Are human populations 99.9% identical?

A correct finding wrongly interpreted

Head of a chimpanzee, Edward Lear, 1835 - Humans and chimps are supposed to be 98-99% genetically identical. Why, then, are they so different?

In their genes, humans and chimpanzees are 98-99% the same and human populations 99.9% the same. Two geneticists made this finding a half-century ago, yet they actually didn’t. In fact, they warned against such misinterpretation.

You’ve probably heard that humans and chimpanzees are genetically 98 to 99% the same and human populations 99.9% the same. Both findings are often mentioned. In a speech to high school graduates, Hillary Clinton “cited genetic research that shows humans are 99.9 percent the same.”

"The differences in how we look — in our skin color, our eye color, our height — stem from just one-tenth of 1 percent of our genes. And the differences among us — our cultures, our religious beliefs, the music we like — it is all so small a distinction in our sea of common humanity," she said. (Hawks, 2007)

Of course, one tenth of one percent is still a lot. As anthropologist John Hawks pointed out, “one-tenth of 1 percent of 3 billion is a heck of a large number — 3 million nucleotide differences between two random genomes.”

He added:

We differ by one-tenth of 1 percent of nucleotides, this is enough to make coding differences in a large fraction of our genes. (Hawks, 2007).

In other words, the 0.1% difference doesn’t refer to genes. It refers to nucleotides. A single gene is a long chain of nucleotides, often a very long one, and a single nucleotide mutation can alter how the entire chain works. Conceivably, each and every gene could differ by 0.1% among human populations, and each and every one could work differently in different people.

Genes also differ in how their chains of nucleotides are arranged. The same chain may be repeated consecutively or copied and inserted somewhere else. Such rearrangements are more important than nucleotide changes in altering how a gene works: “Structural variations, such as copy-number variation and deletions, inversions, insertions and duplications, account for much more human genetic variation than single nucleotide diversity” (Wikipedia, 2025).

How, then, can we measure the genetic distance between two groups in terms of real functional differences? One way is to look at what genes make, namely proteins. Whereas humans and chimpanzees are 98-99% the same in their nucleotides, they are only 20% the same in their proteins (Glazko et al., 2005).

But the biggest functional difference is not so much in the proteins themselves as in the way they are used to build living tissues, notably in the brain (Yoo et al., 2025). Living tissue is created by a tiny minority of genes that regulate how other genes are expressed, often thousands of others. Although these “regulator genes” are much fewer in number than other genes, they are far greater in their effects, particularly on growth and development.

The source of a legend

A half-century ago, two researchers — Mary-Claire King and Allan Wilson — discovered that humans and chimpanzees differ the most in “regulator genes.” They wrote up their finding in a landmark paper, and it is here that we first see the estimates of 98-99% and 99.9% sameness. The two authors argued that the higher primates had evolved mainly through changes at a tiny fraction of all genes:

The molecular similarity between chimpanzees and humans is extraordinary because they differ far more than sibling species in anatomy and way of life. … Because of these major differences in anatomy and way of life, biologists place the two species not just in separate genera but in separate families.

… small differences in the time of activation or in the level of activity of a single gene could in principle influence considerably the systems controlling embryonic development. The organismal differences between chimpanzees and humans would then result chiefly from genetic changes in a few regulatory systems, while amino acid substitutions in general would rarely be a key factor in major adaptive shifts. (King & Wilson, 1975, pp. 113-114)

The two researchers were thinking not only about the human-chimpanzee difference but also about the differences among human populations:

This [human-chimpanzee] distance is 25 to 60 times greater than the genetic distance between human races. In fact, the genetic distance between Caucasian, Black African, and Japanese populations is less than or equal to that between morphologically and behaviorally identical populations of other species. (King & Wilson, 1975, p. 113)

The above paragraph is within a longer discussion about the paradoxical smallness of the human-chimpanzee genetic distance. In fact, the paradox is spelled out in the next paragraph:

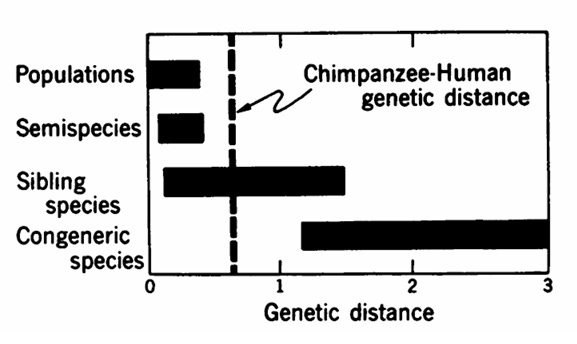

However, with respect to genetic distances between species, the human-chimpanzee D value is extraordinarily small, corresponding to the genetic distance between sibling species of Drosophila or mammals. Nonsibling species within a genus … generally differ more from each other, by electrophoretic criteria, than humans and chimpanzees. The genetic distances among species from different genera are considerably larger than the human-chimpanzee genetic distance. (King & Wilson, 1975, p. 113)

Genetic distance between humans and chimpanzees, compared to genetic distances in other taxa. (King & Wilson, 1975, p. 113)

So, again, how can we measure the genetic distance between two groups in terms of real functional differences? In the case of human populations, there is no easy answer because few species have had a similar evolutionary history. We evolved rapidly at the very time we were splitting up and adapting to different environments — not only natural environments from the equator to the arctic but also an ever-wider range of cultural environments. In fact, this acceleration of human adaptation to new environments largely explains the concurrent acceleration of human evolution (Akbari et al., 2024; Cochran & Harpending, 2009; Frost, 2023a; Hawks et al., 2007; Kuijpers, et al., 2022; Libedinsky et al., 2025; Piffer & Kirkegaard, 2024; Rinaldi, 2017).

Because natural selection has shaped our species in highly divergent ways, it has contributed much more to diversity between populations than to diversity within them. The second kind of diversity is due mostly to stochastic processes of little adaptive consequence, since everyone is adapting to the same environment and the same selection pressures. Within a population, natural selection creates diversity only in a few cases, essentially through frequency-dependent selection and disruptive selection.

We come again to the same paradox. If we calculate the ratio of between-population diversity to total diversity, i.e., the Fst, we get a low ratio even though human populations differ much more anatomically than do most sibling species in the animal kingdom.

As Charles Darwin noted, a naturalist would consider some human groups to be “as good species as many to which he had been in the habit of affixing specific names.” This is true because genetic diversity is much more consequential between human populations than within them. Fst is therefore an apples-to-oranges comparison (Darwin, 1936 [1888], pp. 530-531; Frost, 2023b).

Discussion

I don’t blame Hillary Clinton for drawing the wrong conclusion from the 99.9% estimate, but I’m less forgiving toward those who have silently gone along with it while knowing better. John Hawks knew better and did not silently go along when he criticized Hillary’s speech in one of his posts. That post remained on his website until he deleted it in 2021 — after he apparently got the memo that Hillary was right.

“Nice research lab you have there. Pity if anything happened to it.”

When academics choose the path of silence, and withhold their objections, they help create a fake consensus that ultimately brings academia into disrepute.

References

Akbari, A., Barton, A.R., Gazal, S., Li, Z., Kariminejad, M., Perry, A., Zeng, Y., Mittnik, A., Patterson, N., Mah, M., Zhou, X., Price, A.L., Lander, E.S., Pinhasi, R., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., & Reich, D. (2024). Pervasive findings of directional selection realize the promise of ancient DNA to elucidate human adaptation. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.14.613021

Anon. (2007). Finding said to show "race isn't real" scrapped http://www.world-science.net/othernews/070904_human-variation.htm

Cochran, G. & Harpending, H. (2009). The 10,000 Year Explosion: How Civilization Accelerated Human Evolution. Basic Books: New York. https://www.amazon.ca/000-Year-Explosion-Civilization-Accelerated/dp/0465002218

Darwin, C. (1936 [1888]). The Descent of Man and Selection in relation to Sex. reprint of 2nd edition, The Modern Library, New York: Random House.

Frost, P. (2023a). Human evolution didn’t slow down. It accelerated! Peter Frost’s Newsletter, July 12.

Frost, P. (2023b). Do human races exist? Peter Frost’s Newsletter. August 15.

Glazko, G., Veeramachaneni, V., Nei, M., & Makałowski, W. (2005). Eighty percent of proteins are different between humans and chimpanzees. Gene, 346, 215-219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2004.11.003

Hawks, J. (2007). Disagreeing with Hillary Clinton on human genetic differences. John Hawks Weblog https://web.archive.org/web/20210624221131/http://johnhawks.net/weblog/topics/race/differences/clinton_2007_proportion_differences_speech.html

Hawks, J., Wang, E. T., Cochran, G. M., Harpending, H. C., & Moyzis, R. K. (2007). Recent acceleration of human adaptive evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(52), 20753-20758. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707650104

King, M-C. & Wilson, A.C. (1975). Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees: Their macromolecules are so alike that regulatory mutations may account for their biological differences. Science, 188, 107-116. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1090005

Kuijpers, Y., Domínguez-Andrés, J., Bakker, O.B., Gupta, M.K., Grasshoff, M., Xu, C.J., Joosten, L.A.B., Bertranpetit, J., Netea, M.G., & Li, Y. (2022). Evolutionary Trajectories of Complex Traits in European Populations of Modern Humans. Frontiers in Genetics, 13, 833190. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.833190

Libedinsky, I., Wei, Y., de Leeuw, C., Rilling, J. K., Posthuma, D., & van den Heuvel, M. P. (2025). The emergence of genetic variants linked to brain and cognitive traits in human evolution. Cerebral Cortex, 35(8), bhaf127. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaf127

Piffer, D., & Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2024). Evolutionary Trends of Polygenic Scores in European Populations from the Paleolithic to Modern Times. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 27(1), 30-49. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2024.8

Redon, R., Ishikawa, S., Fitch, K. R., Feuk, L., Perry, G. H., Andrews, T. D., ... & Hurles, M. E. (2006). Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature, 444(7118), 444-454. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05329

Rinaldi, A. (2017). We’re on a road to nowhere. Culture and adaptation to the environment are driving human evolution, but the destination of this journey is unpredictable. EMBO reports 18: 2094-2100. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201745399

Wikipedia (2025). Human genetic variation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_genetic_variation

Yoo, D., Rhie, A., Hebbar, P., Antonacci, F., Logsdon, G. A., Solar, S. J., ... & Eichler, E. E. (2025). Complete sequencing of ape genomes. Nature, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08816-3

Always fascinating topics here and always just within my ability to understand, though written by almost anyone else they wouldn't be.

I think the last paragraph was meant as two cheers for John Hawks, though he didn't quite hold out for the whole three. Still, sounds like he was a damn sight braver than most of his peers, who folded without a fight.

When someone mentions the 99.9% thing I (mis)quote the bit from Steve Sailor’s book where he stayes that we are 67% genetically identical to phosphorescent mould, or something.