletter, November 21. https://peterfrost.substack.com/p/when-did-europe-pull-ahead-and-why

Harper, K. (2011). Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275-425. Cambridge University Press.

Harris, W. (1999). Demography, Geography and the Sources of Roman Slaves. Journal of Roman Studies 89: 62-75. https://doi.org/10.2307/300734

Hopkins, K. (1965). Contraception in the Roman Empire. Comparative Studies in Society and History 8(1): 124-151. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500003935

Jongman, W. M., J.P. Jacobs, and G.M.K. Goldewijk. (2019). Health and wealth in the Roman Empire. Economics & Human Biology 34: 138-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.01.005

Lee, J. J., R. Wedow, A. Okbay, E. Kong, O. Maghzian, M. Zacher, et al. (2018). Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nature Genetics 50(8): 1112-1121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3

Perry, M.J. (2013). Gender, Manumission, and the Roman Freedwoman. Cambridge University Press.

Piffer, D. (2019). Evidence for Recent Polygenic Selection on Educational Attainment and Intelligence Inferred from Gwas Hits: A Replication of Previous Findings Using Recent Data. Psych 1: 55-75. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych1010005

Piffer D, E. Dutton, and E.O.W. Kirkegaard. (2023). Intelligence Trends in Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of Roman Polygenic Scores. OpenPsych. Published online July 21, 2023. https://doi.org/10.26775/OP.2023.07.21

Rawson, B. (1986). Children in the Roman familia. In: B. Rawson (ed.) The family in ancient Rome: new perspectives, (pp. 170-200). Ithaca (New York): Cornell University Press.

Rhee S.H., and I.D. Waldman. (2002). Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin 128: 490–529. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.490

Roetzel, C.J. (2000). Sex and the single god: celibacy as social deviancy in the Roman period. In: S.G. Wilson and M. Desjardins (eds). Text and Artefact in the Religions of Mediterranean Antiquity. Essays in Honour of Peter Richardson (pp. 231-248), Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Saller, R. (2014). Slavery and the Roman family. In: Classical Slavery (pp. 82-110). Routledge.

Southern, P., and K.R. Dixon. (1996). The Late Roman Army. Yale University Press.

Sullivan, V. (2009). Increasing Fertility in the Roman Late Republic and Early Empire. MA thesis, History, North Carolina State University. https://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/handle/1840.16/812

Swain, S., and M.J. Edwards. (2004). Approaching Late Antiquity: The Transformation from Early to Late Empire. New York: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, G.L. (2008). Works of Constantine I (the Great). Fourth-Century Christianity. Wisconsin Lutheran College. https://www.fourthcentury.com/works-of-constantine/

Veroude, K., Y. Zhang-James, N. Fernàndez-Castillo, M.J. Bakker, B. Cormand, and S.V. Faraone. (2016). Genetics of aggressive behavior: an overview. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 171(1): 3-43. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.32364

Williams, S., and Friell, G. (1994). Friends, Romans or countrymen? Barbarians in the empire. History Today 44: 34-40.

Woodley of Menie, M.A., S. Younuskunju, B. Balan, and D. Piffer. (2017). . Twin Research and Human Genetics 20: 271-280. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2017.37

Woodley of Menie, M.A., J. Delhez, M. Peñaherrera-Aguirre, and E.O.W. Kirkegaard. (2019). Cognitive archeogenetics of ancient and modern Greeks. London Conference on Intelligence. https://www.altcensored.com/watch?v=UES_tpDxz9A

You are missing by far the most important reason.

Imperial Romans were nothing like Republican Romans. The Republican Romans were demographically replaced almost in their entirety.

While the Italic Republican Romans were genetically similar to Southern French or Northern Spaniards, the Imperial Romans contained significant Middle Eastern ancestry (Levantine and Anatolian, in addition to Greek) and were closest to Greek Islanders and Cypriots.

When Alexander conquered the Middle East it turned many parts of that world culturally Greek. The Hellenized groups, especially from Anatolia and the Levant, moved to Greece so that in a short amount of time Hellenistic Greece became overwhelmingly Middle Eastern in ancestry.

These groups moved into Italy and in fact there are historical attestations regarding this. Of course they didn't do DNA tests for ancestry back then, they just considered them all to be Greeks.

So, Christianity made people weak as well as Roman state did through genetic pacification? I wouldn't say medeival age Europeans were peaceful