Reply to Joseph Henrich

When did northwest Europeans become WEIRD?

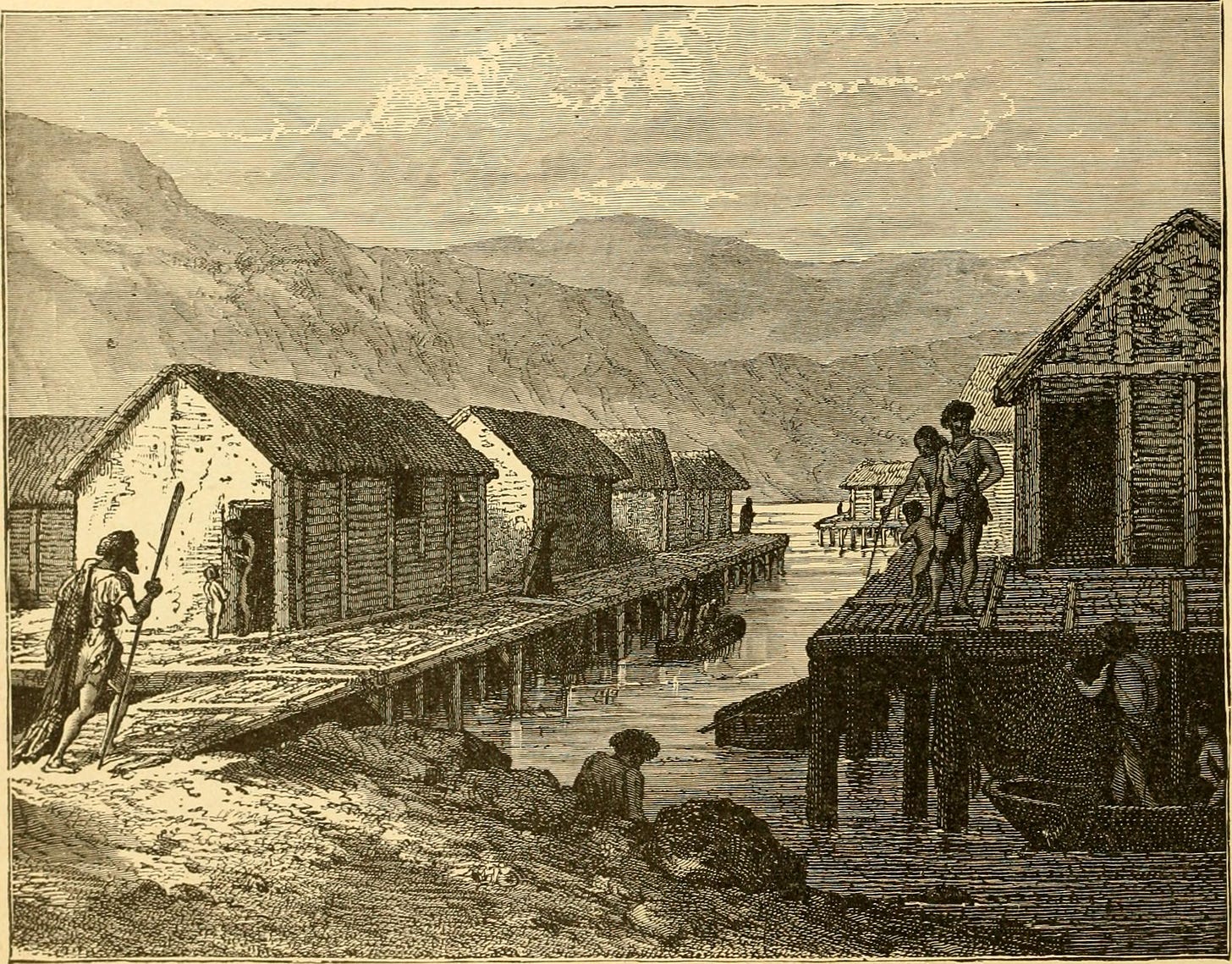

An early fishing village in Europe (Ridpath’s History of the World - Wikicommons)

How did northwest Europeans become more individualistic, less clannish, and more adept at impersonal prosociality? Was it because of the Western Church’s restrictions on cousin marriage and polygyny? Or did Christianity adopt these norms as it spread into Europe?

What does aDNA tell us about northwest Europeans before they became Christian? Was their individualism due to Western Christianity and its restrictions on cousin marriage and polygyny? Or did these norms already exist as Christianity spread north and west into Europe?

Also, how do the elements of this behavioral package relate to each other? Did a certain marriage pattern lead to individualism? Or did both have a common cause?

These are the questions I tried to address in my last post, which was first published in Aporia Magazine. My reposting led to another round of criticism from Joseph Henrich on X. His criticisms and my responses are given below in the hope that debate will bring both of us closer to the truth.

First, the work referenced by my colleagues and I is about kinship intensity, only one element of which involves cousin marriage. It's quite possible to have low rate of cousin marriage but high kinship intensity. This is a fundamental misreading.

In your landmark paper in Nature, you argued that the Christian bans on polygyny and cousin marriage reduced kinship intensity and thereby promoted individualism. Kinship intensity was thus lower in Western Europe because the Western Church imposed a more radical ban on cousin marriage:

Crucially, while the Eastern Church did adopt some of the same policies as the Western Church, it never endorsed the Western Church’s extensive prohibitions on cousin marriage, adopted many policies only later, and was unenthusiastic about enforcement. Thus, we expect similar but substantially weaker effects for the Eastern Church. Other sects of Christianity adopted even less of the MFP [marriage and family policy]. Nestorian and Coptic Christians, for example, continued marrying their cousins for at least another millennium. (Schulz et al., 2019, p. 10)

You define the “kinship intensity index (KII)” as follows:

The KII is an omnibus measure for kinship intensity that captures the presence of cousin-marriage preferences, polygamy, co-residence of extended families, clan organization, and community endogamy. (Schulz et al., 2019, p. 3)

Let’s assume that these elements are not listed in order of importance. Let’s also assume that cousin marriage has a minor influence on the KII. What do we know about the other elements when the Western Church was still working out its marriage and family policy? Was the KII higher then than it is today?

In Carolingian Gaul at a time of increasing population on the estates of the Abbey of St Germain-des-Prés near Paris about 801-20 some 4,316 married or once-married adults had 4060 children. Households were nuclear and small amongst the married folk — rather under four persons on average — and, in addition, there were about 843 single adults, mostly men. About 16.3 per cent of the adult population were unmarried, so that in many respects there was already a Western European marriage pattern.

… During the ninth century the situation in Villeneuve-Saint-Georges was similar. The now or ever-married adults constituted 47.9 per cent of the entire population and the children 46.6 per cent. Households mainly consisted of parents and children. Seven children lived with their father only, and 15 with their mother. Only 22 parents lived with their son and twelve unmarried sons with their parents. Four widowers, four widows, nine bachelors and five spinsters seem to have lived alone. Of the adult population 11.5 per cent had never married. The picture is very like that of Western Europe in modern times. (Hallam, 1985, p. 56)

So even in the early ninth century, when the Western Church had not yet adopted its most radical policies on marriage and family, we already see a familiar picture of nuclear families, as well as high rates of adults living alone.

Second, proper quantitative reanalyses of historical data, such as epigraphies, suggest lots of cousin marriages in the Roman Empire. Our team of classists is using the same approaches as past historians except we rely on more extensive datasets.

According to aDNA from a wide range of regions and time periods, cousin marriage was rare during the Roman period and during Antiquity in general:

We found that only 1 out of 1785 ancient individuals have long ROH typical for the offspring of first-degree relatives (e.g., brother–sister or parent–offspring). Historically, matings of first-degree relatives are only documented in royal families of ancient Egypt, Inca, and pre-contact Hawaii, where they were sporadic occurrences7. The only other example of an offspring of first-degree relatives found using aDNA to date is the recently reported case from an elite grave in Neolithic Ireland. Our findings are in agreement that first-degree unions were generally rare in the human past (Ringbauer et al., 2021).

Cousin marriage seems to have become common only in later times, possibly during the Islamic period.

… In two specific regions with high levels of long ROH in the present-day2, the dataset contained a sufficient number of ancient individuals to allow analyzing time transects. For both transects (the Levant and present-day Northwest Pakistan), we observe a substantial shift in the levels of long ROH. In contrast to the high abundance of long ROH typical of close kin unions in the present-day individuals, long ROH was uncommon in the ancient individuals, including up to the Middle Ages. (Ringbauer et al., 2021)

Even if we assume that cousin marriage became common as early as Roman times, we cannot assume that the same change in marriage patterns affected the non-Romanized and semi-Romanized populations of northwest Europe.

Third, the ancient DNA paper referenced was done by a post-doc in the lab next door to my office. Harold's method only distinguishes 1st cousin marriages with any confidence, not more distant pairings. Most cousins are more distant; Church also banned spirit kin and affines.

I referenced four different papers, which used different methods.

Gnecchi-Ruscone et al. (2024) used two methods:

KIN (Kinship INference), which can confidently identify first- and second-degree relationships;

ancIBD, which can detect close genetic relationships up to the sixth degree.

They found evidence of only one possible marriage between first cousins out of around 300 individuals, and no evidence of cousin marriage at higher degrees. Admittedly, this study used aDNA from Avars and may thus be irrelevant to the issue of marriage patterns among indigenous northwest Europeans.

Wang et al. (2025) likewise used KIN and ancIBD. They examined aDNA from two sites in Austria: a non-Avar one (Mödling, or MGS) and an Avar one (Leobersdorf, or LEO). They concluded:

Given that none of the newly reported individuals carry high amounts of runs-of-homozygosity genomic regions—the indication of inbreeding—as estimated by hapROH … we infer that consanguinity was strictly avoided in both MGS and LEO across six generations. That was mainly achieved by exogamy: 17 of the 19 (90%) mothers buried in Leobersdorf with identifiable offspring have no ancestors buried on site; in the much larger community of Mödling, they are 46 out of 59 (78%). Many daughters seem to have left to be married elsewhere; between ages 7 and 17 years, the sex ratios of the deceased male to female individuals at LEO and MGS are about 1.5:1 and 1.7:1 respectively, and among adults, hardly any female individuals born by parents on site remain.

Blöcher et al. (2025) used the ancIBD method. They concluded:

The near absence of long (>12 cM) runs of homozygosity (ROH) and the lack of shared IBD segments (>8 cM) between spouses support strict incest avoidance, excluding relationships closer than the sixth degree.

Cassidy et al. (2025) used a method called ped-sim, which is accurate up to the fourth degree of relatedness (Caballero et al., 2019). They concluded:

Y chromosome diversity is high …, and patterns of ROH imply that these were relatively large outbreeding communities.

Furthermore, many cousins were 'half cousins' because of polygyny--our fathers were half brothers (different moms). Or, our grandfathers were half brothers. The aDNA method has little resolution for this.

Polygyny was common only among the Avars, a Turkic people who lived in Austria and Hungary at that time. It was rare within pre-Christian indigenous populations elsewhere in northwest Europe:

England – no mention of polygyny (Cassidy et al., 2025).

Southern Germany –

In Altheim and Büttelborn, five individuals (four men and one woman) had multiple partners, though it remains unclear whether this reflects polygamy or serial monogamy. Nonetheless, the predominance of 61 single-partner unions suggests that monogamy was the norm in Early Medieval southern Germany (Blocher et al., 2025).

Austria (Avars and indigenous Europeans) – polygyny is attested at the Avar site. At the non-Avar site, multi-reproductive unions seem to be levirate marriages.

At Mödling, female individuals also had children with two or more partners almost as often as male individuals (15 out of 31). As most partners of these multi-reproductive female individuals were related to each other (brothers, half-brothers, stepsons), these were probably levirate unions, an arrangement under which a widow marries a male relative of her deceased partner. (Wang et al., 2025).

Hungary (Avars) –

In RK only, we discovered 15 cases involving a male partner and 7 cases involving a female one. Male individuals had two partners in ten cases, three partners in four cases, and four partners in one case (RKF042); around 85% of these individuals are older men (aged 35–59). The young ages of female partners at death may indicate serial monogamy (RKC011), but the presence of older female partners in multiple partnerships suggest polygyny (RKF042 and RKF180). Multiple reproductive partners were also discovered in HNJ and KFJ (one and four cases, respectively). That means that polygyny might not have been restricted to the highest stratum of society that is known from the historical sources, but also occurred in the general population (Gnecchi-Ruscone et al., 2024).

Fourth, we have been compiling all the studies of the ancient DNA from European burials. Taken together, they provide strong support for intensive kinship, including clans, extended families, patrilineal inheritance and polygyny. So, Cherry picking...

The term “cherry picking” implies that I ignored some of the relevant aDNA studies. Actually, I did miss two when I wrote my last post, one concerning Europe in general and the other concerning Ireland. Both seem in line with the other studies, particularly with respect to low rates of polygyny and cousin marriage since the Neolithic transition:

In fact, several Neolithic burials show evidence of nuclear families, which may reflect a monogamous marriage system. A shift from polygyny to monogamy would have the effect of decreasing male variance in reproductive success, since more males would now be able to mate, and consequently would increase Nm. This could result in a signal of population growth in NRY data that would be more recent compared to that observed in mtDNA and is exactly what Dupanloup and colleagues have argued and found. Our results are in good agreement with theirs. (Rasteiro & Chikhi, 2013)

Importantly, where multiple genomes have been sequenced from Neolithic contexts in Ireland, studies have shown that most of the individuals buried together were not closely biologically. This contrasts strongly with the findings from the well-preserved burial deposits of Frälsegården or Hazleton, but matches the general picture emerging from Britain, including Orcadian passage tombs (with their admittedly small sample sets), of people buried together not being closely related, especially in the Later Neolithic. Where such inter- or intra-site relations have been identified from Ireland, they are frequently distant (e.g. fifth degree or further: e.g. second cousins or a great-great-great grandparent), rather than close genetic relationships (e.g. first to fourth degree: parents, children, siblings, grandparents/grandchildren, uncles or aunts or nieces and nephews, or first cousins). (Carlin et al., 2025)

Fifth, the study referenced in PLoS One, which supposedly undermines our approach, actually supports it. The analysis is riddled with problems. We'll be providing a proper reanalysis.

We are preparing a full-throated reply, which we'll publish in an actual journal instead of blogging. This thread is so replete with errors, misstatements and misreadings, it's difficult to know where to begin. I will hold most of my comments for that forum. Nevertheless...

I await your paper. I hope it will cover all of the aDNA studies of pre-Christian northwest Europeans.

Discussion

We all can become invested in our ideas, myself included. It’s important, however, to revise our ideas when they’re proven wrong. Perhaps that point has not been reached in this debate. Perhaps avoidance of cousin marriage is irrelevant. It may just be a general North Eurasian adaptation, as indicated by the Avar aDNA. On the other hand, a low polygyny rate seems to be much more specific to northwest Europeans, and it likewise seems to precede Christianization.

Hopefully, aDNA will be examined for other heritable WEIRD traits, such as impersonal prosociality, affective empathy, and guilt proneness. But such research will be conducted only if it seems justified. Hence the importance of debate on the origins of WEIRDness.

If WEIRDness didn’t begin with Christianity, when and how did it? HBD*chick has argued that it began with the spread of manorialism in the early Middle Ages (HBD*chick, 2012). This explanation has its share of problems:

Manorialism didn’t take off in northwest Europe until the seventh to eighth centuries, so we still have to explain the low rates of polygyny and cousin marriage in earlier times.

Even if we assume that WEIRDness is an outcome of purely cultural evolution — with no genetic changes — we still have to explain why the inhabitants of French manors were already fully WEIRD at the beginning of the ninth century. Is such a fundamental cultural shift possible over such a short time interval?

Finally, feudal India had a similar system of land tenure. Why didn’t WEIRDness evolve there?

I’m inclined to see WEIRDness as being much older. To me, it looks like an adaptation to the fluid social environment that prevailed around the North Sea and the Baltic in the Late Mesolithic. These coastal peoples spent the winter inland, as small hunting bands of closely related individuals. In the summer, they congregated in large coastal settlements to subsist on fishing and sealing. They thus had to live at close quarters with non-kin, and not necessarily the same ones in each successive year. Such an environment may have selected for WEIRDness, especially weaker kinship ties and impersonal prosociality (Frost, 2020).

I may be wrong. And I always have to live with that possibility.

References

Blöcher, J., Vallini, L., Velte, M., Eckel, R., Guyon, L., Winkelbach, L., … Burger, J. (2025). Historic Genomes Uncover Demographic Shifts and Kinship Structures in Post-Roman Central Europe. bioRxiv, 2025.03.01.640862; https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.03.01.640862

Caballero, M., Seidman, D.N., Qiao, Y., Sannerud, J., Dyer, T.D., Lehman, D.M., et al. (2019) Crossover interference and sex-specific genetic maps shape identical by descent sharing in close relatives. PLoS Genet, 15(12): e1007979. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007979

Carlin, N., Smyth, J., Frieman, C. J., Hofmann, D., Bickle, P., Cleary, K., ... & Pope, R. (2025). Social and genetic relations in Neolithic Ireland: re-evaluating kinship. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774325000058

Cassidy, L. M., Russell, M., Smith, M., Delbarre, G., Cheetham, P., Manley, H., ... & Bradley, D. G. (2025). Continental influx and pervasive matrilocality in Iron Age Britain. Nature, 637(8048), 1136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08409-6

Frost, P. (2020). The large society problem in Northwest Europe and East Asia. Advances in Anthropology, 10(3), 214-234. https://doi.org/10.4236/aa.2020.103012

Gnecchi-Ruscone, G. A., Rácz, Z., Samu, L., Szeniczey, T., Faragó, N., Knipper, C., ... & Hofmanová, Z. (2024). Network of large pedigrees reveals social practices of Avar communities. Nature, 629(8011), 376-383. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07312-4

Hallam, H.E. (1985). Age at First Marriage and Age at Death in the Lincolnshire Fenland, 1252-1478. Population Studies, 39, 55-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000141276

HBD*chick. (2012). Medieval manorialism and the Hajnal line. HBD*chick, June 2. https://hbdchick.wordpress.com/2012/02/06/medieval-manoralism-and-the-hajnal-line/

Rasteiro, R., & Chikhi, L. (2013). Female and Male Perspectives on the Neolithic Transition in Europe: Clues from Ancient and Modern Genetic Data. PLoS ONE, 8(4): e60944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060944

Ringbauer, H., Novembre, J., & Steinrücken, M. (2021). Parental relatedness through time revealed by runs of homozygosity in ancient DNA. Nature Communications, 12, 5425. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25289-w

Schulz, J.F., Bahrami-Rad, D., Beauchamp, J.P., & Henrich, J. (2019). The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation. Science, 366(707), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau5141

Wang, K., Tobias, B., Pany-Kucera, D., Berner, M., Eggers, S., Gnecchi-Ruscone, G. A., ... & Hofmanová, Z. (2025). Ancient DNA reveals reproductive barrier despite shared Avar-period culture. Nature, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08418-5

This paragraph is confusing:

"First, the work referenced by my colleagues and I is about kinship intensity, only one element of which involves cousin marriage. It's quite possible to have low rate of cousin marriage but high kinship intensity. This is a fundamental misreading."

Is is "quite possible" or is it a "fundamental misreading"?

Likely even older because what your potted societal profile describes is found in egalitarian H&G life in bands (including non-related kin). What you describe is then an potentially available substrate of worlding. As such it is then a substrate that "cultural evolution" diverges from (continually). If we accept the ideas of the egalitarian revolution of the paleolithic, as a deeply human feature or option, and so, as a continually available strange attractor, defines our success as Homo sp. generally. Individual focus is always an option. (admittedly WEIRDness is a suite of features).

Narcissistic baboons don't like this of course.

Also, might be better to call it history rather than "cultural evolution". That word evolution is too loaded. Repeating it mantra like is perhaps too defensive. (And if we can accept societies as 'records' of themselves in a taphonomical like study then history is a good term.)

What makes WEIRD weird is creating a "social institution" of the individual (in recent historical times). This is also a divergence from the substrate, but this time doubling-down on the feature of individual-ness that is otherwise assumed in an egalitarian perspective, and so not necessarily celebrated in a society's 'high' or professed culture. I.E. you can be egalitarian (behave egalitarian-ly or expect it) without the notice of the 'individual' as part of a group's worlding of selves (kulcha).

(Of course if one has authoritarian impulses this egalitarian option can be felt as an attack on one's freedom to punch down or enslave others).

https://whyweshould.substack.com/p/reading-joseph-henrich-two-social

______________________________

(Also as I am travelling) I cannot find a recent DNA paper that posits (from memory) Germanic speakers' (indo-hybridty's) origin near the Gulf of Bothnia (that coastal area of what is now Finland & Russia, including where Swedes moved into later and which Finns 'never really moved into'). Then they stayed coastal, exploited fish and seals through the Baltic. BTW the word soul is the word seal. Totemic? (and makes much more sense of Gotland as a seaway heartland) All well prior to the Nordic Bronze age.