Was Franz Boas a race realist?

A revisionist look

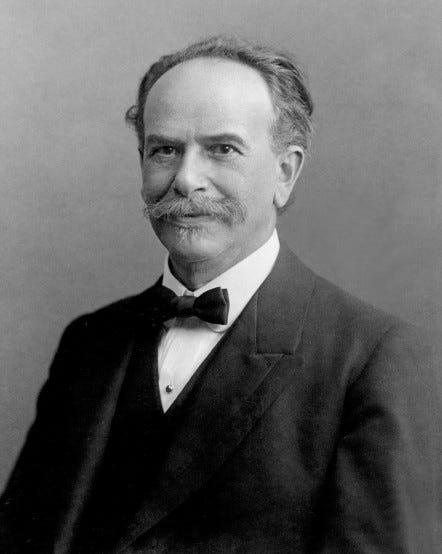

Franz Boas, c. 1915 (Canadian Museum of History)

Hitler’s rise to power had an electrifying effect on Jewish scholars around the world, including Franz Boas. Previously, he had been favorable to the idea that human populations differ in cognitive ability. He now threw himself into the fight against “racism” — a word entering the language as a synonym for Nazism.

The anthropologist Franz Boas (1858-1942) is seen as a key figure in the development of current views on race and racism. Historian Carl Degler and psychologist Kevin MacDonald describe him as leading a “life-long assault on the idea that race was a primary source of the differences to be found in the mental or social capabilities of human groups” (Degler, 1991, p. 61; MacDonald, 1998, p. 23).

This view has become widespread among critics and admirers alike. Yet it is largely false.

In fact, Boas argued repeatedly for the idea that mental capability differs among human groups, a position he abandoned only with the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. After his death in 1942, and the end of the Second World War, his life work would be used to justify the emerging antiracist consensus. He has since become a mythical founder of that consensus, and his real role in history — as a man searching for the truth — has been obscured to the point of misrepresentation.

Boas on race and racial differences

In 1858, Boas was born into a non-observant Jewish family in Germany. He first took an interest in human differences while studying geography, particularly during his fieldwork among the Inuit of Baffin Island (1883-1884). He then worked for three years at the Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin before leaving for an academic position in the United States.

Boas first presented his views on racial differences in an 1894 speech on ‘Human Faculty as Determined by Race.’

It does not seem probable that the minds of races which show variations in their anatomical structure should act in exactly the same manner. Differences of structure must be accompanied by differences of function, physiological as well as psychological; and, as we found clear evidence of difference in structure between the races, so we must anticipate that differences in mental characteristics will be found. Thus, a smaller size or lesser number of nervous elements would probably entail loss of mental energy, and paucity of connections in the central nervous system would produce sluggishness of the mind. (Boas, 1894, p. 25)

He did not limit the race concept to continent-wide groups. For him, a “race” could simply be a clan that ends up diverging genetically from other clans through the reproductive success of its leading families:

Furthermore, as certain anatomical traits are found to be hereditary in certain families and hence in tribes and perhaps even in peoples, in the same manner mental traits characterize certain families and may prevail among tribes. (Boas, 1894, p. 25)

But were such traits passed on genetically or culturally?

It seems, however, an impossible undertaking to separate in a satisfactory manner the social and the hereditary features. Galton's attempt to establish the laws of hereditary genius points out a way of treatment for these questions which will prove useful in so far as it opens a method of determining the influence of heredity upon mental qualities (Boas, 1894, p. 25)

These mental differences are statistical in nature, with significant overlap between racial groups:

We have shown that the anatomical evidence is such, that we may expect to find the races not equally gifted. While we have no right to consider one more ape-like than the other, the differences are such that some have probably greater mental vigor than others. The variations are, however, such that we may expect many individuals of all races to be equally gifted, while the number of men and women of higher ability will differ. (Boas, 1894, p. 28)

The above points would be expanded upon in his 1901 article about ‘The Mind of Primitive Man.’

The thoughts and actions of civilized man and those found in more primitive forms of society prove that, in various groups of mankind, the mind responds quite differently when exposed to the same conditions. Lack of logical connection in its conclusions, lack of control of will, are apparently two of its fundamental characteristics in primitive society. In the formation of opinions, belief takes the place of logical demonstration. The emotional values of opinions is great, and consequently they quickly lead to action. The will appears unbalanced, there being a readiness to yield to strong emotions, and a stubborn resistance in trifling matters. (Boas, 1901, p. 1)

Boas believed that humans differ mentally and emotionally for two possible reasons: 1) their minds are organized differently or 2) their minds are subjected to differences in “habit” and “individual experience.” Between these two explanations, he steered a middle course:

A number of anatomical facts point to the conclusion that the races of Africa, Australia, and Melanesia are to a certain extent inferior to the races of Asia, America, and Europe. We find that on the average the size of the brain of the negroid races is less than the size of the brain of the other races; and the difference in favor of the mongoloid and white races is so great that we are justified in assuming a certain correlation between their mental ability and the increased size of their brain. At the same time it must be borne in mind that the variability of the mongoloid and white races on the one hand, and of the negroid races on the other, is so great that only a small number, comparatively speaking, of individuals belonging to the latter have brains smaller than any brains found among the former; and that, on the other hand, only a few individuals of the mongoloid races have brains so large that they would not occur at all among the black races …

The question whether the power to inhibit impulses is the same in all races of man is not so easily answered. It is an impression obtained by many travellers, and also based upon experiences gained in our own country, that primitive man and the less educated have in common a lack of control of emotions, that they give way more readily to an impulse than civilized man and the highly educated. I believe that this conception is based largely upon the neglect to consider the occasions on which a strong control of impulses is demanded in various forms of society …. [Taboos and food prohibitions] are very numerous, and prove that primitive man has the ability to control his impulses, but that this control is exerted on occasions which depend upon the character of the social life of the people, and which do not coincide with the occasions on which we expect and require control of impulses …

It is not impossible that the degree of development of these functions may differ somewhat among different types of man; but I do not believe that we are able at the present time to form a just valuation of the power of abstraction, of control, and of choice among different races. (Boas, 1901, pp. 3-6)

This article closes with a discussion of cultural relativism, particularly how human groups differ in their notions of right and wrong. Although such differences are now usually seen as culturally determined — each culture conditions its members to think in a certain way — Boas saw the determination as being both cultural (“traditions”) and innate (“equilibrium of emotion and reason”).

It is somewhat difficult for us to recognize that the value which we attribute to our own civilization is due to the fact that we participate in this civilization, and that it has been controlling all our actions since the time of our birth; but it is certainly conceivable that there may be other civilizations, based perhaps on different traditions and on a different equilibrium of emotion and reason, which are of no less value than ours … (Boas, 1901, p. 11)

This article was the basis for a book of the same title, first published in 1911. Many more people are familiar with the 1921 and 1938 editions, which downplay or eliminate the racialist statements of the first edition.

In 1905, Boas wrote an article on ‘The Negro and the Demands of Modern Life’ for a special issue of Charities, a magazine aimed at a “familiar cast of Christian reformers, social workers, and social scientists” (Baker, 2022). Even to that audience, he affirmed that the average negro brain is "smaller than that of other races" and that it was "plausible that certain differences of form of brain exist." He then qualified this statement by adding: “We must remember that individually the correlation ... is often overshadowed by other causes, and that we find a considerable number of great men with slight brain weight.” He nonetheless concluded: “We may, therefore, expect less average ability and also, on account of probable anatomical differences, somewhat different mental tendencies” (Williams, 1996, p. 17).

That same year, he discussed "the desirability of collecting more definite information in relation to certain traits of the Negro race that seem of fundamental importance in determining the policy to be pursued towards that race" (Williams, 1996, p. 18). In particular, he had two questions in mind:

(1) Is there an earlier arrest of mental and physical development in the Negro child, as compared with the white child? And, if so, is this arrest due to social causes or to anatomical and physiological conditions?

(2) What is the position of the mulatto child and of the adult mulatto in relation to the two races? Is he an intermediate type, or is there a tendency of reversion towards either race? So that particularly gifted mulattoes have to be considered as reversals of the white race. The question of the physical vigor of the mulatto could be taken up at the same time. (Williams, 1996, p. 19)

In a private letter, he spoke more openly:

You may be aware that in my opinion the assumption seems justifiable that on the average the mental capacity of the negro may be a little less than that of the white, but that the capacities of the bulk of both races are on the same level. (Williams, 1996, p. 19)

These views were later reiterated in his 1909 article on ‘Race Problems in America.’

I do not believe that the negro is, in his physical and mental make-up, the same as the European. The anatomical differences are so great that corresponding mental differences are plausible. There may exist differences in character and in the direction of specific aptitudes. There is, however, no proof whatever that these differences signify any appreciable degree of inferiority of the negro, notwithstanding the slightly inferior size, and perhaps lesser complexity of structure, of his brain; for these racial differences are much less than the range of variation found in either race considered by itself. (Boas, 1909, pp. 847-848)

Boas and anti-racism

Were the above statements anti-racist for their time? Not really. Many contemporaries of Boas held strong views on human equality, including some in his entourage. In Berlin, he had done post-graduate work under the anthropologist Rudolf Virchow, who rejected Darwinian evolution and attributed human differences to the direct action of the environment. Boas had also studied under the ethnologist Adolf Bastian, who argued for the “psychic unity of mankind,” i.e., that all humans have the same intellectual capacity, and all cultures are based on the same basic mental principles (Wikipedia, 2025). In the United States, Boas would work with academics who supported the goal of making African Americans free and equal citizens. Although Reconstruction had been mostly abandoned by the turn of the century, a large segment of Northern opinion remained sympathetic to its aims and hotly contested the disenfranchisement of Black Southerners.

Thus, during his long tenure at Columbia University (1896-1942), Boas often expressed his views to people who rejected the possibility of innate mental differences. In such situations, he tailored his message to his audience, like the African Americans who attended his 1906 commencement address at Atlanta University:

The physical inferiority of the Negro race, if it exists at all, is insignificant when compared to the wide range of individual variability in each race. There is no anatomical evidence available that would sustain the view that the bulk of the Negro race could not become as useful citizens as the members of any other race. That there may be slightly different hereditary traits seems plausible, but it is entirely arbitrary to assume that those of the Negro, because perhaps slightly different, must be of an inferior type. (Boas, 1906)

This address was made at the invitation of W.E.B. Du Bois, who had read the contribution by Boas to the special issue of Charities, having himself contributed to the same issue. It was the start of a relationship that would open many doors for the aspiring anthropologist, notably an invitation to publish in The Crisis, the newly created magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (Baker, 2022). Its editor, W.E.B. Du Bois, asked him to write a feature article for the second issue. Even to that audience, and despite reassuring words to the contrary, Boas still argued for the existence of differences in “mental characteristics” between African and European Americans:

The existing differences are differences in kind, not in value. This implies that the biological evidence also does not sustain the view, which is so often proposed, that the mental power of the one race is higher than that of the other, although their mental qualities show, presumably, differences analogous to the existing anatomical and physiological differences …

Thus it may safely be said that there is no anthropological evidence showing inferiority of the Negro race as compared with the white race, although we may assume that differences in mental characteristics of the two races exist. (Boas, 1910)

Five years later, the same doublespeak appeared in his preface to a book by Mary White Ovington, an NAACP cofounder:

Many students of anthropology recognize that no proof can be given of any material inferiority of the Negro race; that without doubt the bulk of the individuals composing the race are equal in mental aptitude to the bulk of our own people; that, although their hereditary aptitudes may lie in slightly different directions, it is very improbable that the majority of individuals composing the white race should possess greater ability than the Negro race. (Ovington, 1915, p. vii)

These new publishing opportunities may explain certain changes in wording between the 1911 and 1921 editions of The Mind of Primitive Man. Although Boas became more careful in expressing himself on the subject, his actual views show few signs of change. As late as 1928, he was still arguing for the existence of racial differences in mental capability, as seen in his work Anthropology and Modern Life:

Nevertheless the distribution of individuals and of family lines in the various races differs. When we select among the Europeans a group with large brains, their frequency will be relatively high, while among the Negroes the frequency of occurrence of the corresponding group will be low. If, for instance, there are 50 per cent of a European population who have a brain weight of more than, let us say, 1,500 grams, there may be only 20 per cent of Negroes of the same class. Therefore 30 per cent of the large-brained Europeans cannot be matched by any corresponding group of Negroes. (Boas, 1962[1928], p. 38)

To be sure, he also emphasized the existence of overlap between the two populations, but this caveat had the effect of driving home his initial point:

The brain in each race is very variable in size and the "overlapping" of individuals in the races is marked. It is not possible to identify an individual as a Negro or White according to the size and form of the brain, but serially the Negro brain is less extremely human than that of the White. (Boas, 19621928], pp. 39-40)

The differences between races are so small that they lie within the narrow range in the limits of which all forms may function equally well. We cannot say that the ratio of inadequate brains and nervous systems, that function noticeably worse than the norm, is the same in every race, nor that those of rare excellence are equally frequent. It is not improbable that such differences may exist in the same way as we find different ranges of adjustability in other organs. (Boas, 1962[1928], p. 41)

This was a recurring pattern in his line of argument. He would first assert the existence of a racial difference in mental capability, then qualify his assertion by pointing to the existence of overlap and, finally, qualify his qualification by noting that a small statistical difference can produce large differences among the very smart and the very dull.

Boas may have had plans during the mid-1920s for a comparative IQ study of African Americans and Euro Americans. In 1924, one of his PhD students, a young Margaret Mead, prepared an article on different methodologies for testing racial differences in IQ. It was written before her Samoan fieldwork and is the sort of research assistance that she, as a PhD novice, would have provided her supervisor before beginning her own research.

The article has a neutral tone. Although Mead argued that racial differences in IQ may be illusory (i.e., due to differences in education or language familiarity), she did not rule out their existence. In particular, she pointed to admixture studies as the best means to distinguish between true racial differences and false ones: “If the genealogical method could be subjected to extensive verification and supplemented by some technique for holding the other factors constant it might be productive of valuable results” (Mead, 1926, p. 661). By no means a blank-slatist, she deplored “the present state of ignorance concerning the laws regulating the inheritance of mental traits” (Mead, 1926, p. 667).

The final decade (1932-1942)

The first three decades of the 20th century had seen a slow shift toward the idea that all human races possess the same mental capabilities. In the early 1930s, this shift suddenly accelerated in response to events in the very land where Boas had been born. Alarmed, he and others threw themselves into the fight against “racism” — a word coming into use as a synonym for Nazism and other “blood and soil” ideologies (Frost, 2015). To that end, he purged any remaining racialist statements from the 1938 edition of The Mind of Primitive Man, perhaps in the belief that the anti-Nazi struggle required a united front against all forms of racial discrimination.

This chapter of his life, which ended with his death in 1942, is summarized in one of his obituaries:

Dr. Boas, who had studied and written widely in all fields of anthropology devoted most of his researches during the past few years to the study of the "race question," especially so after the rise of the Nazis in Germany. Discussing his efforts to disprove what he called "this Nordic nonsense," Prof. Boas said upon his retirement from teaching in 1936 that "with the present condition of the world, I consider the race question a most important one. I will try to clean up some of the nonsense that is being spread about race those days. I think the question is particularly important for this country, too; as here also people are going crazy." (JTA, 1942)

After his death, the mantle of Boasian anthropology fell to his two leading students: Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead. Neither they nor many other academics wished to end the war on racism when the Second World War ended. This stance had at least three justifications:

Many felt that nationalism had caused the war and that any discourse on human differences, no matter how scholarly, would make nationalism more intractable. A lasting peace could be built only on internationalism.

Antisemitism was far from dead in 1945. There were fears of a resurgence, and such a resurgence could not be fought alone. As during the war, this fight would require a united front against any belief in human differences.

The postwar era would be dominated by a Cold War rivalry for the hearts and minds of emerging nations in Africa, Asia and elsewhere. Discriminatory practices at home, notably in education and immigration, became a source of embarrassment to the U.S. in its foreign relations.

Boas had sought to strike a balance between nature and nurture in the study of human populations. Events intervened, however, and Boasian anthropology was conscripted to fight the war against racism. Eight decades later, that war is still being fought.

References

Baker, L.D. (2022). W.E.B. Du Bois and American anthropology. In: The Oxford Handbook of W.E.B. Du Bois, edited by A.D. Morris, M. Schwarrz, C. Johnson-Odim, W. Allen, M.A. Hunter, et al. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190062767.001.0001

Boas, F. (1894). Human faculty as determined by race. Address by Franz Boas before the Section of Anthropology, American Association for the Advancement of Science, at the Brooklyn meeting. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/37/Human_faculty_as_determined_by_race_-_address_%28IA_101313603.nlm.nih.gov%29.pdf

Boas, F. (1901). The mind of primitive man. The Journal of American Folk-Lore, 14, (52), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.13.321.281

Boas, F. (1904). The Negro and the Demands of Modern Life: Ethnic and Anatomical Considerations. Charities, 15(1), 85-88.

Boas, F. (1906). Commencement address at Atlanta University, May 31. Atlanta University Leaflet, No. 19. http://www.webdubois.org/BoasAtlantaCommencement.html

Boas, F. (1909). Race problems in America. Science, 29(752), 839-849. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.29.752.839

Boas, F. (1910). The real race problem. The Crisis, 1(2), 22-25. https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr507810/

Boas, F. (1911). The Mind of Primitive Man. 1st edition, New York: Macmillan

Boas, F. (1921). The Mind of Primitive Man. 2nd edition, New York: Macmillan.

Boas, F. (1962[1928]). Anthropology and Modern Life. New York: Norton & Co.

Boas, F. (1938). The Mind of Primitive Man. 3rd edition, New York: Macmillan.

Boas, F. (1974). A Franz Boas Reader. The Shaping of American Anthropology, 1883-1911. G.W. Stocking Jr. (ed.), Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Degler, C. (1991). In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frost, P. (2015). Birth of a word. Evo and Proud, May 23. https://evoandproud.blogspot.com/2015/05/birth-of-word.html

JTA (1942). Dr. Franz Boas, Debunker of Nazi Racial Theories, Dies in New York, December 23. http://www.jta.org/1942/12/23/archive/dr-franz-boas-debunker-of-nazi-racial-theories-dies-in-new-york

MacDonald, K. (1998). The Culture of Critique. An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements. Praeger Publishers.

Mead, M. (1926). The methodology of racial testing: its significance for sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 31(5), 577-720. https://doi.org/10.1086/213952

Ovington, M.W. (1911). Half a Man. The Status of the Negro in New York. Foreword by Dr. Franz Boas of Columbia University. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Wikipedia (2025). Franz Boas. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Boas

Williams Jr., V.J. (1996). Rethinking Race: Franz Boas and His Contemporaries. University Press of Kentucky. https://books.google.ca/books?id=MKnIOfHNxXMC&printsec=frontcover&hl=fr#v=onepage&q&f=true

He allowed his personal ethnic interests to compromise his objectivity. He betrayed science.

Thanks for the interesting deep dive into Boas's evolution of wokeness.

A title might be The Blue Pilling of Boas.

"Was Franz Boas a race realist?"

The answer to the question is found in the qualifier 'was'.