The archaeology of the mind

How ancient DNA is shedding new light on prehistory and history

Impressions of a cityscape, Louis-George Legrand (1801-1883)

We adapt not only to natural habitats but also to culture. As the latter became more important, human evolution speeded up to cope with new demands on cognitive ability.

Genetic evolution accelerated some 10,000 years ago in our species. Back then, humans already occupied the full range of natural environments from the tropics to the arctic. They were now adapting to new cultural environments. First, there was farming and life in villages, towns, and cities. Then came other changes: specialization of labor, formation of states, development of reading and writing, codification of social norms into law, and so on.

We used to think that cultural evolution simply replaced genetic evolution. In reality, the two have pushed each other forward, even into the time of recorded history. Humans create culture, and culture recreates humans — by selecting those who better fit in and cope with its demands on body and mind.

The mind, in particular, has been shaped by this coevolution with culture. To varying degrees, this has meant:

processing an increasing volume of written texts and numerical data

keeping track of interactions with more people, most of whom are not close kin or even friends

imagining how to make tools for an ever-wider range of tasks

creating mental models with a longer timeline. Simply put, we no longer live mainly in the present. To act in the present, we must move back and forth between an imagined past and multiple imagined futures, thereby increasing the two-way interaction between thought and action.

This new view of recent human evolution is backed by several recent studies. At first, researchers had to use indirect methods to estimate when and how fast the human genome changed during prehistory and history. By measuring the degree of decay in linkage disequilibrium at a gene, they could estimate the length of time since a mutation or a selective sweep.

This method has been used in two studies of recent human evolution.

Hawks et al. (2007) - humans over the past 40,000 years

Almost 4 million SNPs were analyzed to estimate the rate of change to the human genome over the past 40,000 years.

Findings:

Genetic evolution accelerated more than a hundredfold some 10,000 years ago, when hunting and gathering gave way to farming and other cultural changes (sedentary living, growth of towns and cities, rise of social complexity, etc.).

This period of rapid evolution lasted well into the time of recorded history, peaking 8,000 years ago in Africa and 5,250 years ago in Europe.

In actual fact, these peaks were even more recent. “[T]he peak ages of new selected variants in our data do not reflect the highest intensity of selection, but merely our ability to detect selection. Because of the recent acceleration, many more new adaptive mutations should exist than have yet been ascertained, occurring at a faster and faster rate during historic times.”

This rapid evolution involved physiological adaptations to new diets or new diseases and, above all, cognitive adaptations to new ways of doing things. “[T]he rapid cultural evolution during the Late Pleistocene created vastly more opportunities for further genetic change, not fewer, as new avenues emerged for communication, social interactions, and creativity” (Hawks et al., 2007).

Libedinsky (2025) - mostly ancestors of Europeans over the past 5 million years

Over 13 million SNPs were analyzed to estimate the rate of change to the human genome over the past 5 million years.

Findings:

Human evolution was rapid during two periods: 1) 2.4 million to 280,000 years ago with a peak around 1.1 million years ago; and 2) 280,000 to 1,700 years ago with a peak around 55,000 years ago.

The second period saw rapid evolution in three domains: 1) vision; 2) mental function; and 3) nutrient absorption, digestion, and storage. There was much less evolutionary change in metabolism, skeletal development, and the immune system.

Changes to the neocortex were more recent than changes elsewhere in the brain (Libedinsky, 2025).

Like Hawks, Libedinsky identified a period of rapid evolution that went well past the spread of humans out of Africa, perhaps even into historic times. But his analysis shows it beginning earlier and peaking earlier, perhaps because of differences between his dataset and Hawks’. The latter dataset, though smaller, was divided equally among several human groups: two of European descent; three of East Asian descent; one of mixed European/Amerindian descent; one of South Asian descent; and four of African descent. Because Libedinsky mostly used data from people of European descent, he largely excluded the evolutionary changes that non-Europeans have experienced over the past 50,000 years since the Out-of-Africa event (Hawks, 2023).

A new research tool

With the retrieval of DNA from human remains, the past few years have seen a revolution in studies of recent human evolution. We can now directly see how human populations have evolved over time, not only physically but also mentally and behaviorally.

Kuijpers et al. (2022) - Europeans over the past ~35,000 years

This was an analysis of genomes from 827 Europeans who lived in the Upper Paleolithic (>11,000 years ago), the Mesolithic (11,000-5,500 years ago), the Neolithic (8,500-3,900 years ago), and the post-Neolithic (5,000 to “more recent ages”). Analysis also included genomes from 250 individuals who now live in present-day Europe.

Evolution of cognitive ability was measured by alleles associated with intelligence, fluid intelligence, and educational attainment (EA).

Findings:

No change in mean cognitive ability during the long period of hunting and gathering

With the emergence of farming, a steady rise throughout the Neolithic and into historic times

Stagnation during the classical era of civilization

A steady rise over the last few centuries (Kuijpers et al., 2022; see also Frost, 2024a).

Piffer et al. (2023) - Central Italians over the past 10,000 years

This was an analysis of genomes from 127 individuals who lived in central Italy during the pre-Iron Age (10,000-900 BCE), the Iron Age and the Republican Era (900-27 BCE), the Imperial Era (27 BCE-300 CE), Late Antiquity (300-700), and medieval/early modern times (700-1800). Analysis also included genomes from 33 individuals who now live in central Italy. Cognitive ability was measured by alleles associated with educational attainment (EA4)

Findings:

A steady rise in mean cognitive ability through prehistory and into the time of the Roman Republic

A sharp fall during the Imperial Era.

A steady rise from Late Antiquity to early modern times (Frost, 2024b)

A fall beginning somewhere after 1800 and continuing to the present (Piffer et al., 2023).

Rise, fall, and renewed rise of mean cognitive ability in central Italy (Piffer et al, 2023, Figure 1)

Piffer & Kirkegaard (2024) - Europeans over the past ~35,000 years

This was a replication of Kuijpers et al. (2022), using genomes from more individuals and using more alleles to calculate polygenic scores. The genomes came from 2,625 individuals who lived in Europe from 32,600 to 246 years ago. Cognitive ability was measured by alleles associated with occupational status, EA, and IQ. The alleles associated with EA were identified by other research teams from two large samples, one with over a million participants (EA3) and the other with three million (EA4).

Findings:

No change in mean cognitive ability from 35,000 to 15,000 years ago.

A rise beginning near the end of the last ice age and continuing to the present (Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024; see also Frost, 2024a)

In this study, the upward trend is more continuous and thus less steep, perhaps because of samples from non-Romanized regions that suffered less from the cognitive decline of the Imperial Era.

As with the last study, we see a close alignment of all three measures of cognitive ability. The evolutionary change has clearly been in this trait, and not in some non-cognitive aspect of educational attainment.

Akbari et al. (2024) - Europeans over the past 9,000 years

This was a replication of Kuijpers et al. (2022) and Piffer and Kirkegaard (2024), using genomes from even more individuals: 8,433 Europeans from the past 14,000 years and 6,510 from present-day Europe. Cognitive ability was measured by alleles associated with IQ, household income, and EA (based on alleles identified from a sample of about a million Europeans and East Asians, see Chen et al., 2024).

Findings:

A steep rise in mean cognitive ability from 9,000 to 7,000 years ago

A moderate rise from 7,000 to 2,000 years ago

A fall from 2,000 to 1,000 years ago

A rise over the last 1,000 years.

The research team also found strong directional selection acting on many hundreds of alleles over the past 10,000 years. There was selection for lighter skin, for lower risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disease, for slower decline in health with age, and for higher cognitive ability.

Strangely, the paper makes no mention of previous work by John Hawks, Ilan Libedinsky, Yunus Kuijpers, Davide Piffer, and Emil Kirkegaard. The Reich Lab researchers are presented as the first proponents of the new view of recent human evolution.

Previous work has shown that classic selective sweeps driving alleles to fixation have been rare over the broad span of human evolution. Thus, we were surprised that over the last 14,000 years in West Eurasia there have been many hundreds of instances of directional selection with coefficients on the order of 0.5% or more. (Akbari et al., 2024, pp. 9-10)

All three measures show that mean cognitive ability has risen substantially in Europeans over the past 9,000 years (Akbari et al., 2024)

Piffer (2025a) - East Asians over the past 12,000 years

This was a study of genomes from 1,245 individuals who have lived in eastern Eurasia over the past 12,000 years. For earlier periods, not enough samples were available to draw firm conclusions. Cognitive ability was measured by alleles associated with EA or IQ (based on 176,400 East Asians, Chen et al., 2024).

Findings:

No change in mean cognitive ability during the long period of hunting and gathering.

A steady rise beginning 9,000 to 8,000 years ago, apparently with the advent of farming.

Stagnation or decline over the past 1,500 years, possibly due to lower fertility among elite individuals. Stagnation is indicated by alleles associated with EA, and a real decline by alleles associated with IQ (Piffer, 2025a; see also Frost, 2025a).

Why do we see decline with IQ alleles and no change with EA alleles? Perhaps the divergence between the two measures reflects the growing importance of the Imperial Examination (Frost, 2011; Wen et al., 2024). This examination provided access to all levels of China’s civil service. As such, it rewarded not only high cognitive ability but also rule following, submissiveness, and resistance to boredom — in short, the ability to sit still at a desk and do tedious assignments. The latter ability is likely better measured by alleles associated with educational attainment than by those associated with IQ.

Mean cognitive ability in East Asia over the past 12,000 years, as measured by alleles associated with EA (Piffer, 2025a, Figure 3, p. 6)

Mean cognitive ability in East Asia over the past 12,000 years, as measured by alleles associated with IQ (Piffer, 2025a, Figure 6, p. 8)

Piffer & Connor (2025a) - An English region from the 11th to 19th centuries

This was a study of genomes from 269 individuals who lived in one region of England (Cambridge and surrounding area) from the 11th to 19th centuries. Cognitive ability was measured by alleles associated with EA.

Findings:

No clear change until the 1300s, followed by a steady rise in mean cognitive ability until the 19th century.

On a per capita basis, the highly intelligent became ten times more numerous in England between 1000 and 1850, i.e., the top 1% in 1850 were as smart as the top 0.1% in the year 1000 (Piffer & Connor, 2025a; see also Frost, 2025b).

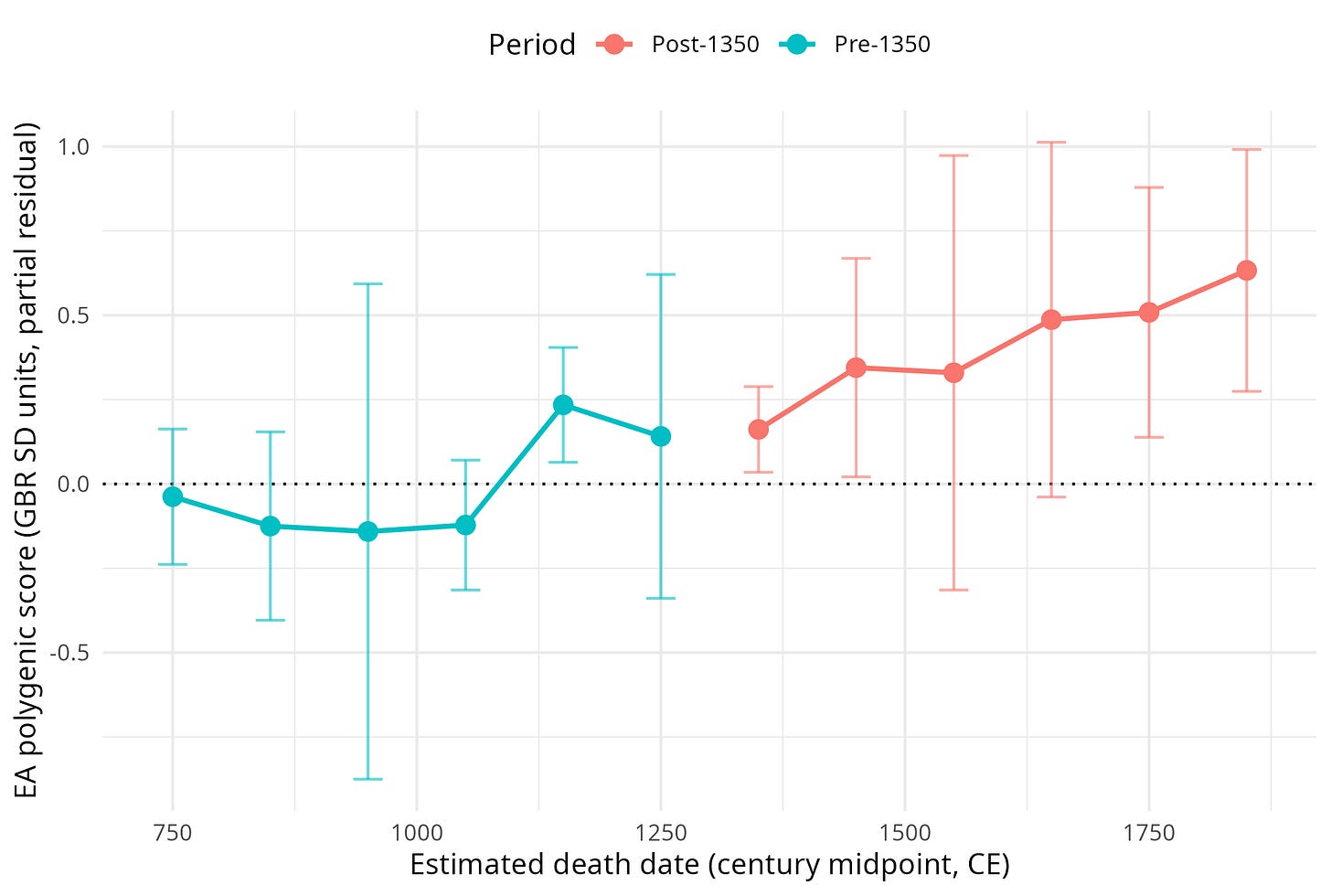

Piffer & Connor (2025b) - Northwest Europeans from the 8th to 19th centuries

This was a replication of the above study with more genomes (n=600) and a broader spatial and temporal scope (Belgium, Denmark, England, Germany, and the Netherlands from the 8th to 19th centuries). Cognitive ability was measured by alleles associated with EA.

Findings:

No clear change until the mid-1300s followed by a steady rise in mean cognitive ability until 1850. The total rise was a little over three quarters of a standard deviation.

The Black Death (1346-1353) may have kickstarted cognitive evolution in northwest Europe by weakening feudalism and freeing up human capital for the emerging market economy: “labour became scarcer, wages rose, and land and capital became relatively cheaper. In that new environment, individuals who could exploit opportunities in trade, crafts, and skilled work had strong advantages” (Piffer, 2025b).

On a per capita basis, the highly intelligent became over ten times more numerous in northwest Europe between 700 and 1850, i.e., the top 1% in 1850 were smarter than the top 0.1% in the year 700 (Piffer & Connor, 2025b; Piffer, 2025b).

Cognitive evolution in northwest Europe from medieval to modern times (Piffer, 2025b)

Has David Reich walked back his finding?

Of the studies presented above, one has especially gained public attention: the 2024 paper by Ali Akbari and other researchers at the David Reich Lab — a renowned research laboratory in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School. David Reich himself has become widely known for his book Who We Are and How We Got Here.

Reich’s team found that mean cognitive ability has risen substantially over the past 9,000 years. The signals of selection are well above the threshold of significance:

We finally observe signals of selection for combinations of alleles that today predict three correlated behavioral traits: scores on intelligence tests (increasing 0.79 ± 0.14), household income (increasing 1.11 ± 0.14), and years of schooling (increasing 0.61 ± 0.13). These signals are all highly polygenic, and we have to drop 463 to 1109 loci for the signals to become nonsignificant (Akbari et al., 2024, p. 9)

This finding was judged important enough to appear in the Abstract:

We also identify selection for combinations of alleles that are today associated with lighter skin color, lower risk for schizophrenia and bipolar disease, slower health decline, and increased measures related to cognitive performance (scores on intelligence tests, household income, and years of schooling). (Akbari et al., 2024)

Yet David Reich seems to deny this finding in a podcast interview with Dwarkesh Patel:

If you look at traits that we know today affect immune disease or metabolic disease, these traits are highly overrepresented by a factor of maybe four in the collection of variants that are changing rapidly over time. Whereas if you look at traits that are affecting cognition that we know in modern people modulate behavior, they’re hardly affected at all. Selection in the last 10,000 years doesn’t seem to be focusing, on average, on cognitive and behavioral traits. It seems to be focusing on immune and cardiometabolic traits, on average, with exceptions. On average, there’s an extreme over representation of cardio metabolic traits. (Patel, 2024, 00:55:18)

Sasha Gusev (a cancer researcher and social activist) has cited this quote to argue that David Reich didn’t mean what he seemed to mean in his recent paper (Gusev, 2025). What, then, did he mean? The Reich Lab paper has a paragraph that closely matches the above quote.

… signals of selection are unusually associated with specific classes of traits. In particular, we find enrichment for SNPs contributing to blood-immune-inflammatory traits, compared to random SNPs with matched characteristics defining the baseline of 1-fold. In contrast, for mental-psychiatric-nervous and behavioral traits, we do not see enrichment. These patterns cannot be explained by differences in allele frequencies or purifying selection since we control for these factors. The intensity of selection on blood-immune-inflammatory and cardio-metabolic traits increased in the Bronze Age relative to the pre-farming period, which may reflect adaptation to new diets, higher population densities, or living closer to domesticated animals. (Akbari et al., 2024, p. 4)

In the appendix, Figure 1 has two aggregate categories “Mental-psychiatric-nervous” and “Behavioral”, each of which encompasses 13 traits. Presumably, the first category includes the 3 measures of cognitive ability, with the 10 others being Qualifications none, Schizophrenia, Reaction time, Bipolar disorder, Tobacco use disorder, Mental disorders related to tobacco, Noncognitive aspects of educational attainment, Qualifications A levels, Neuroticism and Depressive symptoms (Extended Data Figure 7; Extended Data Figure 13). Such a vast category would not provide a clear signal of selection, since many of these traits are independent of each other, and some are inversely correlated with each other. For instance, schizophrenia is inversely correlated with cognitive ability.

Perhaps Reich initially thought he had evidence for rapid cognitive evolution but then changed his mind. This, too, is unlikely. Patel interviewed him a month before the release of the Reich Lab paper.

More likely, Reich had seen an earlier version of the paper when he met Patel — a version that did not yet include the separate analyses of cognitive ability. In fact, in the interview transcript, he talks about these analyses as if they were still ongoing:

You might expect that in reaction to a change so economically, dietarily, cognitively transformative as agriculture, the genome might shift in terms of how it adapts. You might actually see that in terms of adaptation on the genome. You might expect to see a quickening of natural selection or a change. I don’t think we know the answer yet to whether that’s occurred, although they’re beginning to be hints. We could learn that from the DNA data. (Patel, 2024, 00:50:44)

What next?

In tropical regions, research will be hindered by the poor preservation of DNA in human remains. Complete or near-complete retrieval of ancient DNA is necessary for the study of cognitive evolution over time.

Nonetheless, we will soon see a study of cognitive evolution in South Asia. Its findings will probably resemble those of East Asia and the Roman world: a steady rise in mean cognitive ability, followed by decline. Cognitive evolution is usually driven by the higher fertility of elite individuals, and such people inevitably reach a level of development where the pursuit of wealth and power becomes severed from reproductive success.

Hopefully, we will see more studies of European cognitive evolution, particularly for the key period of late medieval and post-medieval times. During this period, mean cognitive ability rose steadily, perhaps beginning to rise earlier in England, Holland, and northern Italy. By charting this advance by region and by century, we may learn more about the historical processes leading to the Reformation, the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.

In the case of East Asia, we should closely examine the evolutionary trend of the last 1,500 years. Did mean cognitive ability simply stop rising? Or did it actually decline? In addition, did China and Japan differ in their trajectories of cognitive evolution?

Finally, future studies ought to control genomic data for socioeconomic status (SES). Otherwise, there may be sampling bias. Since the remains of elite individuals are more likely to survive the passage of time, their DNA should be overrepresented in older samples. Cognitive ability would thus seem to decrease over time. Of course, we generally see the opposite: an increase in cognitive ability over time. So there may have been even more cognitive evolution than what current studies suggest.

In any case, we can and should control for the SES of those deceased individuals who provide DNA. Often, it is already known. If not, it can be inferred through isotope analysis of the bones and teeth. High SES is associated with an ample, high-meat diet, and low SES with coarse grains and malnutrition.

References

Akbari, A., Barton, A.R., Gazal, S., Li, Z., Kariminejad, M., Perry, A., Zeng, Y., Mittnik, A., Patterson, N., Mah, M., Zhou, X., Price, A.L., Lander, E.S., Pinhasi, R., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., & Reich, D. (2024). Pervasive findings of directional selection realize the promise of ancient DNA to elucidate human adaptation. bioRxiv. September 15 https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.14.613021

Chen, T. T., Kim, J., Lam, M., Chuang, Y. F., Chiu, Y. L., Lin, S. C., ... & Won, H. H. (2024). Shared genetic architectures of educational attainment in East Asian and European populations. Nature Human Behaviour, 8(3), 562-575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01781-9

Frost, P. (2011). East Asian intelligence, Evo and Proud, February 18. https://evoandproud.blogspot.com/2011/02/east-asian-intelligence.html

Frost, P. (2024a). Cognitive evolution in Europe: Two new studies. Peter Frost’s Newsletter, March 14. https://www.anthro1.net/p/cognitive-evolution-in-europe-two

Frost, P. (2024b). How Christianity rebooted cognitive evolution, Aporia Magazine, October 10.

Frost, P. (2025a). Cognitive evolution in eastern Eurasia, Aporia Magazine, February 8.

Frost, P. (2025b). The Great Cognitive Advance, Aporia Magazine, July 31.

Gusev, S. (2025). https://x.com/SashaGusevPosts/status/1932649103898366243

Hawks, J. (2023). Did two pulses of evolution supercharge human cognition? John Hawks Weblog, May 15. https://johnhawks.net/weblog/did-two-pulses-of-evolution-supercharge-human-cognition/

Hawks, J., Wang, E. T., Cochran, G. M., Harpending, H. C., & Moyzis, R. K. (2007). Recent acceleration of human adaptive evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), 104, 20753-20758. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707650104

Kuijpers, Y., Domínguez-Andrés, J., Bakker, O.B., Gupta, M.K., Grasshoff, M., Xu, C.J., Joosten, L.A.B., Bertranpetit, J., Netea, M.G., & Li, Y. (2022). Evolutionary Trajectories of Complex Traits in European Populations of Modern Humans. Frontiers in Genetics, 13, 833190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.833190

Libedinsky, I., Wei, Y., de Leeuw, C., Rilling, J. K., Posthuma, D., & van den Heuvel, M. P. (2025). The emergence of genetic variants linked to brain and cognitive traits in human evolution. Cerebral Cortex, 35(8), bhaf127. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaf127

Patel, D. (2024). David Reich – How one small tribe conquered the world 70,000 years ago. Dwarkesh Podcast, August 29.

Piffer, D. (2025a). Directional Selection and Evolution of Polygenic Traits in Eastern Eurasia: Insights from Ancient DNA. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 28(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2024.49

Piffer, D. (2025b). The genetic evolution of the human race and its consequences for the Industrial Revolution, November 17, PifferPilfer.

Piffer, D., & Connor, G. (2025a). Genomic Evidence for Clark’s Theory of the British Industrial Revolution, preprint, ResearchGate, June. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392808200_Genomic_Evidence_for_Clark’s_Theory_of_the_British_Industrial_Revolution

Piffer, D., & Connor, G. (2025b). Genomic Evidence for Clark’s Theory of the Industrial Revolution, preprint, ResearchGate, November. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392808200_Genomic_evidence_for_Clark’s_theory_of_the_Industrial_Revolution

Piffer D, Dutton, E., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2023). Intelligence Trends in Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of Roman Polygenic Scores. OpenPsych, July 21, 2023. https://doi.org/10.26775/OP.2023.07.21

Piffer, D., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2024). Evolutionary Trends of Polygenic Scores in European Populations from the Paleolithic to Modern Times. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 27(1), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2024.8

Wen, F., Wang, E. H., & Hout, M. (2024). Social mobility in the Tang Dynasty as the Imperial Examination rose and aristocratic family pedigree declined, 618–907 CE. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(4), e2305564121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2305564121

Not at all convincing, for one very simple reason each generation of Western Europeans for at least the last 50 years have been increasingly stupid and useless driven by the increasing shallowness of the culture.

Any theory which extrapolates mental and emotional characteristics based solely on genetics is at best a very partial view and takes no account of cultural influences which are at least as important to human development , if not more so ( and there is a lot of evidence for the latter).

This evidence doesn’t exist at cellular level , unlikely these nerds would get their vision above the level of their electron microscopes though, as they completely lack contextual intelligence.

Classic Maya remains are going to be quite interesting. I wonder what the genotypic profile of those Mayas will look like. They developed a fully fleshed-out writing system and appear to have had an advanced astronomical tradition. The most direct indication of high intelligence is that they sustained a very high population density in the Maya lowlands (possibly as many as 16 million people at their peak!). Of course, while they hold no candle to the Ancient Greeks, it should also be taken into account that they achieved all of this in a far less dynamic environment, with limited external influences or predecessors beyond other surrounding Mesoamerican cultures. What might their solution to the large society problem have looked like? Their decline seems particularly severe as well, with extreme depopulation in the Maya lowlands (up to 90% in some areas, apparently) by the end of the Classic era and a reduction in the complexity of their writing system.